Happy Thanksgiving everyone! With the Federal election only a week away, I spent quite a bit of time thinking about whether or not I should focus on political comics or environmental comics this month (due to environmentalism becoming one of the major issues of this election). Ultimately, I decided against doing so in favour of taking a look at one of the main subgenres of comics from the Canadian Silver Age that I have, thus far, neglected: bandes desinnées Québécoise (BDQ).

One of the most fascinating parts of the history of Canadian comic books is how they evolved so differently in this country due to bilingualism. There is a breadth of incredible comic books that are released in French in Canada that English speaking audiences are either unaware of or unable to engage in because of language barriers. This is nothing new but is part of the fabric of the history of Canadian comics dating back to the Golden Age.

Golden Age BDQ are something that my esteemed colleague, Ivan Kocmarek, has not dabbled in through his “Whites Tsunami” blog here at Comic Book Daily and the reality is that I can hardly blame him or fault him for not covering these comics. As a person who has spent years highlighting the many WECA era books that were created by Canadians, it is hard to be enthusiastic about French comics that were coming out of Quebec at that time. The market was dominated by Montreal’s Fides, which started publishing translated reprints of the American comic series Timeless Topix (later just Topix). These Catholic comics were created by the Catechetical Guild Education Society and aimed to counter the “unwholesome” influence of America’s other types of comic books during the 1940s.

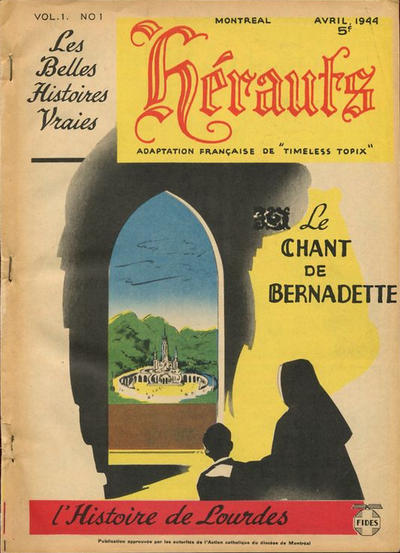

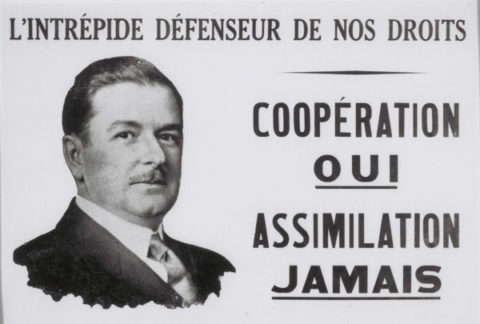

Fides’ domination of the French comic book market in Canada lasted for over twenty years. The first issue of their translated Timeless Topix comic, Hérauts, was released in April 1944. This was late in the WECA period and apparently these wholesome translated comics did not face the same hurdles as the many comic books that were banned from importation into Canada at the time. In fact, the provincial government in Quebec, led by Premier Maurice Duplessis from 1936-1939 and again from 1944-1960 (Duplessis died in 1959) helped to foster the success of companies like Fides. The Duplessis government’s party, Union Nationale, was closely linked to the Roman Catholic Church and the party enacted policies that favoured the church. Historians have come to call this era of Quebec politics “La Grande Noirceur” (translated to “The Great Darkness” in English).

Union Nationale lost to the provincial Liberals shortly after Duplessis’s death, leading to the secularization of government institutions and power being stripped from the church as part of the Quiet Revolution. Nevertheless, the party was re-elected in 1966. The party became increasingly fractured in the late-1960s because of disputes amongst members who supported either federalism or nationalism, leading to competing conservative political parties, as well as an electorate that was undergoing a cultural shift as part of the Quiet Revolution. The party was defeated in 1970 by Robert Bourassa’s Liberals, as conservative voters split their votes between Union Nationale, and the newly founded Ralliemont Creditiste and Parti Québécois. Union Nationale would never hold power again. By the early 1980s, the last remaining members of Union Nationale had either joined the federal Progressive Conservative party or the provincial Parti Québécois.

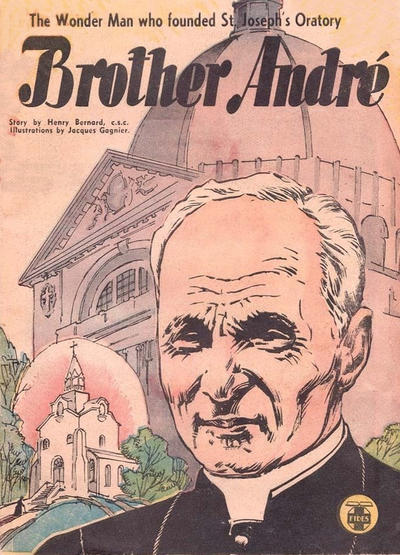

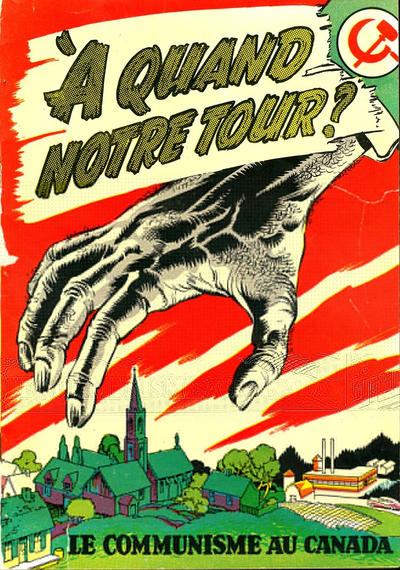

Hérauts lasted for two hundred thirty-four issues and ceased publication in 1965, coinciding with the decline of the Roman Catholic Church’s power in the province and the rise of the Quiet Revolution. Regardless, Fides was the last remaining Canadian publisher of comic books from the Golden Age when they closed down. They had also published English language comics on occasion, such as their reprint of the anti-communist comic Is This Tomorrow? (which they also released in French as À Quand Notre Tour?) in 1947 and perhaps their only home-grown full-length comic, Brother André, in 1955 by Henry Bernard and Jacques Gagner. From 1955-1960, Fides experimented with publishing comics stories by local talent in Hérauts and its comic series for younger readers, Les Petits Hérauts, beginning in 1958. However, by 1960, the company had reverted to publishing only reprints.

It is difficult to place any of the comics released by Fides into the established canon of WECA (or even FECA) material that Ivan Kocmarek and numerous collectors have spearheaded over the years. It is also difficult to situate Fides into the Canadian Silver Age, as it is the only real holdover from a different era that leaks into the era that I research. Perhaps it is necessary to position French-Canadian comics from 1944-1965 as being their own, distinct branch of collecting and research due to it being the comic book manifestation of the relationship between Union Nationale and the church. Indeed, this era was “La Grande Noirceur” of Canadian comics.

Since we started researching Canadian Silver Age comics, BDQ has been something that Victor Marsillo and I have been dabbling in separately due to this particular collecting stream being outside of Dan’s realm of interest. None of us are fluent in French. I have a working understanding of the language that was a requirement for completing my Ph.D., but reading and writing the language (let alone speaking it) remains a struggle for me. As such, trying to identify, collect and research BDQ has been both fun and daunting for Victor and myself. It is also the area of my master list of Canadian Silver Age comics that likely has the largest number of unintentional omissions. That said, we certainly have uncovered enough information about this era to provide a road map/starting point for collectors interested in this particular collecting stream.

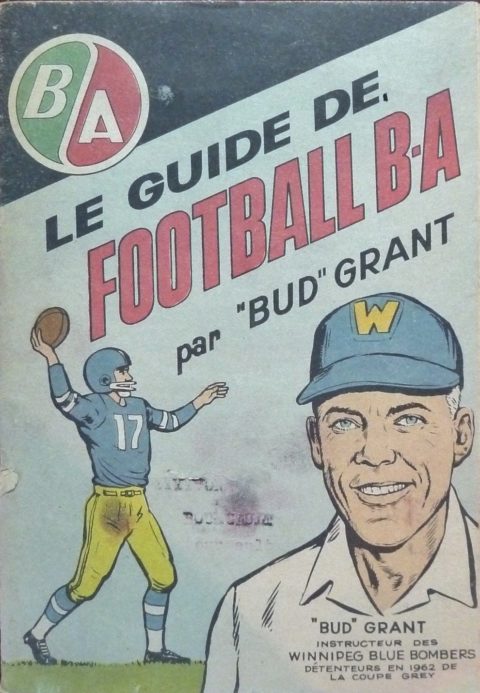

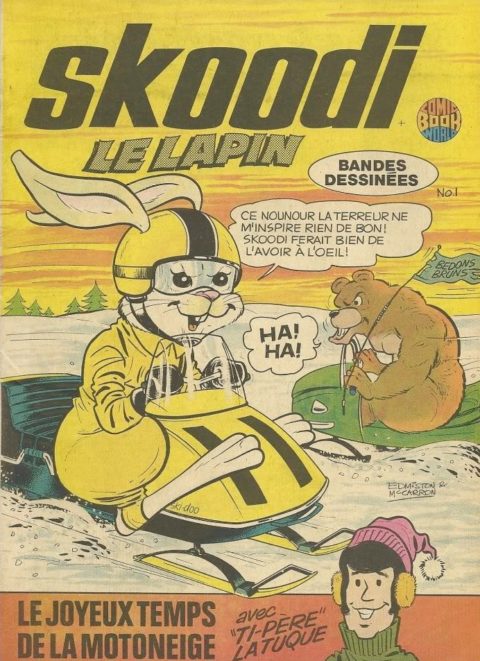

Outside of Quebec, Canadian comics from the early to mid-1960s were almost entirely giveaways commissioned by businesses, NGOs and various levels of government. The era was dominated by Toronto’s Ganes Productions, operated by Orville Ganes. Halifax’s Comic Page Features (later Comic Book World), operated by Owen McCarron, entered the scene in the mid-to-late 1960s. Both companies would occasionally release French editions of their comics depending on the needs of a particular client. For example, some of Ganes’ earliest mini giveaway comics for BA and Coca-Cola were distributed in French and English versions. McCarron, likewise, released several comics that targeted the province of New Brunswick in French and English editions too, such as Skoodi the Rabbit (reprinted as Skoodi le Lapin) for the Ski-Doo company and Captain Enviro (reprinted as Capitaine Enviro) for The Committee of Atlantic Environment Ministers in 1972. Other giveaway comics were also released in French during the 1960s and early 1970s, including a reprint of Malcolm Ater’s American anti-smoking comic Where There’s Smoke (reprinted as Il n’Ya Pas de Fumme) which were repacked by the Canadian Cancer Society, as well as Bobby Cooper from sports equipment manufacturer Cooper-Weeks in 1966.

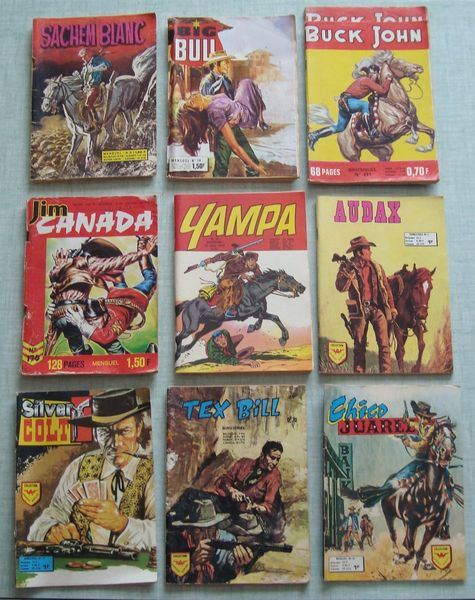

Of course, American comics were available in Quebec after the end of WECA, just like in the rest of Canada. However, unilingual Francophones did not have easy access to American comics, due to a lack of translated material on the market in Quebec. This changed in the late-1960s with the creation of Les Éditions Heritage, which started publishing reprints of both Marvel and DC comics, prior to releasing its own Quebec created comics in the 1970s (which is a story for another day). Prior to this, Francophone readers who were looking for something different from the religious comics produced by Fides had to look to Europe for material to consume. Franco-Belgian comics such as Asterix, Tintin, Spirou and Pif gained mainstream success or renewed attention in Quebec during the 1960s and had an indelible effect on the new generation of comic creators who started working in comics in the province in the late-1960s. 1964 also saw the publication of Jean-Claude Forest’s Barbarella comic strips in book form for the first time, which is a hallmark of the era and gained mainstream recognition in North America due to the Jane Fonda movie adaptation released in 1968. These Franco-Belgian comics were not printed in the same way that North American comics (grand format) were, being released in “Album” format, with other popular titles sold in formats similar to what we would consider digests (“petit format” or “bande dessinée de poche”) in the rest of North America.

Additionally, as the Quiet Revolution continued in the province, the counter-culture movement was taking hold in the United States and elsewhere in Canada, leading to the emergence of Underground Comix. Despite the language barrier for unilingual Francophones, the works of Robert Crumb and Gilbert Shelton became particularly popular on university campuses throughout Quebec. With the province undergoing massive cultural changes that occurred simultaneously to different cultural changes across North America that affected cultural consciousness, critical and potentially subversive artistic projects began to proliferate in Quebec as part of the province’s growing counterculture movement.

In 1968, BDQ started to undergo a massive change and comic books in Quebec have never been the same. It was during this year that a small group of creators started working together under the name “Chiendent” (translated to “Grass” in English) started publishing strips in Montreal newspapers La Presse and Dimanche-Magazine. Members included Jacques Hurtubise (aka Zyx), Réal Godbout, Gilles Thibault (aka Tibo) and Jacques Boivin, all of whom played crucial roles in the success of BDQ in subsequent decades, from their roles in early-1970s BDQ such as L’Hydrocéphale illustré, La Pulpe and B.D.to Hurtubise’s involvement in the creation of Croc magazine and Godbout’s famous Red Ketchup character.

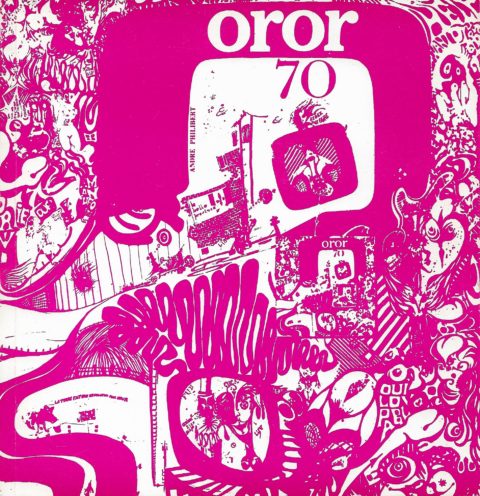

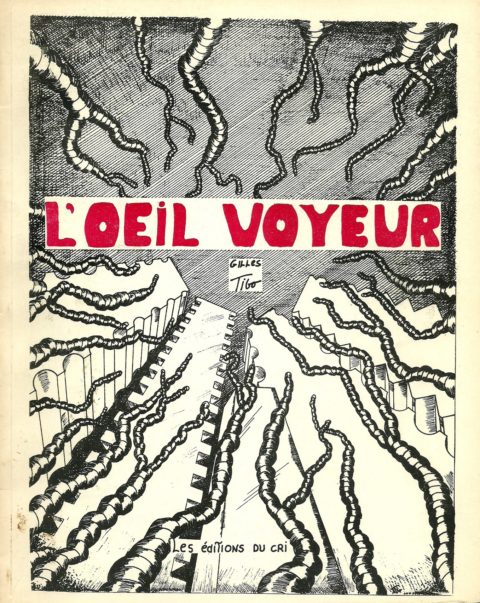

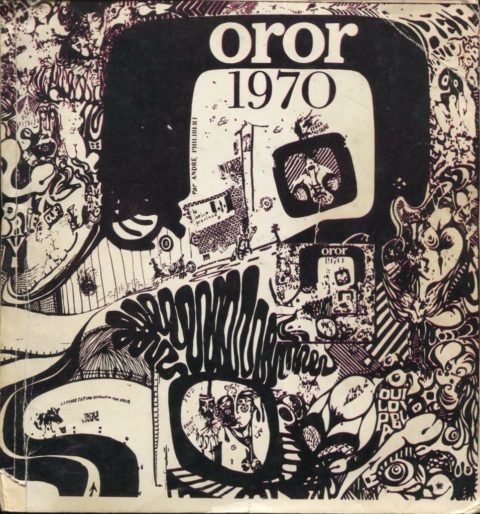

It was André Philibert whose one-shot comic Album ushered in what is now referred to as “Printemps de la BD Québécoise” (or the springtime of Quebec comics). 1970 saw the release of the first two comic books released in Quebec by Francophone creators during the Canadian Silver Age. Both were released by Les Éditions du Cri, a short-lived book publisher based in Montreal, in the Album format popularized by Franco-Belgian comics of the era. Philibert’s comic Oror 70 (Celle qui en a marre tire) (roughly translated as “the one who is tired”) is a psychedelic countercultural narrative that focuses on free love, drugs and a rejection of consumerism. This was followed by Tibo’s L’Oeil Voyeur in December, 1970. Tibo’s comic follows the strange, psychedelic adventures of a stick man with an eyeball for a head. According to noted BD historian Sylvain Lemay’s doctoral thesis, a third title from Les Éditions du Cri called Baboune was in the works. However, I have not been able to find any additional reference to it and am not sure that it was ever released.

Both Oror 70 and L’Oeil Voyeur are incredibly scarce today. Oror 70 had a print run of 1000 copies. Philibert released a reprint, completely in black and white, in the 1990s are part of Woodstock en Beauce, a music festival held in St-Ephrem-de-Beauce, Quebec that started in 1995 as an homage to the original Woodstock. Woodstock en Beauce continues to this day as an annual event. The second edition of Oror 70 is just as scarce as the original, having a matching print run of 1000 copies. The original and reprinted versions of the comic rarely come up for sale and can fetch several hundred dollars each at auction. I own an original, which I was fortunate to acquire from a rare book dealer in Quebec for under $40 CAD in January 2017.

I do not have accurate print run information for Tibo’s L’Oeil Voyeur. However, I suspect that Les Éditions du Cri published around the same number of copies as it did for Oror 70. Sourcing a copy for my collection was a daunting task and even finding an image of the cover eluded me for over a year after I learned of the comic. Victor was able to find an Amazon dealer who had two copies available for sale and I was able to purchase a copy in late 2017 for $42 CAD. I have not seen another copy of this comic come up for sale since, so it is difficult to estimate what a copy might sell for at auction today.

Although Les Éditions du Cri’s BDQ output was short-lived, Philibert and Tibo would play pivotal roles in the development of BDQ during the Springtime of Quebec Comics. The first half of the 1970s was an era of BDQ that established the medium in Quebec for decades to come and includes unrivaled output in Canada in terms of the Underground Comix genre. Next month, I will take a closer look at the key players and titles from the Springtime of Quebec Comics and their continued legacy.

What a thoroughly fascinating exploration of our French culture in comics. Wouldn’t the ones released in the mid 40s be considered WECA? Why would WECA only be limited to English comics when it was supposed to represent all Canadian output released as a result of the ban on American comic imports?

Klaus, thanks for your comment. I am not sure that the comics released by Fides neatly fit into the criteria for WECA for two reasons. First, they were published late enough during the era that they might be better considered as transitional, which is something that Ivan has discussed regarding English comics. Second, it is not clear that the comics that Fides published were ever subject to WECA (some “wholesome” printed material was exempt). More research is needed and your second question is one that I have wondered about during my own research and collecting.

Klaus, you raise excellent points and brian, you’ve done a commendable job of looking into the Quebec comics from the past. Klaus, The exclusion of Herauts from my examination of the WECA period in Canada was a result of two things but one of them wasn’t a conscious neglect of comics produced in Quebec during this period. First it was hard enough to dig out what could be dug out of the WECA period in English Canada and all my time and effort on the project was devoted to this. Second, I just didn’t know enough about the production of comics in Quebec especially during the Second World War. A just examination of those comics would have entailed travelling to Quebec many times to examine archives and interview people and I have neither the time nor funds to do this. This has to be left to future investigators. These Herauts were indeed comics published in Canada during the WECA period but I don’t believe their inception and mandate had anything really to do with WECA restrictions (I’ll happily listen to arguments to the contrary). I have a few of these WWII issues of Herauts and my understanding is that they are reprints and translations of American Topix comics which were produced by the Catechetical Guild of St. Paul, Minnesota. I see them not so much a product created out of the economic necessity to block American comics from coming into Canada but more out of a linguistic and proselytizing concern. Take a look at the sub-heading under the Herauts title in the graphic of the cover of the first issue that brian has put up. It states that these books are adaptations of Topix comics. Nevertheless, they should be accounted for in any survey history of Comics in Canada during WWII and any history of Comics in Canada in general. Your points are well-taken, Klaus.

Thanks for your comment, Ivan. Your explanation here is in line with my own assumptions about Fides and I mention some of the points you make in this article. Thank you for taking the time to clarify these points. Of course, there is a great deal that we do not know about this era of Quebec comics and I consider researching them to be quite daunting. Fides is, perhaps, so different from the established eras that it might be best to think of its output as its own distinct era of Canadian comics.

On a different note, I wonder if you can shed some light on this: I believe that there were some American comic series that were exempt from WECA. Is this the case? Thanks again, brian

If there is a publisher that was indeed given an exemption to print and distribute US comics in Canada I would say Standard/Better/Pines fits that description.

They printed books at 36 Toronto Street pre and post 1946 under various indicia. Publication Enterprises Ltd.,Better Comics of Canada etc.

I think they were able to do this because they were a pre-existing Branch Plant subsidiary of US owners in the pulp and paper industry in Canada.

It was a strategic product that US companies had investment in and the export of the pulp and paper products to the US helped our fragile economy during World War 2.

Great text. If you give me your email, I can send you a pdf of La Baboune (1969).

[email protected]

Thanks for mentioning Pines, Standard and Better, Jim! These definitely fit the bill in terms of FECA (at the very least). I was thinking about earlier stuff, but my memory was playing tricks on me. This morning, reading Ivan’s most recent column, I had an “ah-ha” moment when I noticed his short discussion of how comics like Calling All Girls and True Picture Magazine were sold in Canada. These were the titles that I was thinking of. That said, I am not sure if these were imports or if they were actually printed in Canada.

Thanks, Sylvain, for reaching out. PM sent.

Correction: In this column, I erroneously state that, in reference to the Chiendent group, “Members included Jacques Hurtubise (aka Zyx), Réal Godbout, Gilles Thibault (aka Tibo) and Jacques Boivin.” I want to apologize to readers for this error, which I only noticed recently and was a result of last-minute edits that I was making before submitting the article for review. In reality, the Chiendent group included poet Claude Haeffely and illustrators André Montpetit, Michel Fortier and Marc-Antoine Nadeau. Despite only producing strips for approximately six months (and producing several comic albums that were never published), the Chiendent group helped to free BDQ from its catechetical trappings and set the stage for the abovementioned creators who I erroneously claimed were members of Chiendent to embark on their own journeys as comic creators.