As a child growing up in the 1980s and 1990s, I was innocently unaware of the fact that many of the cartoons that I watched were produced in Canada. Companies like Nelvana, Atkinson Film-Arts, Cinar and later Mainframe Entertainment and Lacewood Productions produced or collaborated with international firms to create many of the popular animated television programs of the era, from The Adventures of Teddy Ruxpin and Inspector Gadget to ReBoot and Beast Wars. In addition to this, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) continuously aired animated shorts created by National Film Board (NFB), such as The Log Driver’s Waltz, Special Delivery and The Cat Came Back. CBC also aired The Raccoons, while Nelvana and Atkinson Film-Arts dabbled in creating more adult-oriented animated films such as Rock and Rule (now a cult classic, but then a box office failure) and Heavy Metal, respectively.

In reality, the late-1960s through the mid-1990s was an era of rapid growth for the Canadian animation industry. The history of this industry during the rest of the 20th century is one of starts, stops and limited output. Prior to the creation of the NFB in 1939, the animation industry in Canada was virtually non-existent. Although there was activity in Canada during the 1910s, due to the work of animation pioneers such as Raoul Barré (who first created the “assembly line” style of animation), not much has survived from this early era. In fact, the oldest surviving piece of animation in Canada is the Jack (J.A.) Norling produced The Man Who Woke Up from 1919. Commissioned by the Federal Budget Board of Winnipeg to promote philanthropy, the film is a Dickensian tale of a character styled after Ebenezer Scrooge. Although the film is live-action, it included Norling’s two-minute animated dream sequence. After 1923, Canadian animation experienced a rapid decline until the NFB’s creation. For a detailed examination of the history of silent film era animation in Canada, I recommend Robyn Ludwig’s paper, “Before McLaren: Canadian Animation of the Silent Film Era (1910-1927)”.

Although the NFB came into existence in 1939, it did not produce animation until 1941 after its first commissioner, John Grierson, convinced Scottish animator Norman McLaren and his partner and lover, Canadian Guy Glover, to relocate from New York to join the organization. McLaren’s work with the NFB propelled the Canadian animation industry for the next two decades, while Glover rose up the ranks to become one of the organization’s senior producers and key administrators. McLaren’s first film for the NFB was the short Mail Early, a public service announcement encouraging Canadians to send their Christmas mail early to ensure it would arrive in time for the holiday. McLaren then spent a considerable amount of time working on War Bond films, such as V for Victory (1941) and Dollar Dance (1943). Around the same time, Grierson came to a deal with Disney to produce four animated shorts as part of the Canadian War Savings Plan, featuring popular Disney characters such as Donald Duck: The Thrifty Pig (1941), 7 Wise Dwarfs (1941), Donald’s Decision (1942) and All Together (1942).

The rapid rise of animation at the NFB led to McLaren being unable to keep up with the pace of work. Grierson had difficulty hiring animators due to labour shortages associated with the war, but the NFB ended up sourcing talent from École des beaux-arts de Montréal and the Ontario College of Art and Design. Newly hired artists included now-legendary pioneers of Canadian animation, including René Jodoin, George Dunning, Grant Munro and Evelyn Lambert (arguably the first female animator in Canada). Several of these people would be nominated for Academy Awards, with McLaren winning the Oscar for “Best Documentary (Short Subject)” for his film Neighbours (1952), a live-action film that is an incredible experiment in stop motion animation (and still looks good almost seventy years later).

Despite the success of the NFB in establishing a strong animation scene in Canada, a private animation industry was virtually non-existent during this period. All of this changed with “The Guest Group’s” creation of Rocket Robin Hood in 1966 in collaboration with New York’s Krantz Films. Spearheaded by Al Guest and his partner Jean Mathieson (another major female animator and head of animation on the series), The Guest Group formed into Trillium Productions in Toronto, with the property being owned by Krantz Films, which is most famous for producing Marvel animated cartoons, such as Spider-Man (which featured the voice of Canadian Paul Soles in the title role) and The Marvel Super-Heroes. The entire series aired on CBC and the first two seasons of Rocket Robin Hood were created in Toronto. Unfortunately, with the first season running well over budget, Krantz Films sent the now legendary Ralph Bakshi to Toronto to deal with the troubled production. Bakshi replaced Shamus Culhane of the Guest Group as the in-animation-studio producer and the tone and style of the series changed. Creative and financial disputes between Bakshi and Trillium staff led to the production being moved to New York for its final two seasons, ultimately ending the Guest Group and Trillium in the process.

Rocket Robin Hood remains a cult classic in Canada that has had a direct influence on both comic book creation and the fledgling animation industry that started to flourish in the 1970s. One of the first non-giveaway comics of the Canadian Silver Age, Operation Missile, was created by former Rocket Robin Hood animator Derek Carter. Perhaps more significantly, however, is that the dismantling of The Guest Group occurred at around the same time that the newly established Sheridan College in Oakville, Ontario, first offered courses in classical animation, as part of the vision of the college’s first president, Jack Porter. The college took advantage of the folding of The Guest Group to purchase the company’s cameras and animation equipment and subsequently hired Guest and Mathieson as creative advisors under the new program. Guest and Mathieson would later create a new studio, Rainbow Animation, and hired numerous Sheridan College graduates as key personnel. The company would go on to produce animated sequences for Hamilton’s The Hilarious House of Frightenstein, as well as the Inuit film Ukaliq.

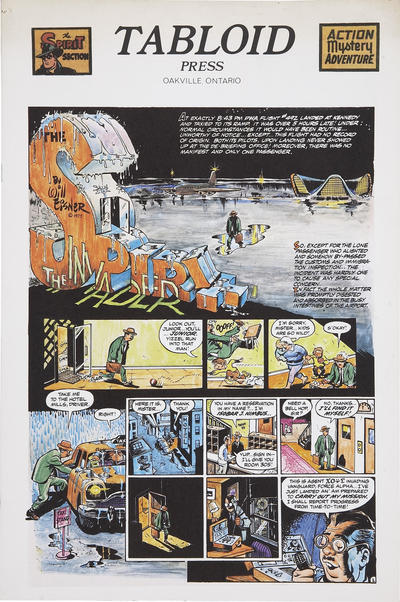

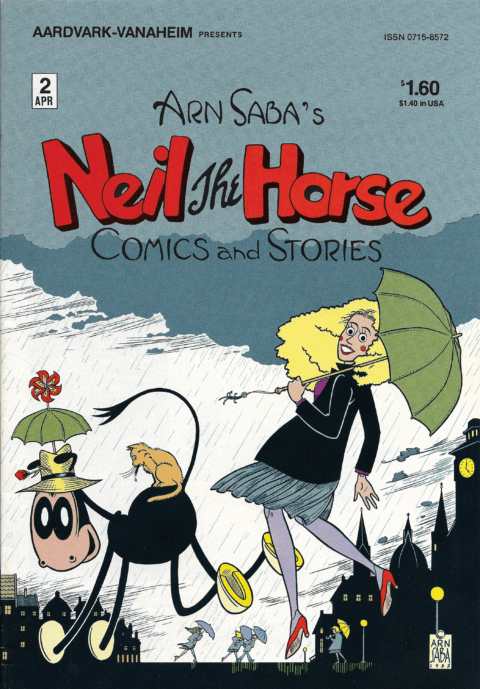

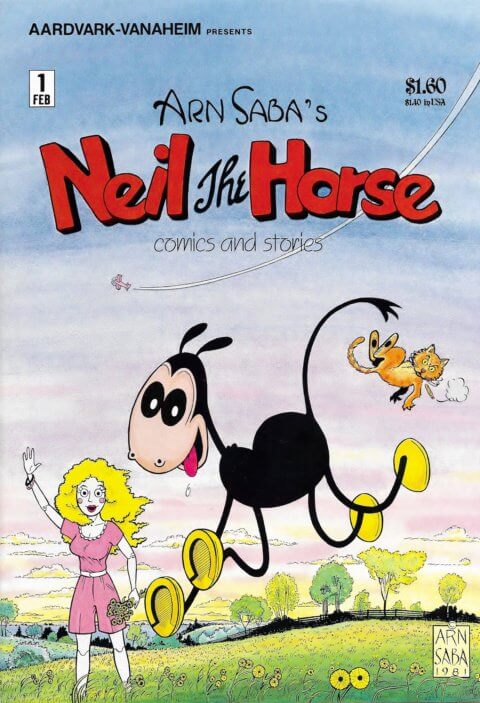

With the emergence of Nelvana in 1971 and the rapid growth of Sheridan College as a premier animation school (which would become a feeder school for Disney and the major Canadian animation studios), it was inevitable that the school would start to offer courses in comic book creation. It is unclear when the first program focusing on comic books started at the college, but this occurred sometime in the early 1970s. What makes this early era of Sheridan College special in terms of comic book creation is that it managed to procure the talents of several well-known American creators as guest lecturers during the decade and this led to at least five comics published through the school’s Tabloid Press.

The first comic book printed by Tabloid Press was 1973’s The Invader by Will Eisner. This twelve-page, oversized (11” x 16”) magazine featured a brand new The Spirit story. The five-page story was in full colour and the remaining pages of the magazine were blank (with some preliminary sketches). There are several reasons why this magazine is notable: it was the first comic produced by the college and was one of the few new The Spirit comics published after the 1960s. Of greater significance is what led to the comic being published in Oakville in the first place: Eisner created the story with his students while lecturing for one year at Sheridan College from 1972-1973.

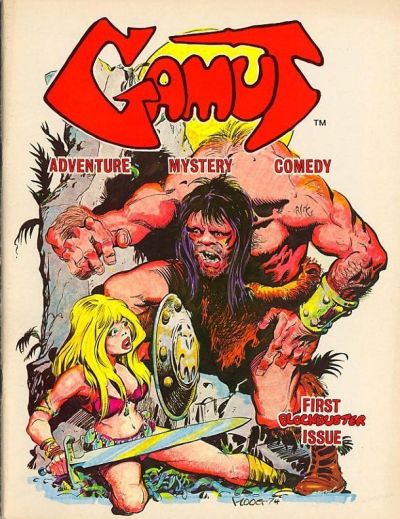

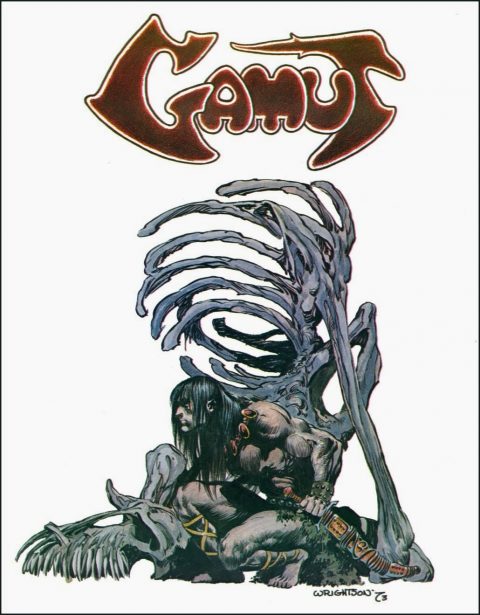

It is not clear if Eisner was the first well-known American comic creator to lecture at Sheridan College, but he certainly would not be the last. Mike Ploog, Neal Adams, Berni Wrightson and Jeff Jones also lectured at the college during the early to mid-1970s. Although Eisner only taught at the college for one academic year, much of the rest of his career turned to teaching, as in 1974 he began a nineteen-year tenure teaching at New York City’s School of Visual Arts. Although Eisner was no longer part of the faculty at Sheridan College, he continued to be loosely involved in their cartooning program and contributed to the subsequent comic series Gamut, which ran for at least four issues from 1975-1979.

Gamut was a black and white magazine-sized publication that featured the work of students in the cartooning program, as well as work (mostly covers and sketches) by the famous guest instructors who participated in the program. The endeavour was developed by the college’s cartooning coordinator, Walter Hanson. At least two well-known Canadian Silver Age creators who were alumni by the time that the first issue of Gamut was released also contributed to the series: Vincent Marchesano and Jim Craig.

I only own the first two issues of Gamut, which are not numbered. Instead, they were released as yearly editions (similar to annuals). The third issue was released in 1977 and what I believe to be the fourth and final issue was released in 1979. The program was ended after 1979 and no further issues of the series were released. There is some confusion among collectors and researchers as to whether or not there was a fifth issue published. John Bell claims that there were five issues in his book Canuck Comics, but also claims in the book that the series was released in 1975 and 1976 (which is incorrect). After years of searching for an example of the supposed 1978 issue, I have come across no evidence that it exists outside of Canuck Comics. Indeed, the John Bell Collection at Library and Archives Canada does not have an issue from 1978, but includes copies of the other four issues. Until someone produces a specimen of this supposed comic, I will continue to doubt its existence.

Moving beyond this discrepancy, one of the things that makes Gamut a special showcase of student talent is not just the involvement of numerous “American Masters” as lecturers/instructors. Instead, we get a glimpse at some of the impressive comic book talents that were coming out of Sheridan College at this time. The first issue includes a roster of up and coming talent that would work for mainstream companies, as well as producing independent comics in Canada and the USA after graduation. Contributors include standouts such as Paul McCusker, whose work appeared in several Canadian Silver Age works, including Orb, Andromeda and Vortex. McCusker’s work also appeared in The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Star and Owl Magazine. Jim Craig, whose character Northern Light is one of the standout characters from Orb has a story called “The Swinger’s Turn” in the comic and another contributor to the first issue of Gamut, Matt Rust, contributed to every issue of Orb.

Award-winning creator Michael Cherkas also has work in the first issue of Gamut. Cherkas contributed to the final issue of Orb and several issues of Cerebus in the early 1980s, but his best-known comics from the 1980s were published by Renegade Press: The Silent Invasion and Suburban Nightmares. Some lesser-known creators who participated in the first issue of the series include Dave Matthews and Greg Landry.

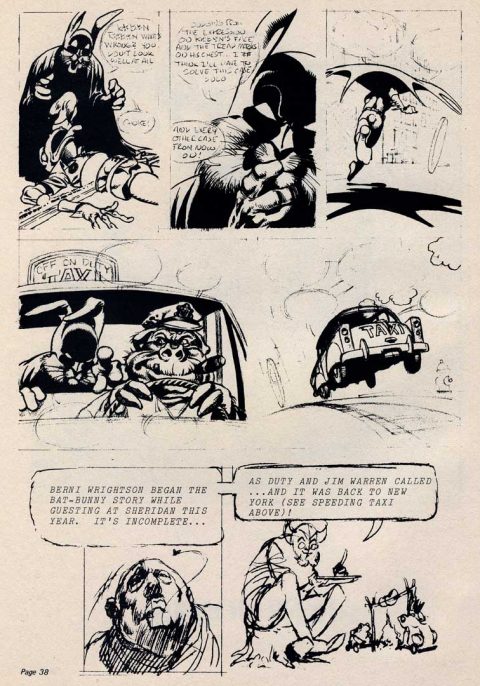

Although artwork by Mike Ploog, Will Eisner, Neal Adams and Jeff Jones appear in the first issue of Gamut, Berni Wrightson is the only instructor who includes original work created as part of the program. A couple of Wrightson’s images in the comic had already been used by DC comics in 1973, including one piece of artwork that would be used in Plop # 1 and another that would be used as the cover of House of Mystery # 213. However, his unfinished story “Bat-Bunny” appears for the first time in Gamut.

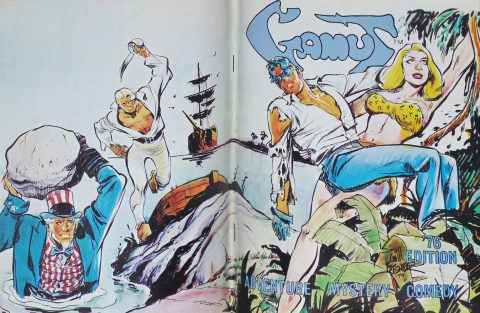

The second issue of Gamut from 1976 sports a beautiful wraparound cover by Will Eisner featuring some of his most famous characters. Michael Cherkas contributes lettering for another story drawn by newcomer Tom Bilinsky (who would later become an artist for Steve Jackson Games’ GURPS Witch World series of RPGs), as well as artwork for a story called “Twin Death” written by Bob Hess. Many of the contributors to this issue are people who I have been unable to identify. Other than Eisner’s cover, the only non-student creation in the comic comes from Vincent Marchesano.

Otherwise, the most notable contributions to this comic from an up and coming talent are two stories by Dan Nosella (one of which is drawn by Bob Smith, who I do not believe is the same Bob Smith who worked for DC comics). Nosella’s career in comic books never really got off the ground (he did work on a Canadian giveaway comic for Kelloggs featuring Toucan Sam in the 1990s). Instead, he would become a successful animator, working for Nelvana in the 1990s and 2000s. More recently he has worked for the Irish studio Brown Bag Productions as one of the directors of the Peabody Award-winning Disney Jr. program Doc McStuffins.

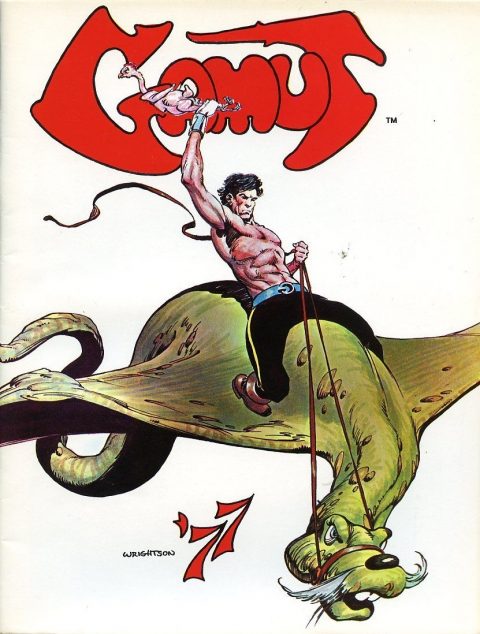

Since I have not been able to procure the 1977 or 1979 issues of Gamut, I do not know at this time who worked on either issue. However, both issues feature covers by Berni Wrightson. The last two issues are much harder to source than the first two that I have profiled this month to the extent that the 1979 issue rarely comes up for sale.

It is unknown how many copies for each issue of Gamut were printed by Tabloid Press. I do not have data regarding the print run of Will Eisner’s The Invader either. That said, the earlier comics published by Tabloid Press are much easier to find than the latter issues to the extent that The Invader is almost always available for sale on eBay and other websites from $20 to $30 CAD. The first issue of Gamut is also relatively easy to find between $25 to $35 CAD, while the second issue also tends to be available for slightly more. A patient collector may be able to ferret out these issues for slightly less. There is also a known error copy of the first issue of Gamut with different colours on the cover. I have yet to see a copy of this error copy come up for sale. The final issues of the series tend to fetch $50 to $100 CAD each. However, given that a copy of the final issue has not come up for sale in some time, it is possible that this estimate is no longer accurate. Either way, sales of these comics are not generally brisk when specimens become available and they tend to languish in sellers’ inventories for some time before finding a buyer. As a final point of interest, this series is not well represented in the CGC census, with only two copies of the first issue being graded (a 9.4 and a 9.6) and only one copy of the second issue having been slabbed (a 7.5). This is not all that surprising for a Canadian publication, but given that the covers feature artwork by famous American artists, I think we may see many more graded specimens down the road.

Ultimately, Gamut is an important series from the 1970s that should be on the radars of Canadian comic book collectors. The four issues, as well as Eisner’s The Invader, are artifacts from the first time that a Canadian educational institute offered a comprehensive program in comic book creation and the fact that Sheridan College was able to attract several famous American comic book artists as lecturers for the program is a fun part of the history of the era. The connection to Orb magazine cannot be understated either. Although I have not covered Orb in my column (yet), the six-issues are a landmark of 1970s Canadian comics and continue to be one of my favourite series from the Canadian Silver Age. Gamut offers a rare glimpse at the quality work being created by students at the time and Sheridan College’s program was part of the development of several creators who would have successful careers in Canadian comics and animation in the decades that followed. If you can find copies of Gamut, I highly recommend picking them up.

Great column, brian. Glad you can throw some light on that pre-Cerebus, pre-Capt. Canuck period. Canadian collectors and comic lovers need to remember that this was a very fertile period in Canadian comic creation and that we couldn’t have gotten to where we are now without it. Prior to the imposed isolation of covid-19 a bunch of us (we call ourselves the Canadian Over the Hill Gang) including me, James Waley, Art Cooper, Vince Marchesano, Ron Kasman and Mark Innes, along with newbie members Walt Durajlija and Allen Sant tried to make a habit of getting together for an extended lunch and the topic of Sheridan and ORB come up regularly.

I agree Ivan…a very interesting and informative article Brian. Thank you

Great informative piece brian, thanks.

The only reason Ivan and the boys let me into the Over the Hill Gang is they need someone to go up and fetch them water.

Yeah, Walt…. You’re the only one not in a wheelchair!

Thanks for chipping in, Ivan, Dave and Walt. Much appreciated. My apologies for not responding right away. We decided to take a couple of days away from the internet to recharge and get some stuff out of storage. Back in the saddle now!

I agree, Ivan, that this era of Canadian comics is quite fertile. The scene across Ontario’s largest cities was quite strong during the 1970s and 1980s, with the work that Vincent and Art produced under the Spectrum name setting that stage and James’ work with Orb being one of the truly important pre-Cerebus/pre-Captain Canuck publications to come out of Ontario during the 1970s. Orb is such a solid publication and I am happy to own every issue except for the illusive # 2. Ron’s “The Tower of Comic Book Freaks” is a great read, but I have yet to take a look at his earlier stuff (such as his contributions to Quadrant). I haven’t had a chance to look at much of Mark’s stuff, but Blind Bat Press is definitely on my radar. It would be fun to be a fly on the wall during a meeting of, as Walt put it, “The Over the Hill Gang.”

Walt, I have a hard time believing that all of these men are only drinking water!

Cheers,

brian

Hey brian

You can also check out more of the written work of Ron Kasman and Paul McCusker in the anthology Growing Up With Comics from Desperado. It’s also interesting to note that Paul was a court artist during the Paul Bernardo trial.

I believe the Bob Smith you mention was at one time an inker on some of Gene Colan’s work at Marvel.

This was one of your best posts yet! I just wish I could find my copies of Gamut somewhere in the hell that is my filing system.

cheers, mel

Good to hear from you, mel, and thanks for your comment. I hope that you have been doing well during the pandemic. Thanks for suggesting Growing Up With Comics. I’ll check it out.

You might be correct about the particular Bob Smith that you mention, but I was unable to delve into this prior to submitting the article. There is at least one other Bob Smith (James Robert Smith) who also worked in comics and who also worked on material that Berni Wrightson contributed to (a short-lived series called “Asylum”). It’s entirely possible that the Bob Smith you mention is the one who worked on Gamut, but I wonder if the Gamut Bob Smith is a third person. I certainly know what it feels like to have a common name. I will have to regale you with some stories about my encounters with other people named Brian Campbell at some point.

Hey brian

Funny you should mention name confusion. The brother of the Bob Smith who worked with Colan is a local artist here in Waterloo County. Some time ago he legally changed his name to John Rula, since the name John Smith tended to cause friction with the authorities who thought he was making it up or being a smart ass.When a cop asks you your name, you don’t want to have to say “John Smith.” When next I see him, I’ll see if I can find out if his brother is the Gamut Bob Smith.

cheers, mel

Further to name confusion: I woke up one morning to the newspaper headline “Mel Taylor dead at 56.” Thankfully it was the drummer from The Ventures. Well, maybe not “thankfully” for him. My old man always used to read the obituaries, he said, just to make sure he wasn’t in them.

cheers, mel

5

Bob Smith, ah yes, he was the artist that designed the store bags for Now and Then comics. A nice graphic of owner Harry Kremer in a space suit in the center. If there were some way to include an image here with the comments I’d share it.