One of the most common requests I receive from readers of Forgotten Silver is to write about minicomics from the 1980s more often. Last year, I wrote columns about the early works of Chester Brown and also covered the work of FreeKluck in June and July last year. It has been some time since my series of articles about FreeKluck and I thought now would be a good time to return to the minicomics again. This month’s edition of Forgotten Silver looks at the early work of one of the best-known Canadian underground creators from the era: Julie Doucet.

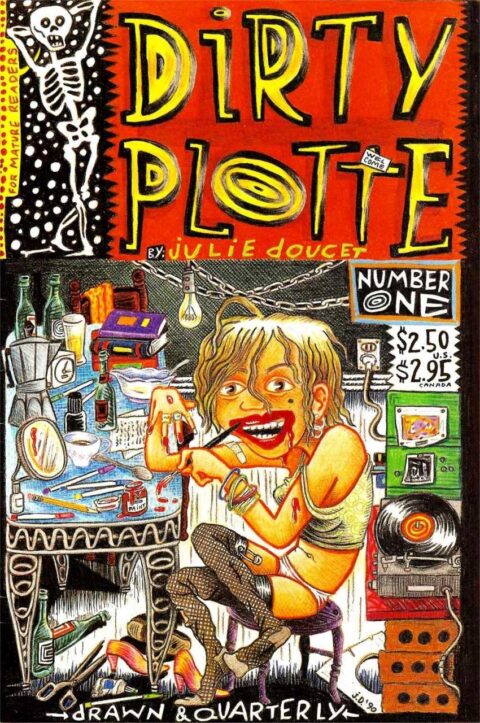

Julie Doucet is a unique talent for several reasons. One of the few women working in minicomics in Canada during the 1980s, she was also one of the few minicomics creators to transition to her own comic book series in the 1990s with Drawn & Quarterly (among other notables such as Chester Brown and American ex-patriot Joe Matt). Like Chester Brown, Seth and Joe Matt, she was at the forefront of the autobiographical comics movement in Canada. To call her work “autobiographical” is something of a misnomer, as her comics feature a fictionalized version of herself depicted in transgressive fantasies. As the result, her series Dirty Plotte for Drawn & Quarterly was critically acclaimed and led to Doucet becoming one of the rising stars of the independent scene in the early 1990s. Arguably, she was Canada’s first major independent comic book star of the new decade.

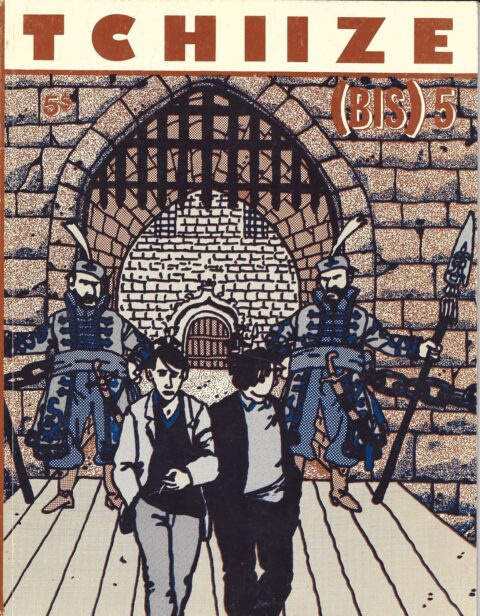

Doucet was born in Montreal in December 1965. She grew up in the city, where she attended a Catholic high school and then Cégep before starting university in 1985 at l’Université du Québec á Montréal. As a teenager, Doucet was already honing her skills as an artist and soon after starting university, she caught the eye of fellow bandes dessinées creators associated with Tchiize! bis. The seven-issue series was produced by Yves Millet irregularly from 1985-1988 and exposed Doucet to the broader Montreal underground scene at the time (such as Henriette Valium and Martin Lemm).

Much of Doucet’s earliest work in comics tended to be small contributions to the anthology comics that were being produced around Montreal at the time. This changed when she learned about Factsheet Five, an international directory of zine reviews, which expanded her knowledge about the zine subculture across North America. The realization that she could create her own comics with a Xerox machine led to her creating her own zine.

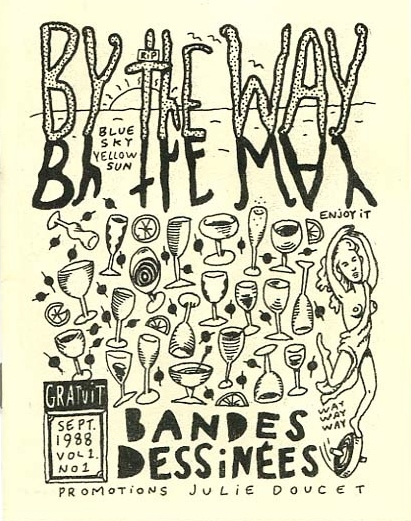

By 1988, Doucet had dropped out of university, gone on welfare, and was working part-time at a copy shop (which gave her access to a photocopier). Her first attempt at creating her own zine was the 1988 one-shot By the Way. She distributed these for free and it is not clear how many copies she produced, but I have to assume that this comic was extremely limited.

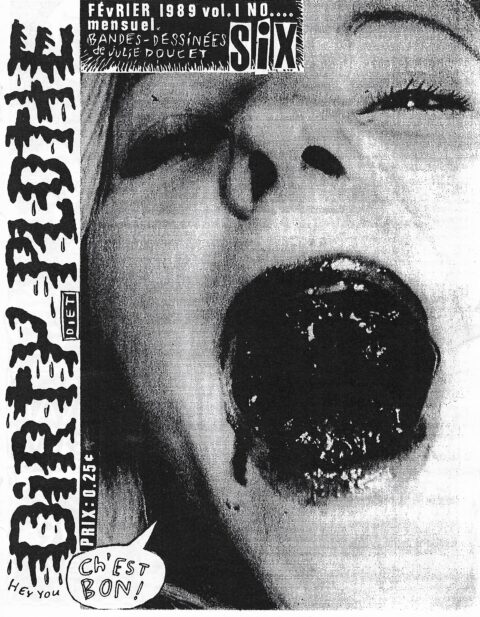

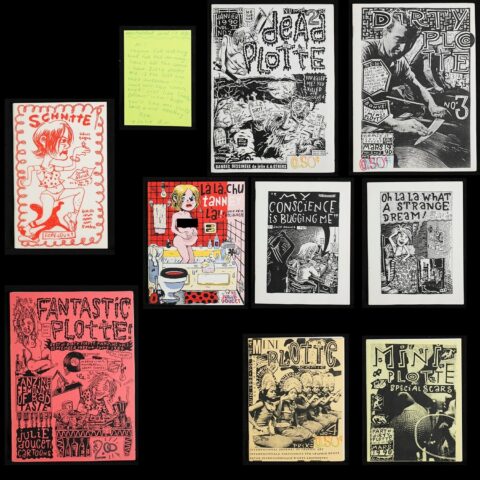

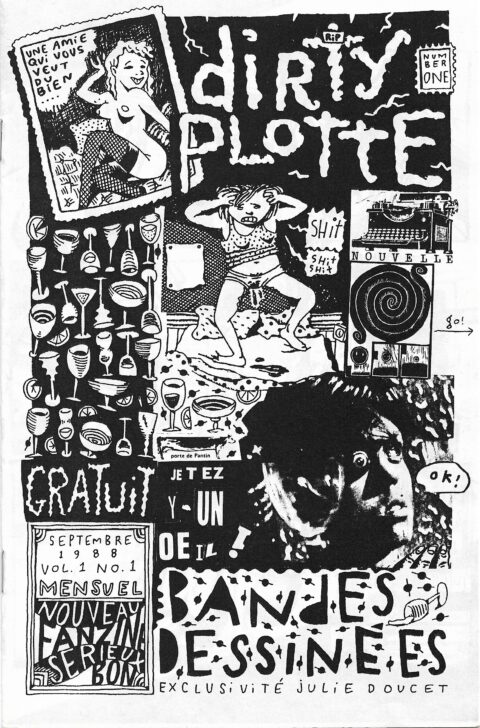

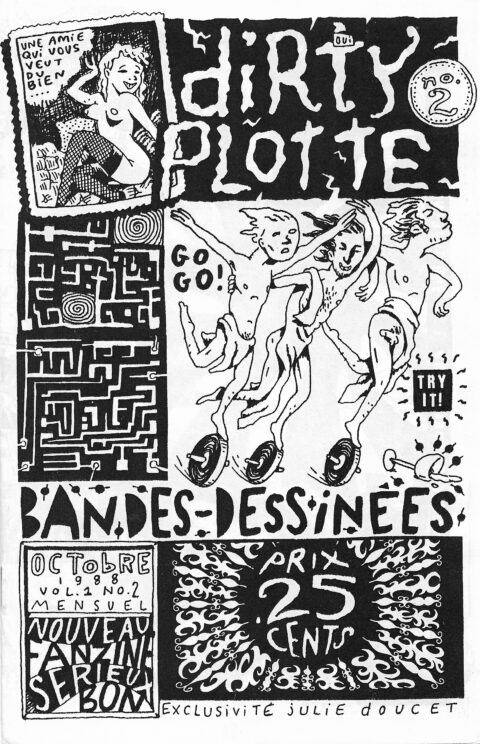

Within a month, Doucet had released the first issue of her minicomic Dirty Plotte, with the first issue debuting in September 1988. Like By the Way, the first issue of Dirty Plotte was distributed for free. Subsequent issues of the series would cost $0.25 each. The first two issues of the series were twelve pages long, while later issues were eight pages long. Doucet initially stuck to her monthly schedule, releasing at least one new issue every month from September 1988 to June 1989.

Like many minicomic series that began in the late-1980s, Dirty Plotte was a small fish in a big pond. When minicomics were uncommon at the beginning of the decade, they seemed cutting edge. Creators on both sides of the border (such as FreeKluck, Chester Brown and Colin Upton in Canada and especially Clay Geerdes and Brad W. Foster in the USA) who were ahead of the curve were able to attract notoriety and, in some cases, critical acclaim. Most of these minicomics were created by men and relied on transgressive humour, sex and/or satire to appeal to their audiences. Many of the comics churned out at this time were juvenile, but there were many gems too. When one starts to think about the sheer volume of minicomics (and fanzines of all kinds) that proliferated at this time, it is incredible that anyone ever took notice of Julie Doucet.

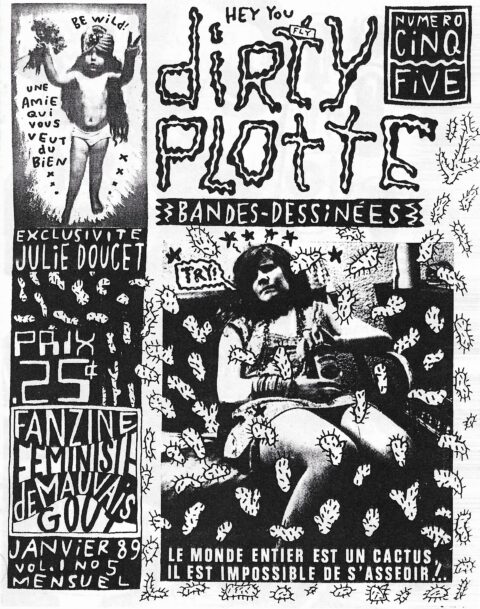

On this note, it is worth considering that issues of Dirty Plotte had small print runs of between 150 and 200 copies each. My research suggests that the print runs increased as the series went on, but only incrementally. The series is gross. It is transgressive in ways that are part and parcel of some genres of minicomics, but unlike many of the minis from the era, Dirty Plotte is not presented from the male gaze. It is a feminist publication in an era where such publications were few and far between and also during an era when the audience was predominantly male. Perhaps the most difficult thing about Doucet’s work for an audience outside of Quebec is that the comic requires the reader to have a working understanding of both French and English: each issue has stories in both languages.

Even the title of the series itself works as a double entendre that requires a working knowledge of French and English to fully appreciate. The word “plotte” is vulgar Quebecois slang for a woman’s vagina. In English, when we hear the word, it sounds like “plot,” which English speakers know refers to the course of an unfolding story. So, Dirty Plotte can be interpreted simultaneously as meaning “dirty vagina” and “dirty plot.” It is brilliant in its simplicity but easily lost on people who are not bilingual.

On the surface, the potential target audience for this series seems extremely limited given the language barriers for potential readers. Combining this with the plethora of minicomics that were being released at the time and the contraction of the independent comic scene during the late-1980s, how did Julie Doucet ever get noticed outside of Quebec? The short answer is that she started sending review copies of Dirty Plotte to Factsheet Five. Her comics were well-received and somebody famous took notice.

The sixth issue of Dirty Plotte contained a four-page French-language story called “E: Ni Manique!” The story features Julie in the middle of a rough period realizing that she has run out of tampons. This leads to her becoming enraged, growing into a gargantuan, grotesque version of herself and going on a rampage through the city. The rampage ends after emergency responders present her with tampons, which calm her down and bring her back to normal size. This four-page story caught the attention of Aline Kominsky-Crumb, who was one of the originators of feminist underground comics (participating in early issues of the famed 1970s underground anthology Wimmin’s Comix). Kominsky-Crumb was herself a pioneer when it came to using female bodily functions to break ground in the comics industry.

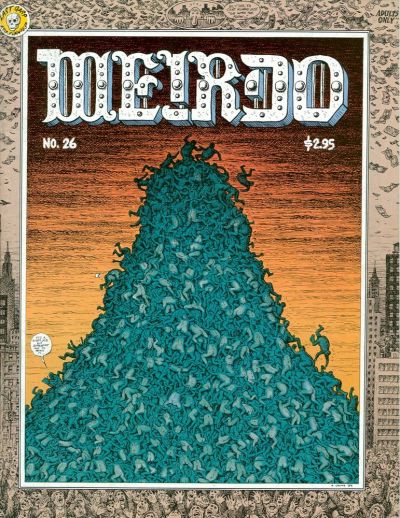

At the time, Kominsky-Crumb was the editor of Weirdo, the magazine-sized anthology comic created by her famous husband, Robert Crumb. She was also starting to put together the roster for what would become one of the seminal texts of feminist comics from the early-1990s, Twisted Sisters: A Collection of Bad Girl Art (which was released by Penguin in 1991 to critical acclaim and led to a four-issue series with Kitchen Sink). Kominsky-Crumb would solicit “E: Ni Manique” for the Fall 1989 issue of Weirdo, with the strip translated to English and retitled “Heavy Flow.”

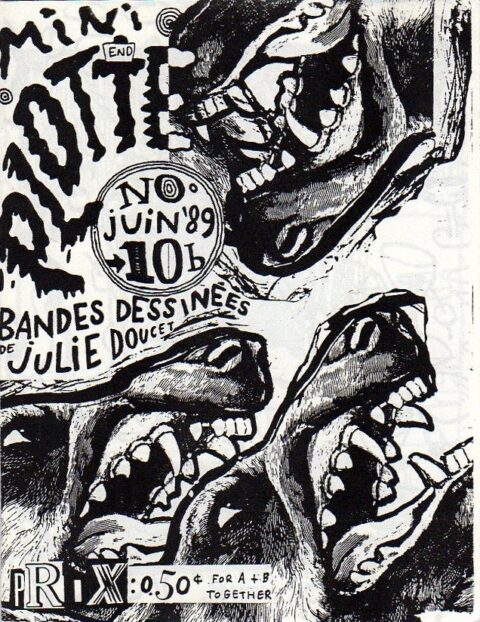

Prior to her big break with Kominsky-Crumb, Doucet continued to self-publish monthly issues of Dirty Plotte. Issue # 7, however, brought a change in style for the series and can lead to confusion for collectors because of its numbering: Issue # 7 was released in two parts (# 7a and #7b) in March 1989. Doucet would repeat this numbering with issues # 10a and 10b in June 1989. Issues # 8 and 9 of the series would follow regular numbering but would increase in size and now cost $0.50. Issue # 10b would be the final issue of the series’ first volume. Both issues of # 7 and # 10 would be referred to as “Mini Plotte,” further confusing the titling and numbering for collectors.

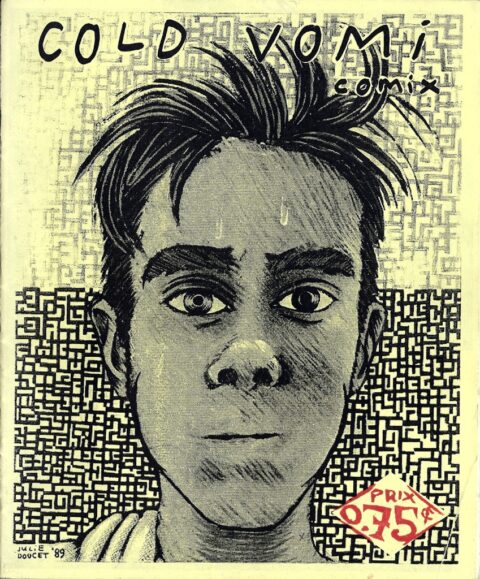

After the first volume of Dirty Plotte came to an end in June 1989, Doucet teamed up with fellow Martin Lemm to create the one-shot minicomic Cold Vomi. Lemm would subsequently release his own well-regarded minicomic series Zen Zen Shit beginning in 1990.

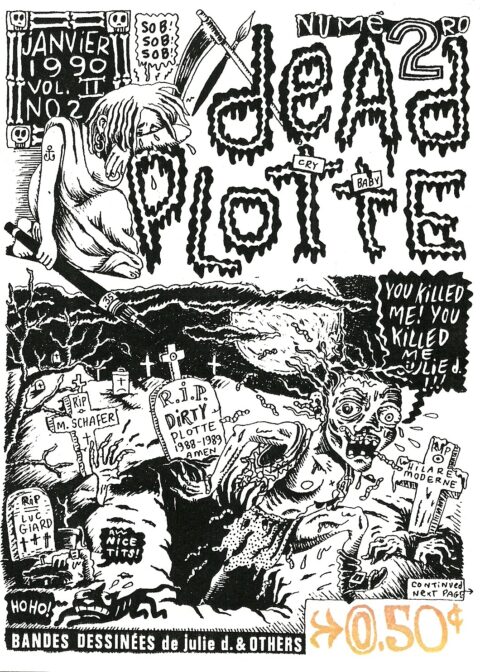

Dirty Plotte would return in September 1989, with its second volume. The second volume would last for four issues and would feature contributions from other artists, such as John Porcellino (whose earlier series King-Cat was a favourite of Doucet’s). The first issue returned to the $0.25 cover price, but subsequent issues would be $0.50. The second issue of Vol. 2 was titled “Dead Plotte.” The third issue was called “Dirty Plotte,” but included a bonus mini called “Mini Plotte: Special Scars.” The final issue of Vol. 2, released in June 1990, was called “Mini Plotte.” Doucet would only release one additional minicomic as part of Dirty Plotte, a greatest hits compilation of sorts called Fantastic Plotte. Some sources say that the comic was never released, but a copy surfaced on eBay as part of a collection of original Julie Doucet minis in May 2020.

According to most accounts, the original Dirty Plotte minicomics came to an end because Doucet came to an agreement to publish the series with Montreal’s Drawn & Quarterly, beginning in January 1991. Doucet would publish twelve issues of the series irregularly from 1991 to 1998 when the series came to an end. Most (if not all) of Doucet’s work from her minicomics were reprinted or recreated for the Drawn & Quarterly series. Despite only releasing four issues of Dirty Plotte for Drawn & Quarterly in 1991 (which would be her most prolific year), she was nominated for the Harvey Award for Best New Series and won the Harvey Award for Best New Talent (she lost the Best New Series Award to Peter Bagge’s series Hate).

Soon after she started publishing with Drawn & Quarterly, Doucet moved to New York City. She moved again after a year in New York to Seattle, before settling in Berlin in 1995. She returned to Montreal in 1998, as Dirty Plotte was coming to an end. Doucet continued in comics off and on after ending Dirty Plotte, releasing several critically acclaimed graphic novels. Yet, she ultimately has distanced herself from comics for much of the past two decades to focus on other artistic endeavours. She does release comic material from time to time and continues to be a fixture of the broader Montreal arts scene. Doucet was inducted into the Joe Shuster Awards’ Canadian Comic Book Hall of Fame in 2017.

Doucet remains one of the most important female comic creators to have ever come out of Canada. She emerged on the scene in Quebec as the Canadian Silver Age was coming to an end and was one of only a handful of Canadian minicomics creators to transition to their own regular comic series at the dawn of the Modern Age. This was no small feat in an era when the industry was contracting. Doucet was also a key creator in the emergence of Drawn & Quarterly and contributed to the company’s early success. Drawn & Quarterly is the longest-running Canadian comic company of all time (after Aardvark-Vanaheim, with the caveat that A-V only publishes Dave Sim’s work). It is hard to imagine how the Canadian comic book industry would have unfolded over the past three decades without Drawn & Quarterly leading the way.

Collectors hoping to acquire issues of Doucet’s original minicomics should anticipate this being a herculean task. Unlike some other well-known Canadian minicomic creators from the 1980s (such as Chester Brown and Colin Upton), Doucet did not release second printings of her minis. With print runs of 200 copies or less, issues of both volumes of Dirty Plotte, her original minicomic By the Way and her comic with Martin Lemm, Cold Vomi, rarely come up for sale. When they do, they tend to fetch high sums. It has been a couple of years since the last copies of any of these minicomics have come to market for sale individually. The last time that a noteworthy collection appeared was in December 2018. The said collection included several issues from Vol. 1 and Cold Vomi, which were all sold separately. Cold Vomi flew under the radar, selling for only $15 CAD at the time. On the other hand, Vol. 1 # 1 sold for over $200 CAD, while issues # 2 and 3 from Vol. 1 sold for around $100 CAD each. Several other issues from the first volume sold for around $50 CAD each at the time. Given that these sale prices are now several years old, they should be considered out of date.

Including both volumes of Dirty Plotte, By the Way, and Cold Vomi, Doucet’s self-published minicomics total only eighteen issues. If Fantastic Plotte was properly released, this number increases to nineteen minicomics. All things being equal if you have an opportunity to purchase any of Doucet’s original minis you should do so. Individual issues are virtually impossible to find. Nevertheless, there are three key issues that I would recommend focusing on if you have an opportunity to purchase any of these minis. The first two are the most obvious: By the Way, which was Doucet’s first self-published minicomic and Dirty Plotte Vol. 1 # 1 are the two comics that started it all. However, the most important key issue among these comics is Dirty Plotte Vol. 1 # 6, which features “Heavy Flow,” the story that made Doucet famous.

Since collecting the entire series of original Doucet minis will not be possible for most collectors, the good news is that the Drawn & Quarterly series is quite affordable on the secondary market and (from what I understand) the series reprints most, if not all, of Doucet’s strips from her original minis. Drawn & Quarterly also has an impressive box set available for sale. If you want to read or collect Doucet, but are not willing to break the bank or spend years looking for comics that may never come to market there are other options. Full disclosure: I have been searching for issues of these minicomics for nearly five years and own only six of them. As such, I wish you the best of luck if you are trying to source these comics. That is, as long as you don’t outbid me!

Great post brian, and one I have been looking forward to. I remember when Harry Kremer first began selling Julie Doucet and had her right up front by the cash register. I am quite familiar with French and, especially, French swearing and just about plotzed when I saw the word “plotte” right at kid level by the cash. Harry was rather amused when I translated for him but he did move the book a bit higher up beyond the reach of little eyes and hands.

That’s quite funny, mel! I imagine that was a “whoops” moment for Mr. Kremer.