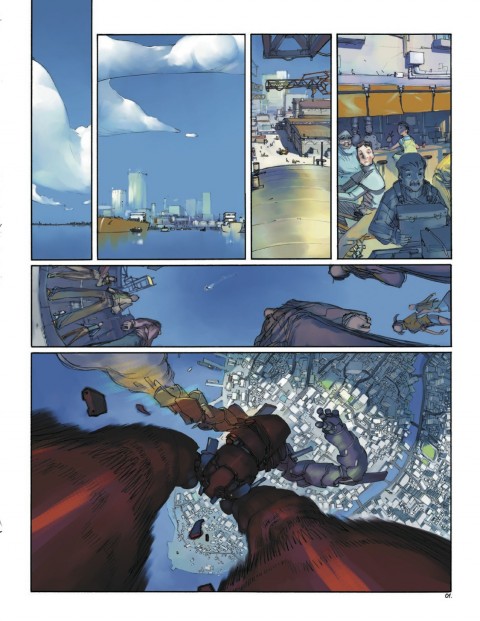

MEKA

Meka starts big, introducing a world in which enormous human-piloted machines face off against equally enormous enemy machines. These are in the classic Giant Robot vein, but Bengal makes them seem fresh anyway, and his efforts to emphasize the ridiculous scale of these machines put a huge smile on my face by the third page. (I will say that his main protagonist Meka seems to have a hell of a field of view problem.)

But the big, flashy beginning gives way to a human-scaled story of the machine’s pilot and engineer, who are stranded when their Meka takes a beating and their rescue beacon fails. They must first figure out how to escape their hulking, broken vessel and then survive against a world that is even less hospitable.

Bengal paints the story of Lieutenant Llamas and Corporal Onoo in fine pencils and bright colors that might seem garish if the subject matter itself wasn’t already larger than life. These pages were originally published in two 40-ish-page Euro-format albums, but here are collected in a handsome 96-page hardcover. But even so the story seems over too quickly, and I as a reader was left cheering for more. This relatively slim volume contained some of the best action sequences I’ve seen in comics, which is impressive considering this was Bengal’s first published work. If this series finds an English-language audience, who knows, maybe we’ll get more adventures with Llamas and Onoo.

Bengal’s art is an almost perfect amalgamation of his Asian and European influences. His figurework and movement are reminiscent of top-shelf manga and his colors and paneling are heavily influenced by the euro greats. His characters pop off the page, and his movement and balance keep the eyes skating across the panels, but not too quickly.

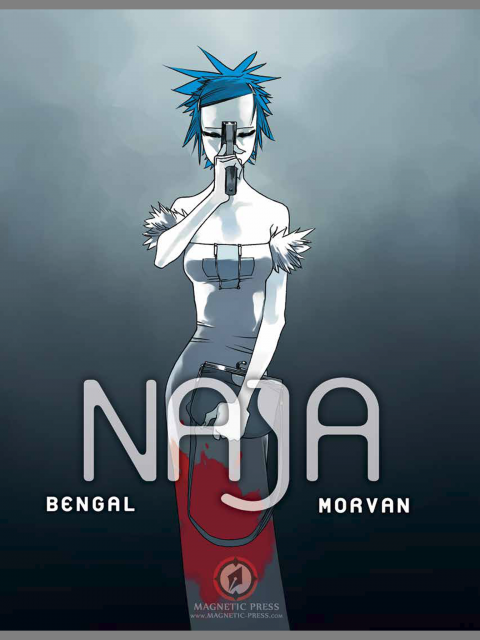

NAJA

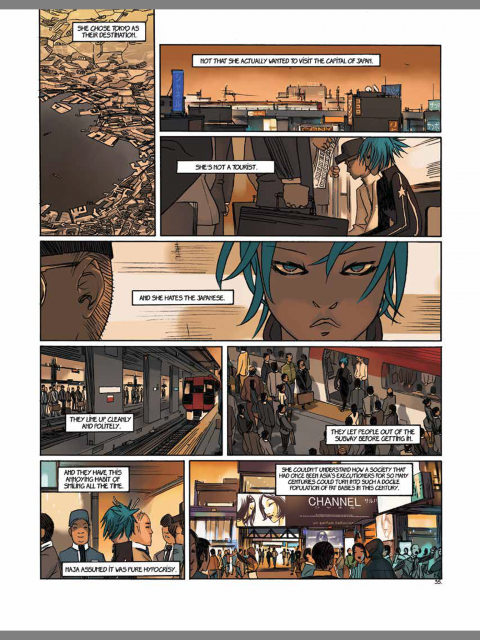

Naja once again features the amazing art of Bengal, but is a different kind of story all together.

Turning trauma into a superpower is an interesting trope. A character often experiences awful abuse or a horrific accident or attack, and their response is to become a hyper-aware revenge machine. Sometimes they have a “code,” like Batman or Dexter. Other times they become seemingly-remorsless killers. I can tell you that this is a very unlikely outcome of childhood trauma, but it nonetheless seems to be a common way to create a morally-compromised hero. In Naja’s case, she is left emotionally blank and without the ability to feel physical pain. (In most true-life cases, the reverse is true.) It’s easy to see how the hyper-vigilance often displayed by trauma victims could be useful in life as a super spy/assassin, but the physical exhausting that accompanies that “ability” is often left out.

But Naja and her fellow assassins are not typical survivors of trauma. Indeed, they are extraordinarily skilled, and are the top three assassins in the world. In Naja’s case, she kills because it is a job that pays well, and because she has somehow become particularly skilled at it. Her fellow assassins represent two alternative motives for killing: Killing only for “good” causes, whether real or simply believed; and simple psychopathy.

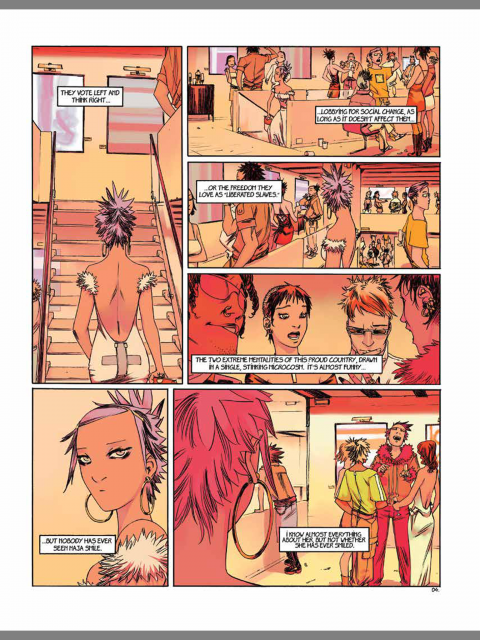

Naja’s tale is told by a rather interesting and wholly unreliable narrator, and his motivations both deepen and become more opaque as the story progresses. Meanwhile, Naja becomes both more unlikeable (her misanthropy knows no limits) and more sympathetic as the tragedy of her backstory is revealed.

Naja and Meka will both be available at San Diego Comic Con in July at booth #1620. Both are available for preorder at magneticpress.bigcartel.com. Naja is expected to be released in late July and Meka in mid-August. Digital copies were provided by Magnetic Press for the purposes of these reviews

A big thanks to Magnetic Press for introducing Bengal and JD Morvan to English-speaking audiences, and doing it right by publishing hardback collections of these exciting works.

More pages from Meka and Naja:

the way the narrator unfold Naja’s story is a little bit in off the beaten path, regardless how he narrates it I still like how the story is put together