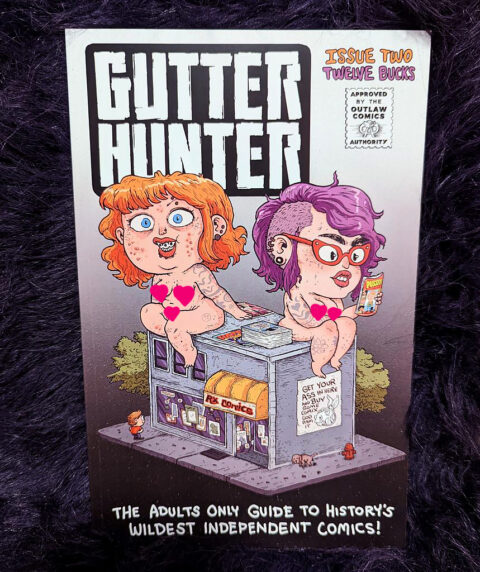

Before getting started on this month’s topic, I want to direct readers to Robin Bougie’s recently published Gutter Hunter # 2. Note that this Canadian publication is NSFW and Bougie calls it “The adults only guide to the history’s wildest independent comics.” In many ways, what Bougie is doing is similar to what I envision for Forgotten Silver, only with a focus on adult and independent comics. Long time readers of this column will recognize that I spoke about Bougie recently, when I returned from my hiatus late last year. At the time, Bougie had just released the first issue of Gutter Hunter, which was something of a logical successor to his long running series Cinema Sewer (which ended with issue # 34 and follows a similar format).

Gutter Hunter # 1 sold out in less than a week and was critically acclaimed. Bougie approached me shortly before the first issue dropped, asking permission to reprint some of my material for issue # 2. I read the first issue over two days (it was a tour de force) and promptly gave him permission to reprint some of my material. When Gutter Hunter # 2 was released last month it included part of my column from February, 2021, “Comic Legends and the End of an Era.” I am quite pleased with the final product and really enjoyed reading Gutter Hunter # 2. Like the first issue, it covers a wide array of bizarre adult and independent comics, boasts interviews with several creators and gets into some little-known stories about the history of independent comics. There is also quite a bit of Canadian content in this 100-page fanzine, in addition to my own contribution. The issue is near and dear to me because it is the first time that any of my comic research has been physically printed.

Gutter Hunter # 2 has been selling well, but there are still copies available at the (NSFW) Cinema Sewer Store. There are also copies of the reprint of issue # 1 available. I personally consider this to be the most important comic fanzine being published in Canada right now, so if you are interested in the subject matter, please consider picking up one (or both).

So, with all of this in mind (and following up on last month’s column where I presented a broad overview of the emergence of Canadian comic book fandom), let’s take a look at an important cog in the history of the Canadian Silver Age: that is, the emergence of comic book fanzines in Ontario in the late 1960s.

As I showed last month, fanzines were first developed as part of science fiction and fantasy fandom and there were numerous such fanzines published in Canada prior to the 1960s. These publications would serve as something of a template for the comic book fanzines that emerged in North America in the 1960s. In Canada, the first comic fanzines were published by George Henderson through Memory Lane.

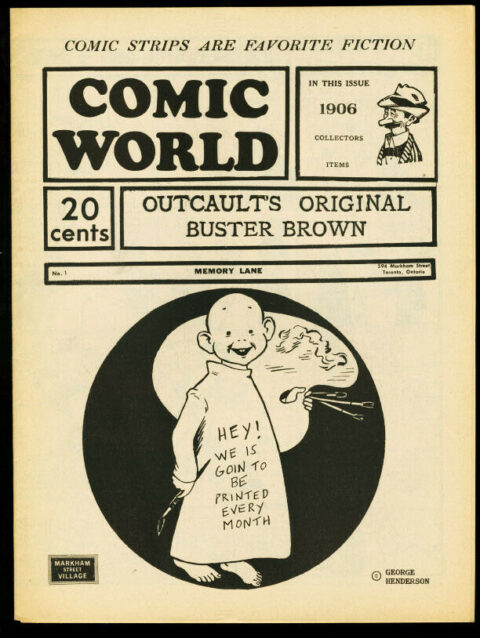

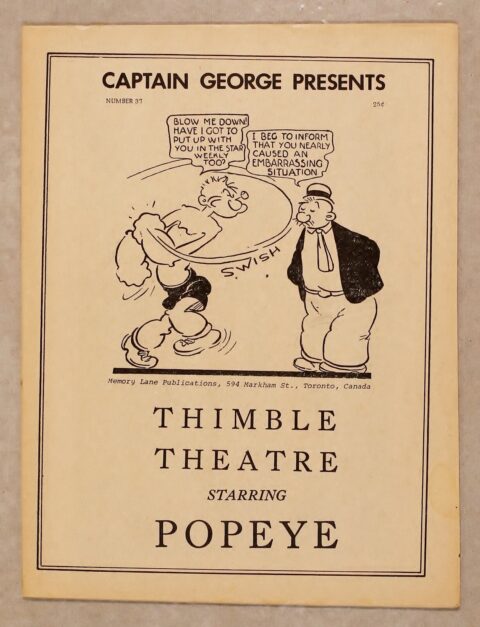

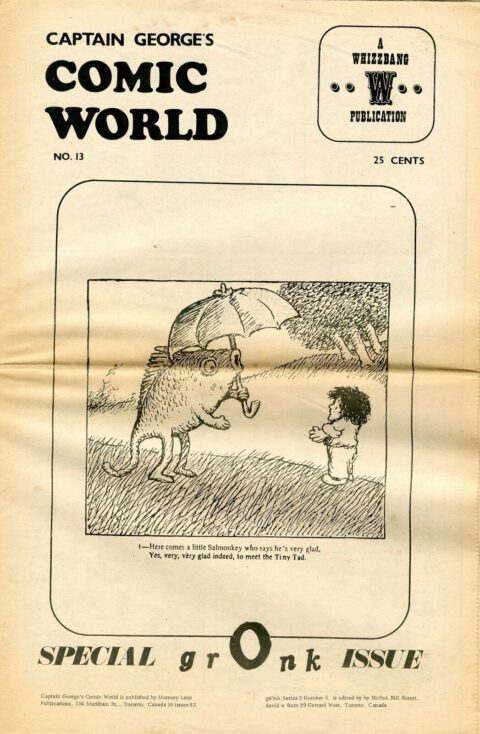

As the Memory Lane comic shop grew a loyal clientele and events like Com-Ex and Toronto Triple Fan Fair increased his profile, Henderson was simultaneously building a mini publishing empire under the Memory Lane Publications name. His first fanzine, Comic World debuted in 1967 and focused on reprinting old, public domain comics strips from the early 20th century such as “The Yellow Kid.” In 1968, the series was retitled Captain George’s Comic World. It underwent another name change in 1969 when it became Captain George Presents. The three series was published on newsprint and released in either newspaper or tabloid form from month to month. On occasion issues would be released as double issues (with double numbering) such as Captain George Presents # 31/32, 33/34, 38/39 and 43/44. Memory Lane also printed the one-shot Marvel Checklist in 1968 in conjunction with Stan Lee’s appearance at Triple Fan Fare. The fanzine boasted that it was “computerized at the University of Toronto.”

The series came to an end in 1972 when Henderson was fined over $4,000 for copyright violations after King Features received an injunction against Memory Lane. Henderson thought he had been carefully reprinting only comics and strips that were public domain, but ended up in hot water because of reprinting material that was still under copyright. After the King Features debacle, Memory Lane stopped reprinting comics and comic strips.

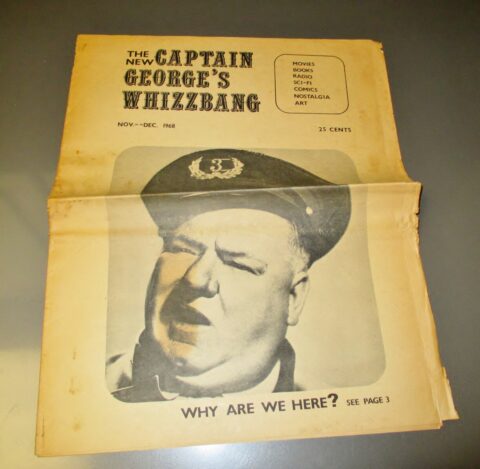

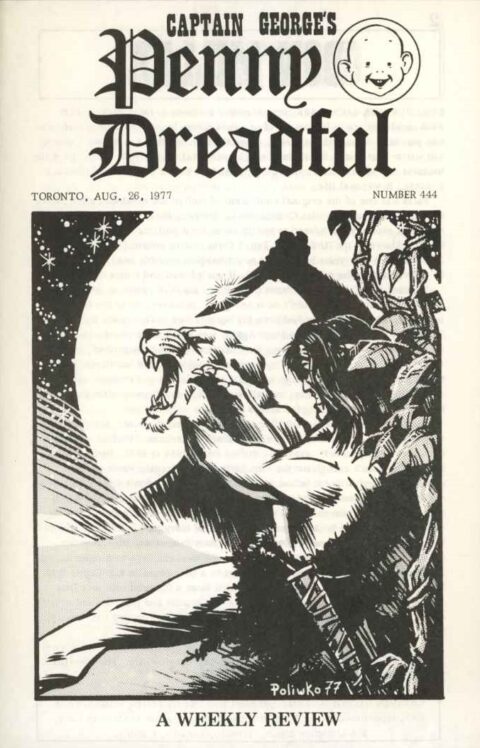

Two additional fanzines debuted in 1968: Captain George’s Whizzbang and Captain George’s Penny Dreadful. Whizzbang was more of a general interest pop culture magazine that covered several different genres and media (with early covers highlighting seven overarching themes: movies, books, radio, sci-fi, comics, nostalgia, and art). Indeed, the series has a similar feel to the science fiction fanzines that preceded it in Canada and the USA, which were undoubtedly an influence on Henderson and his contributors. The series was published infrequently and ended in 1974 with eighteen issues.

Captain George’s Penny Dreadful was actually Henderson’s most successful and longest running fanzine. However, due to its subject matter, it is often overlooked by comic book collectors. This 4-page weekly review saw contributors opine about the latest television shows, movies, comics, paperback books and so on, while often sporting cover art by a fan artist. The series lasted for over six hundred issues and ended c. 1982. Unfortunately, I do not have any images of issues from the 1960s. That said, this is a series that is ripe for a large research project.

The majority of Henderson’s fanzines are relatively inexpensive on the secondary market because they had large print runs and were sold out of his store. I have several issues of Comic Book World and they are interesting historical artefacts, though I do not consider them to be particularly collectible. That said, they are the catalyst for what would come.

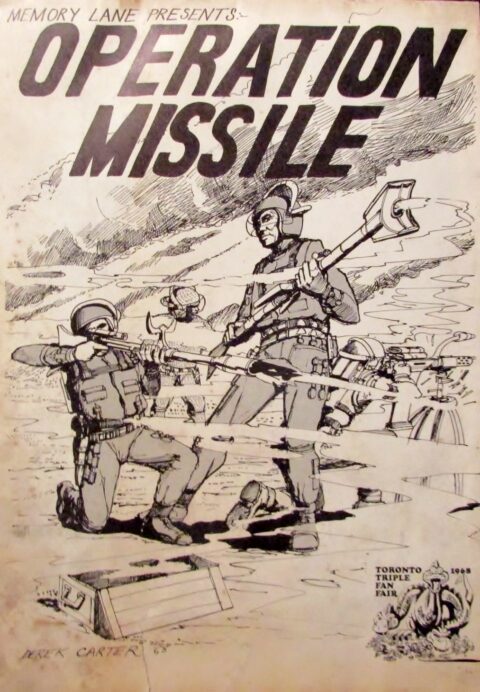

In my opinion, the most important thing that Memory Lane printed during the late 1960s was its sole original comic book: Derek Carter’s Operation Missile, which was published in 1968. Unlike the other fanzines published by Memory Lane, this comic is quite difficult to find and is expensive on the secondary market. Carter had worked on Rocket Robin Hood and was one of the early members of the Ontario Science Fiction Club (OSFiC) that was originally organized by Henderson and played a major role in bringing Fan Fare and Torcon to life. Carter was one of the major fan artists that contributed to the fanzines that the OSFiC would put out during this era, but Operation Missile was his only fully fledged comic.

What makes Operation Missile important is that it was the first comic book (other than giveaways published by Orville Ganes) with original material to be published in Toronto since Bell Features and Anglo-American went out of business during the Canadian Golden Age. It also stands out because it differs from the types of stories that were emerging in other parts of the country at the time. During the late 1960s, creators in British Columbia were starting to put out underground comics that were heavily influenced by the California counterculture scene. Elsewhere, in Quebec, creators were unshackling themselves from the dominance of Fides and the catechetical comics that dominated Quebec during “La Grande Noirceur.” In the Maritimes, Owen McCarron’s Comic Book World imprint continued to be the only major comic creator during this era. Indeed, the Maritimes wouldn’t develop a true homegrown comic book scene until the 1990s (with starts and stops like Old Trout Funnies and Captain Newfoundland), but that’s a story for another day. Meanwhile, the comic scene in the prairie provinces was still a few years away from coming to fruition. Carter’s Operation Missile was a futuristic science fiction war story that didn’t fit anything else that was being published in Canada at the time, but it was the beginning of Ontario becoming the science fiction comic centre of Canada in the 1970s.

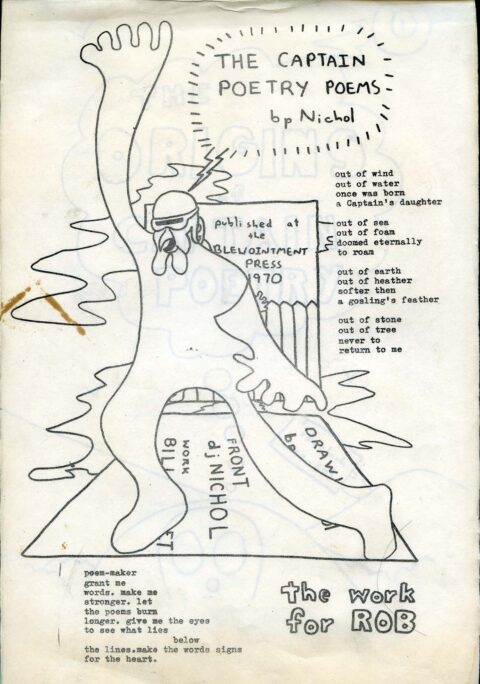

In John Bell’s seminal work on the history of Canadian comics, Invaders of the North, the author identifies concrete poet bpNichol’s 1967 special issue of his experimental magazine grOnk (called Scraptures) as the first comic book fanzine of original material printed during the Canadian Silver Age. Note that Bell and I differ on how we typologize the Canadian Silver Age, as I treat the giveaway era as being part of the Silver Age, whereas he considers it to be a different era altogether.

The work of bpNichol and his publications through his own Ganglia Press are the beginning of one of the most complicated collecting strains in all of Canadian comics. As arguably the key figure in the literary avant-garde comic movement in Canada, the comics of bpNichol do not fit neatly into the trajectory of emerging comic fandom and fanzines in Ontario at the time. That said, even bpNichol would collaborate with George Henderson: Captain George’s Comic World # 13 is also grOnk series 3 # 5. The fact that Henderson and bpNichol collaborated during this period just goes to show how wide reaching that Henderson’s influence was at the time. Despite being associated with poetry and avant-garde literary projects that were of more interest to academics than the general public, bpNichol would continuously return to comics over the next two decades with his own publications (using the Scraptures name again several times, publishing Greaseball Comics and contributing to Snore Comix). Interestingly, he would participate in the Ontario science fiction comic scene in the 1970s by contributing to issues of Andromeda. Eventually, he would write for Canadian children’s programs such as The Raccoons, Fraggle Rock and Blizzard Island before his untimely death in 1988. Someday I will write a column dedicated to bpNichol, the great enigma of the Canadian Silver Age.

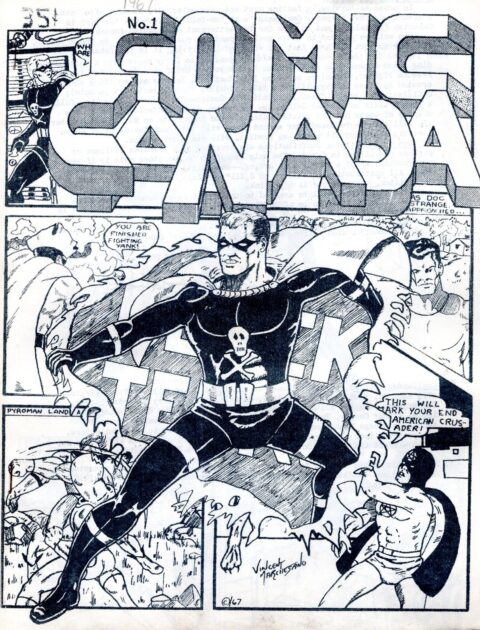

Outside of Toronto, a small but mighty comic scene was developing in Hamilton, Ontario. The very first comic fanzine of the Canadian Silver Age was published in the city in 1967 by Terry Edwards. Edward’s Comic Canada was, unlike bpNichol’s Scraptures, a product of emerging comic book fandom in Canada. This is a fan production through and through with contributors creating new stories around famed characters like the Black Terror (who is featured on the cover, which was drawn by a young Vincent Marchesano).

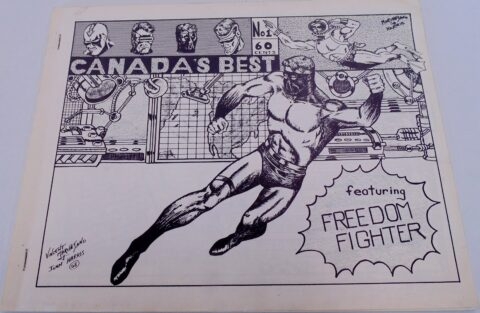

Edwards would publish a second issue, this time called Comicanada, in 1968. These mimeographed fan comics are among the most important comics published during the Canadian Silver Age, as they solidified Hamilton as one of the early hotbeds of Canadian comics and launched the careers of both Vincent Marchesano and Art Cooper. Marchesano would release his own comic in 1968 called The Canadian Comic (which is so rare that I have never seen a picture of one) and 1969 would see Art Cooper’s Canada’s Best Comics also published. Marchesano and Cooper would go on to start Spectrum Publications in the early 1970s, publishing several mini comics and fanzines that are among the most underrated of all Canadian comic books. These two men in particular rarely receive the recognition that they deserve and I have argued in favour of Marchesano’s induction into the Canadian Comic Book Hall of Fame in the past (and I know that I am not alone in doing so). From what I understand, George Henderson would become involved with Terry Edwards in helping to put on Hamilton’s first comic book show, but I cannot say more about this without conducting additional research.

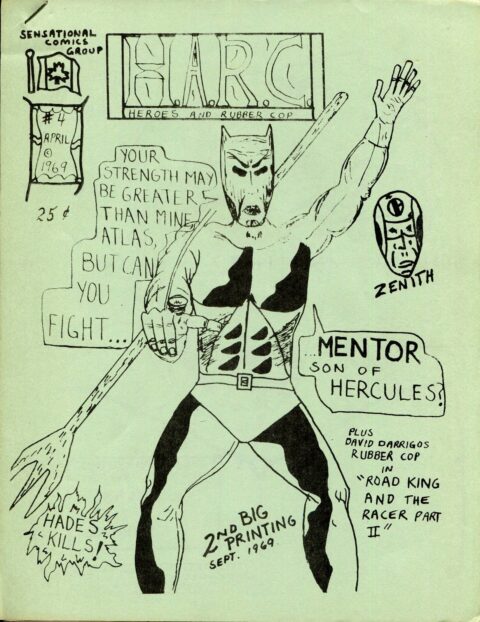

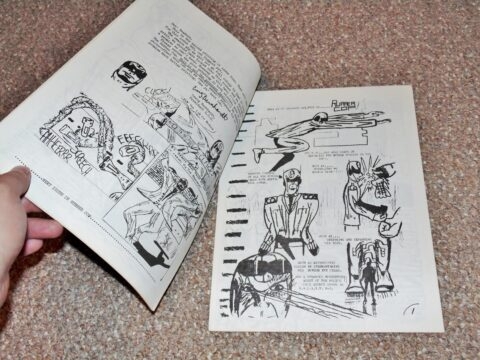

A final Canadian comic fanzine of note that was published in Ontario in the late 1960s is Dave Darrigo and Craig Bernhardt’s Heroes and Rubber Cop. According to John Bell, the first four issues were publishing in Islington, Ontario, with the final issue being published in Marshalltown, Iowa. Darrigo and Bernhardt released the series under the name “Sensational Comics Group” and also produced a comic fanzine called Sensational Display towards the end of 1969. All issues of Heroes and Rubber Cop (sometimes referred to as H.A.R.C.) are incredibly rare to the extent that few people have ever seen a specimen. Early issues were mimeographed with single sided art pages held together by one staple. Supposedly the first four issues had print runs of only twenty to forty copies each. However, issue # 4 (at least) had a second printing that brought the issue to 300 copies with double-sided art pages.

Robert MacMillan offers a concise explanation of the genesis of the series in his entry about Dave Darrigo at his Encyclopedia of Canadian Animation, Cartooning and Illustration. I will paraphrase MacMillan here. Bernhardt and Darrigo were just starting high school when they created Heroes and Rubber Cop. The teenagers had access to a mimeograph through Darrigo’s father’s business and both were inspired to get into business due to Darrigo’s father being a businessman and Bernhardt’s father being a corporate executive. These influences and access to a mimeograph enabled the teenagers to try their hands at a cottage industry of small print run comics. They distributed early issues of the comic fanzine around Toronto, but this was an era where there were virtually no comic shops and they had few places to peddle their products. Eventually they would increase print runs of later issues of Heroes and Rubber Cop and their final comic Sensational Display and attempt to sell them through a mail order business. However, this venture was not successful.

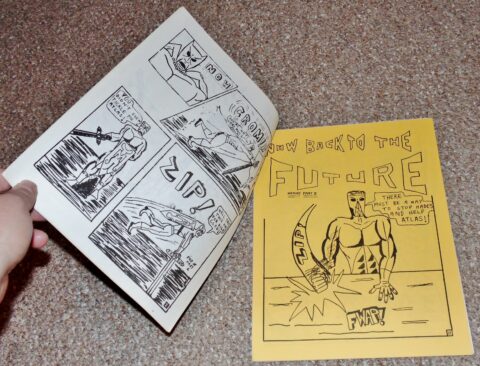

MacMillan is clear that the Darrigo and Bernhardt were highly influenced by Derek Carter’s Operation Missile when trying their hand at creating comics to the extent that the fifth and final issue of the series attempts to mimic the production values found in Carter’s comic. It is also apparent that the teenagers were much more interested in science fiction and superhero stories based on the one issue of Heroes and Rubber Cop that I have in my collection. Of interest is that Bernhardt was responsible for “The Heroes” stories in the comic, while Darrigo was responsible for the “Rubber Cop” stories. The two friends’ product is extremely amateurish and failed to find an audience, but was quite ambitious for its time and is a hallmark fanzine of this era.

Everything came to an end when Bernhardt’s family moved to Iowa due to his father’s job in 1969. Bernhardt had access to a photo-offset press company in Iowa, which is why the final issue of the series was published in Marshalltown. Nevertheless, I still consider issue # 5 of the series to be a Canadian comic.

After Bernhardt moved to Iowa, the teenagers started to drift apart. Bernhardt met another teenager in Iowa, Ron Davis, who was creating his own comics, which Bernhardt wanted to publish. The result was Sensational Display, which Darrigo only contributed to as an editor. The comic was not a success and would be the last released by Sensational Comics Group. Darrigo had been planning to release another comic with his friend Ron Hobbs called Sensational Debut, but due to the failure of Sensational Display the project was scrapped. I am not sure what happened to Bernhardt after this and I suspect that he left comics altogether, but Darrigo would go on to become an extremely important figure in the history of Canadian comics. That, however, is a story for another day.

By the end of the 1960s Canadian fandom was in full swing and Toronto was its epicentre. “Captain” George Henderson was a pivotal figure in the emergence of comic book fanzines in Ontario due to his own publications through Memory Lane and publishing Derek Carter’s highly influential Operation Missile. Both Terry Edwards and bpNichol were doing their own things around the Golden Horseshoe at the time and would eventually collaborate with Henderson. Edwards would help to launch the careers of Vincent Marchesano and Art Cooper who would release some of Ontario’s the greatest comics in the early 1970s. Meanwhile, bpNichol and his associates would eventually put out some of the most complicated and bizarre comics, Snore Comix (that are not really what most people would consider to be comics), through Coach House Press. Ontario was developing its own unique comic book scene and comic book culture with “Captain” George smack dab in the middle of everything. Henderson’s involvement would wane in the decade that followed, but he opened to door for other people to create their own comic fanzines, open their own comic shops and start their own conventions. In the burgeoning Ontario comic scene, the best was yet to come.

Such a great post brian, nice work. Vince Marchesano and Art Cooper are still active in comics, they both frequent the shop and they both contributed to my Canadiana Auction that ended last week, thanks fellas. I too pushed for more recognition for Vince, a few years ago I was on the Joe Shuster Awards Hall of Fame Committee and it had to be three years in a row that I pushed for the HOF for Vince, perhaps Kevin Boyd is reading this and will finally make it official.

Thanks, Walt. I’m glad you enjoyed this month’s column. Perhaps I will have to write a dedicated column about Marchesano and Cooper’s creations through Spectrum Publications sometime soon. I think their work is among the most underappreciated in the history of Canadian comics and they deserve a bigger spotlight.