52 weeks. 52 different writers. 2 trade paperbacks or hardcovers a week. Each week I’ll take a look at a different writer and read two different collected editions from within that person’s repertoire to help in the examination of their work. Well here it is, the “grand finale” of this weekly challenge. The 52nd writer, and I most certainly saved the best for last. My girlfriend is still with me which is good considering I wasn’t so sure she’d want to stay with me when I started this challenge. Although, she is mildly upset with me for “working too much”. I didn’t even know there was such a thing as working too much but I’ve digressed enough at this point. So yeah, let’s get this show on the road.

Usually this is the part where I write some facts about the author I’m doing a post on. This week, the final week of the challenge I’ve embarked upon, is all about Alan Moore. He’s one of the most well-known, well-respected, and oddball comic creators ever. Alan Moore has written some of the most iconic and well-known comics to have been produced from this artistic medium, with even that choice of words failing to do him true justice for his impact on the comic book world. There is so much I could write just about Alan Moore (not even his work, just the man himself) that it’s actually a daunting task trying to bring together an appropriate opening paragraph for this post. Moore is a man who has been doing this for decades and it shows across his entire body of work.

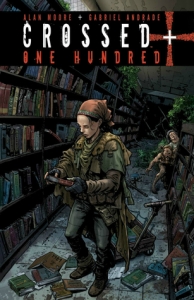

Crossed +100 Vol 1

One hundred years ago “The Surprise” occurred, an event where humans turned psychotic and began to inexplicably maim as well as defile each other, committing some of the most vile acts that a human mind could conceive. In the present day, these “infected” humans, easily denoted by a rash on their face that resembles an inverted cross, have began to dwindle in numbers, having once nearly overrun the Earth to now be outnumbered by the remaining, uninfected humans. Without an education system, government body, conventional modes of transportation, and several other staples of the regular lives we lead, the world has dramatically evolved into something familiar yet still wildly different. The English language has degraded, being a sorry mixture of casual and slang words with our common tongue to give a type of speaking that resembles that of a four-year old but with more expletives that equate to meanings you wouldn’t think of. In the midst of this changing world is a young woman named Future Taylor, an archivist who travels with her group to explore the world and gather information on how life used to be. Operating out of the large settlement of Chooga, this group of explorers becomes dismayed when they encounter a group of “infected”, an uncommon sight in the year 2108. Following several other encounters with these “infected”, Future Taylor begins to worry that a larger plot is at hand involving these tainted humans. But is Future too late to stop these dangers that are already unfolding around her?

One hundred years ago “The Surprise” occurred, an event where humans turned psychotic and began to inexplicably maim as well as defile each other, committing some of the most vile acts that a human mind could conceive. In the present day, these “infected” humans, easily denoted by a rash on their face that resembles an inverted cross, have began to dwindle in numbers, having once nearly overrun the Earth to now be outnumbered by the remaining, uninfected humans. Without an education system, government body, conventional modes of transportation, and several other staples of the regular lives we lead, the world has dramatically evolved into something familiar yet still wildly different. The English language has degraded, being a sorry mixture of casual and slang words with our common tongue to give a type of speaking that resembles that of a four-year old but with more expletives that equate to meanings you wouldn’t think of. In the midst of this changing world is a young woman named Future Taylor, an archivist who travels with her group to explore the world and gather information on how life used to be. Operating out of the large settlement of Chooga, this group of explorers becomes dismayed when they encounter a group of “infected”, an uncommon sight in the year 2108. Following several other encounters with these “infected”, Future Taylor begins to worry that a larger plot is at hand involving these tainted humans. But is Future too late to stop these dangers that are already unfolding around her?

Alan Moore gives his best shot at building a fascinating future civilization around the concept that drives this fan favourite horror series in Crossed +100. Moore shows the reader what the world would be like one hundred years from now if civilization nearly collapsed following the unexplained outbreak of insanity in the human race, leading a vast majority of the human population to commit deplorable acts of rape, murder, cannibalism, and much more. One hundred years without school, electricity, proper transportation, and many other staples of life is shown to have taken its toll on the human race. But, much like the history that lies before us, the threat of the infected eventually subsides, with the battle for survival shifting to become a battle for rebirth. As years pass, age catches up with everyone and everything, including the infected humans. As a result, the population of the infected that once outnumbered your healthy humans begins to decrease as elements like food, age, and slaughtering their offsprings due to their psychotic nature all result in their inability to build a foundation for a new civilization.

The world building that Alan Moore does for Crossed +100 is highly interesting because of the different layers he adds to what he is doing. Alan Moore does more than just examine how the world would change in a geographical sense due to the outbreak of this specific type of infected and does all his world building in the truest sense as he literally makes an entirely new Earth from which these characters live off of. Without a school system in place, the language that these characters use changes in a way that makes them all sound highly uneducated and come off as human beings in the most basic sense. Travel by conventional means like cars is all but forgotten. Cities and towns are now a thing of the past as humans have developed new settlements and strongholds in favour of creating more secure locations.

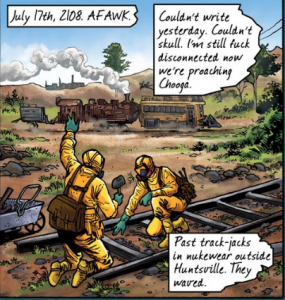

The most interesting degree to Moore’s vision is how he changes language, taking words that are common to us and giving them a whole new meaning. For example, instead of a character saying something like “I thought about that!” they would say something like “I skulled it!”, with the idea being that using one’s head is part of the action used when it comes to thinking so somewhere along the line the word “think” is completely abandoned in place of the term “skull”. Other examples like the use of the words “and but” in conjunction with each other show that sentence structure was damaged somewhere in the midst of the past one hundred years as the use of the word “and” in that instance is unnecessary as “and but” together in Moore’s world translates plainly to “but”. The way words are used here is fascinating because it’s meant to be oversimplified to imply to the reader that language has taken a step back towards something like that of the Neanderthals but then the overuse of some words shows that logic is still there, it’s just misplaced. Another interesting decision Moore makes with his language structure is the emphasis on curse words, having some of them become more common than the word “the”. Moore uses the “f-word” in such a casual way that it actually has multiple meanings on top of its standard meaning that we’ve become used to. Other words like “brown/browned” have foul meanings as well, that you can easily figure out for yourself. All around it’s a fairly brilliant idea on Moore’s part, one that is initially frustrating as you try to make sense of the jargon on the page but once you realize how you’re supposed to interpret what is being said it makes the story far more interesting. It’s all a rather cool idea, but one that stumbles at times because of how it is presented. If you’ve got the patience to decode everything that is happening, it’s great. But if you’re someone who is trying to decipher the plot quickly, it’ll be lost on you and make you think you’re reading a story from a three-year old child.

The most interesting degree to Moore’s vision is how he changes language, taking words that are common to us and giving them a whole new meaning. For example, instead of a character saying something like “I thought about that!” they would say something like “I skulled it!”, with the idea being that using one’s head is part of the action used when it comes to thinking so somewhere along the line the word “think” is completely abandoned in place of the term “skull”. Other examples like the use of the words “and but” in conjunction with each other show that sentence structure was damaged somewhere in the midst of the past one hundred years as the use of the word “and” in that instance is unnecessary as “and but” together in Moore’s world translates plainly to “but”. The way words are used here is fascinating because it’s meant to be oversimplified to imply to the reader that language has taken a step back towards something like that of the Neanderthals but then the overuse of some words shows that logic is still there, it’s just misplaced. Another interesting decision Moore makes with his language structure is the emphasis on curse words, having some of them become more common than the word “the”. Moore uses the “f-word” in such a casual way that it actually has multiple meanings on top of its standard meaning that we’ve become used to. Other words like “brown/browned” have foul meanings as well, that you can easily figure out for yourself. All around it’s a fairly brilliant idea on Moore’s part, one that is initially frustrating as you try to make sense of the jargon on the page but once you realize how you’re supposed to interpret what is being said it makes the story far more interesting. It’s all a rather cool idea, but one that stumbles at times because of how it is presented. If you’ve got the patience to decode everything that is happening, it’s great. But if you’re someone who is trying to decipher the plot quickly, it’ll be lost on you and make you think you’re reading a story from a three-year old child.

Truth be told, the characters are probably the least interesting part of this story, so much so that I feel bored just writing a paragraph about them. Within the first three issues, half the characters that you feel like you should care about are killed for the sake of having something happen. Let’s just make characters and plot one paragraph instead so that way it’s a more engaging paragraph to read. The plot itself, much like the characters, is awful through the first three to four issues. You keep hoping for something, anything to happen but the arduous task of decoding Moore’s “new” language as well as understanding the rules of the world he’s building attempt to distract you from the slow-moving plot. As I said, virtually nothing happens plot wise throughout the first three issues, or at least it feels that way. Death for the sake of death is all that really seems to strike a chord in this one, although a death that seems like a throw away turns out to be a significant piece of the puzzle Moore is creating, you just have to be patient for the payoff. That’s essentially what Crossed +100 all boils down to, patience. If you’re willing to try to grasp the language Moore is creating, the world he’s building, and the plot he’s crafting, your patience will be paid off by a dramatic final two issues. When you see the pieces of the plot Moore began developing from issue one begin to payoff in issue six, all that jargon you climbed through feels worth it. With this being a Crossed story, one would expect tons of nudity and gratuitous violence but even that feels like it’s toned down ever so slightly for the sake of Moore’s vision, instead favouring the slow burn plot that kicks it up a notch in the final twenty to thirty pages.

Collects: Crossed +100 #1-6

Best Character: Future Taylor

Best Line Of Dialogue/Caption: “I refuse to pick a meaningful piece of dialogue from this graphic novel because I had to work extra hard to decode the true meaning behind the language and if I put down some of this crazy talk in quotations for this post, you all might think I’m an idiot.” – Dylan Routledge

Best Scene/Moment: Everything adds up – Issue 6

Best Issue: Issue 6. It isn’t even a contest. After fighting your way through four and a half slow issues, the halfway mark of issue five becomes the first, highly interesting moment of the series with that momentum carried forward into the final issue in issue six. The simmering plot boils over in this issue with everything paying off with a conclusion that should feel shockingly obvious but also rightfully deserved. You feel as though you earn this ending, regardless of whether you deem it a good or bad one. It’s not like this entire series is mind-blowing but it’s enough to show you that Alan Moore does still have some tricks up his sleeve that can surprise a reader.

Why You Should Read It: You should read this story to see how world building should be done, even if it isn’t necessarily done well the entire time. When it comes to world building in comics, it feels like a lot of writers today always seem to forget how important language is when showing a distant past or a far away future setting. People change and evolve or in some instances, devolve, something that Alan Moore shows clearly with this story. It’s not perfect but it’s not all awful either, showing the reader that patience and persistence can often lead to a compelling read even if it doesn’t seem that way from the start.

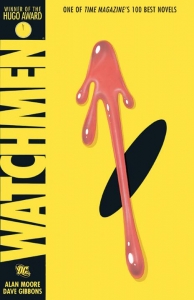

Watchmen

Alan Moore’s most famous work is easily The Watchmen, a story set in the late ’80’s that follows the lives of superheroes after they’ve been forced out of doing their jobs as heroes. That one sentence is about the most underwhelming way to describe the series but I hope the paragraphs that follow below help to balance that out a bit. Widely regarded as the greatest comic book ever written (and rightfully so), The Watchmen did wonders for Moore’s career, making him a media celebrity as well as resulting in him swearing off conventions following some unfortunate incidences with fans. The Watchmen is a comic that changed the landscape of the medium, with the story being so brilliant that the scripts were actually being passed around the offices at DC as they were being completed so that eager employees could read the enthralling story.

Alan Moore’s most famous work is easily The Watchmen, a story set in the late ’80’s that follows the lives of superheroes after they’ve been forced out of doing their jobs as heroes. That one sentence is about the most underwhelming way to describe the series but I hope the paragraphs that follow below help to balance that out a bit. Widely regarded as the greatest comic book ever written (and rightfully so), The Watchmen did wonders for Moore’s career, making him a media celebrity as well as resulting in him swearing off conventions following some unfortunate incidences with fans. The Watchmen is a comic that changed the landscape of the medium, with the story being so brilliant that the scripts were actually being passed around the offices at DC as they were being completed so that eager employees could read the enthralling story.

On a chilly October evening, a heinous act is committed as a man is tossed from the window of his apartment, becoming a whole new kind of street art. With signs of a struggle, it’s clear that this wasn’t an accident; it was murder. This murder sends a shock wave to everyone who knew who the victim was. To some he was an ordinary man, but to a small, select community he was The Comedian, a “superhero” from decades gone by who was part of the crime fighting team referred to as The Watchmen. Rorschach, one of The Comedian’s former teammates, begins investigating the murder, hoping to uncover any sort of clues that may reveal what exactly transpired and resulted in The Comedian’s death. With evidence quickly mounting, Rorschach is convinced that someone is targeting former superheroes in an attempt to pick them off one by one. With all of the former members of The Watchmen having taken on separate, secret lives since they were forced by the government to disband decades ago, an eerie feeling begins to creep over everyone that nothing is sacred or safe. As the mystery begins to unravel, it is revealed that incidences that appear to be targeting the former Watchmen may all be part of a larger plot that threatens the world as we know it.

What else is there to say other than Alan Moore crafts a masterpiece, with what is easily the greatest comic of all time with The Watchmen. Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons work together to bring to life a comic that worked to redefine what “serious storytelling” was within the comic book medium, using Watchmen as a defining point in both of their careers. On the surface, Watchmen is a superhero crime/mystery story but when you sink in underneath all the layers of what’s actually going on in the story, you come to realize the multiple themes that are all consistently at play throughout the story. As a whole, Watchmen is a larger examination of the superhero genre, exposing its tropes as well as going to incredible lengths to point out how these tropes or struggles these heroes face could all be dealt with. Set against the backdrop of an impending third World War, what good are superheroes who can’t even prevent such a terrible event? That is just one of numerous questions that Moore and Gibbons tackle and eviscerate with what is simply the best comic book story ever.

Truth be told, Watchmen is such a rich source of fiction that I could easily write a ten-thousand word article on it, but I’ve got to keep these posts trimmed and lean so to dissect everything great about the story would take more time than I can currently afford. To start from the top with the characters, Moore and Gibbons take your archetype superhero characters and makes key changes to how they should act to make these characters important pieces of a larger machine. The first and most important difference that separates each and every main character from each other is their “world view”, as highlighted by the back matter in the collected edition I used for reviewing the story. Doctor Manhattan is the equivalent of a near-omnipotent being, viewing the world as a subatomic structure. He can’t comprehend the importance of human life because, in sharp comparison to the way he sees the world, human life is insignificant. The only reason he attached any value to human life is due to his relationship with Laurie Juspeczyk (a.k.a. The Silk Spectre), with his romantic involvement with her starting as a sexual interest in a younger woman before evolving from there. Even then, it’s more so implied he only keeps the relationship going for a sense of familiarity, with his emotions being wildly out of touch in comparison to that of humans. That’s not to say that Doctor Manhattan is incapable of displaying true emotions, as parts of his previous human life do come blasting through at times, it’s just that due to the way he sees the world, everything is so much smaller in comparison to the tiny miracles that he can see but the world can’t even comprehend.

The character of Dan Dreigberg/Nite-Owl is apparently supposed to be modelled after the DC character of Ted Kord/Blue Beetle. He’s wealthy, highly intelligent, and parallels the character in a lot of ways, deciding to fight crime because he has the expendable income to do it. Alan Moore attempts to capture the idea of escapism through the superhero genre by using Dan Dreigberg, displaying the alternating sides to Dan and Nite-Owl as polar opposites, as Nite-Owl is Dan’s escape from his day-to-day life. It’s heavily implied that Dan is impotent outside of the costume, being a nervous, uncomfortable man who can’t perform sexually because, in stark contrast to his alter-ego of Nite-Owl, he is weak. It’s suggested that Dan as Nite-Owl had a sexual relationship with one of his villains, which furthers the point of Nite-Owl being the stronger side of Dan, who is unsure of how he views the world. As Nite-Owl, Dan feels confident in how he draws in women because that’s the side that attracted the villain of whom he assumed a relationship with. The woman wanted Nite-Owl, as revealed by a signed picture addressed in such a way, but she had no interest in Dan Dreigberg. This concept is furthered when Laurie Juspeczyk pursues Dan and he is unable to have sex with her. Later in that same issue, and in full costume, Dan is overcome with a sense of confidence, now able to sleep with Laurie while she is also in her costume. The rush of adrenaline to saving a life, the secrecy, the bravery, the heroism; it’s all there in this issue and is a brilliantly simple character study of what makes Dan Dreigberg tick. To a further point, Watchmen itself is a giant character study with nearly every issue taking an immediate character focus but hiding it beneath a plot of mystery that tries to keep you focused on where things are going instead of what is immediately occurring.

The character of Dan Dreigberg/Nite-Owl is apparently supposed to be modelled after the DC character of Ted Kord/Blue Beetle. He’s wealthy, highly intelligent, and parallels the character in a lot of ways, deciding to fight crime because he has the expendable income to do it. Alan Moore attempts to capture the idea of escapism through the superhero genre by using Dan Dreigberg, displaying the alternating sides to Dan and Nite-Owl as polar opposites, as Nite-Owl is Dan’s escape from his day-to-day life. It’s heavily implied that Dan is impotent outside of the costume, being a nervous, uncomfortable man who can’t perform sexually because, in stark contrast to his alter-ego of Nite-Owl, he is weak. It’s suggested that Dan as Nite-Owl had a sexual relationship with one of his villains, which furthers the point of Nite-Owl being the stronger side of Dan, who is unsure of how he views the world. As Nite-Owl, Dan feels confident in how he draws in women because that’s the side that attracted the villain of whom he assumed a relationship with. The woman wanted Nite-Owl, as revealed by a signed picture addressed in such a way, but she had no interest in Dan Dreigberg. This concept is furthered when Laurie Juspeczyk pursues Dan and he is unable to have sex with her. Later in that same issue, and in full costume, Dan is overcome with a sense of confidence, now able to sleep with Laurie while she is also in her costume. The rush of adrenaline to saving a life, the secrecy, the bravery, the heroism; it’s all there in this issue and is a brilliantly simple character study of what makes Dan Dreigberg tick. To a further point, Watchmen itself is a giant character study with nearly every issue taking an immediate character focus but hiding it beneath a plot of mystery that tries to keep you focused on where things are going instead of what is immediately occurring.

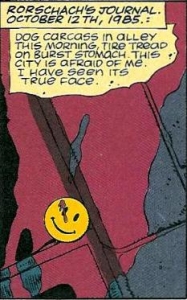

When it comes to your other primary characters of Rorshach, Silk Spectre, and Ozymandias, all three characters have incredibly different views to match that of Nite-Owl and Doctor Manhattan as well. Rorshach is your brooding presence of the story, seeing the darkness in the world that needs to be exterminated. To him, heroes are an essential part of what keeps the criminal element in check, believing that a hero should do whatever it takes to keep evil at bay. Silk Spectre is a far more delicate character, a disappointing truth for the only true female lead to the story but one that still rings true due to her general level of innocence. Laurie is reflective of your average human being, as she possesses no powers and, as a hero, brings nothing unique to the table. She’s a more than capable fighter and someone who wants to do good but isn’t necessarily capable of balancing out what comes after taking preventative actions. Ozymandias is a man with a larger world view than the rest of your human characters in your story, seeing himself at the centre of everything. He learns quickly how foolish it is to believe that evil is exclusive to a criminal element, something that Rorshach is incapable of grasping due to his psychological state. Ozymandias is referred to as the “World’s Smartest Man” and with that comes the burden of trying to find a solution for the world’s problems. What makes Ozymandias such a fascinating character is his capability to not blur the line between right and wrong, fully understanding the merits and necessity to use both sides of the spectrum to try to inevitable achieve peace.

Cutting to the chase, when it comes to the plot, Moore and Gibbons do plenty of brilliant work with each issue to further the many moving pieces towards the grand finale you encounter in the final two issues of the story. There are constant gears churning from the opening salvos of this story, building multiple layers of fiction for the reader to become engrossed in. From the rich back matter at the end of every issue, to the comic book story “Tales Of The Black Freighter” that occurs within the comic itself, to every bit of symbolism that is packed into this story, rest assured that you’ll take something new every time you crack this book open. In regards to the “Tales Of The Black Freighter” story that unfolds, a comic read by a young man named Burnie in New York while the rest of the story unfolds, there is so much more importance based on that tale than what most people realize when they read this comic. The Black Freighter story feeds off of Ozymandias’ story brilliantly, especially as both of those stories peak in the greater issues. Without spoiling it for people who have still yet to read this comic for some crazy reason, the themes that Moore plays at repeatedly for the duration of the comic all cleanly feed into the Black Freighter tale, which in and of itself is wildly important because it helps to highlight how different this world has become with superheroes actually being a prevalent part of our society. The youth culture would have no interest in superhero stories with these heroes cropping up around the Vietnam era in American history, pushing them to take in other forms of fiction like stories about pirates and horror. The world building that Moore and Gibbons do is so deep that it’s just lost on the reader at times, requiring multiple readings to pick up on more of what they are trying to suggest.

Collects: Watchmen #1-12.

Best Character: Ozymandias.

Best Line Of Dialogue/Caption: “The accumulated filth of all their sex and murder will foam up about their waists and all the whores and the politicians will look up and shout “Save us!”… and I’ll look down, and whisper “no.” – Rorshach.

Best Scene/Moment: The realization sets in – Issue 12.

Best Issue: Issue 6. This is the defining issue for the character of Nite-Owl/Dan Dreigberg as it exposes his feeling of impotence and helps to define the escapism of the superhero genre. We see the struggles Dan faces in feeling confident in himself outside of his costume as well as how empowering being in the costume is for him. There’s a scene with no text where Dan has a nightmare that perfectly captures everything you need to know about the character. What’s even better about this issue is Moore and Gibbons begin to hint at all the key pieces for the stories finale in the background on a television screen through the commercials that play out on it. It just goes to show the reader that everything done in the story is highly deliberate and completely necessary for the vision that Moore and Gibbons had. Pay attention for pages twelve to twenty-one because they spell it all out for you.

Why You Should Read It: Watchmen was Alan Moore’s response to the statement “Comics aren’t a medium for serious storytelling”. With Watchmen, Alan Moore not only completely discredits that stance but he does so with a story about superheroes just to twist the knife a little bit further. The layers of metafiction, the way the characters are built, the layer upon layer of subtle themes that you can miss through just a surface reading, it’s all there and it’s a bloody masterpiece. There’s a reason I chose Watchmen for the final post of this weekly challenge and that’s because I truly saved the best for last. There isn’t a comic that excels at using this medium to tell a story anywhere nearly as well as Watchmen does. That’s not a bold statement on my behalf, it’s a simple fact. The story shows you that being a hero doesn’t mean you’re always the good guy, just read issue twelve and you’ll see what I mean.

I’ve loved this series – can’t believe it’s been a year already! I thought it’d lose steam along the way but there really is 52 (at least) brilliant writers worth highlighting. Lucky us 🙂 Thanks for the hard work guys!

Dylan I want to congratulate you on a job well done – you certainly “met the challenge”.

This overview of different writers certainly brought back some good memories and introduced me to some new talent that I have heard about, but knew very little of prior to your posts.

It was a mammoth undertaking and much appreciated by fans of all stripes here on the site.

Thanks Dylan, I really enjoyed this series. It introduced me to some great reads.