Since starting Forgotten Silver here at Comic Book Daily, I have had the pleasure of writing a topic-oriented column from time to time. As I sat through Halifax’s second heat wave of 2020 (which lasted over two weeks), it dawned on me that it had been some time since my last column of this type: the connection between Canadian Silver Age comics and vinyl record collecting last November. This heat wave got me thinking about the plethora of environmental comics that were published in Canada throughout the 1960s and 1970s which, for all intents and purposes, represent two distinct collecting strains within the Canadian Silver Age.

Initially, environmental comics were a common part of the Giveaway Era, before taking on new meaning and emphasis during the Underground Era. During the Giveaway Era, such comics emphasized land stewardship, management, and conservation by emphasizing individual responsibility as a civic duty, while also promoting the importance of preserving the environment for the benefit of industry. The underground comix that followed presented a different discourse, amplifying anti-corporate and anti-government sentiment based on perceptions that governments and corporations were failing to be good environmental stewards. Since there are a plethora of these types of comics from the 1960s and 1970s, I will cover this topic over the next two months. This month I am going to delve into the environmental comics from the Giveaway Era before returning to the Underground Era in September.

It should come as no surprise that the two major giveaway companies that propelled the early Canadian Silver Age, Toronto’s Ganes Productions (operated by Orville Ganes) and Halifax’s Comic Page Features/Comic Book World (operated by artist Owen McCarron and writer Robin Edmiston), produced numerous comics with environmental themes. The earliest of these comics were published by Ganes Productions and emphasized safety and/or land management. Ganes’ environmental comics from the early to mid-1960s are representative of the agendas of the various government agencies that contracted the company at the time. This is also true for the Comic Book World comics that came in the late-1960s and into the 1970s, even though government policies and agendas had changed. Another key difference displayed in the comics published by the two companies was their storytelling and artistic styles. Whereas Ganes’ comics had a more serious tone and appearance, the comics created by McCarron and Edmiston were cartoonish and whimsical by comparison.

Perhaps the first environmental comic published in the Silver Age was Ganes’ Our Forest Lands, which was released in 1963 through the Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. This Ontario-centric educational comic presents a narrative that would dominate the environmental giveaways of the era insofar as conservation and environmental stewardship is presented as being imperative for the functioning of industry. The comic, which is narrated by a fictional park ranger, explains that Ontario’s forests are filled with natural resources that must be conserved and managed properly for the continued success of various industries, including the lumber industry, the importance of water for power generation and domestic needs, as well as leisure industries such as hunting, fishing and camping. The message is clear that Ontarians have a responsibility to preserve the land and its resources in the present (as shared, common property) and for future inhabitants.

This narrative continues in Ganes’ 1965 For Future Generations: The National Parks of Canada, which was published under the authority of Arthur Laing, then the federal Minister of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources. Both of these comics focus on land stewardship and management as part of a governmental agenda concerning protecting flora and fauna as natural resources that need to be preserved for the future.

Ganes published a second comic with the Ontario Department of Lands and Forests at some point during the mid-1960s: A City Boy in the Woods. Unlike the aforementioned Ganes comics, A City Boy in the Woods focuses on woodland safety (particularly the dominant “only you can prevent forest fires” messaging of the era), which is a logical extension of many of Ganes’ other comics from the early to mid-1960s that emphasize issues of health and/or safety.

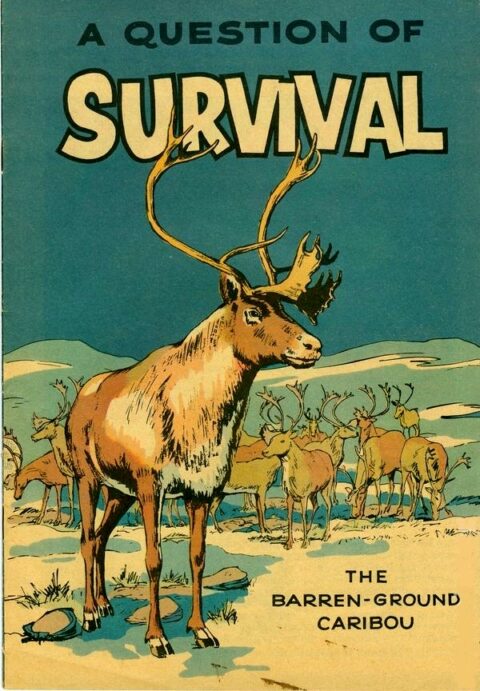

There are two comics released during this period that I am convinced were published by Ganes, but that I cannot verify with absolute certainty. The first, a twelve-page comic called A Question of Survival: The Barren-Group Caribou was released in 1965 through the Canadian Wildlife Service and has the distinction of being released simultaneously with a ninety-two-page book called Tuktu: A Question of Survival by Fraser Symington. The cover has the look and feel of a Ganes publication, but until I have an opportunity to inspect one in person, there is a distinct possibility that this comic was published by someone else.

According to Craig A.R. Campbell’s (no relation) 2003 article, “A genealogy of the concept of ‘wanton slaughter’ in Canadian biology,” published in the edited volume Cultivating Arctic Landscapes, there was a caribou crisis in the Canadian arctic that began during the 1950s that the Canadian Wildlife Service blamed on the “savagery” of, and over-hunting by, Inuit people (then called “Eskimo” by government agencies). Aboriginal hunters, on the other hand, blamed government interventionist policies for the crisis. The resulting comic, A Question of Survival: The Barren-Ground Caribou, is a condescending account from the Canadian Wildlife Service that blames Inuit hunters for their plight. Interestingly, the comic was released in both English and Inuktitut versions. I did not mention this comic in my previous article about arctic comics and issues of representation because I was unaware of its existence at that time. However, its existence means that Super Shamou is not the first or only Canadian comic to be released in the Inuktitut language.

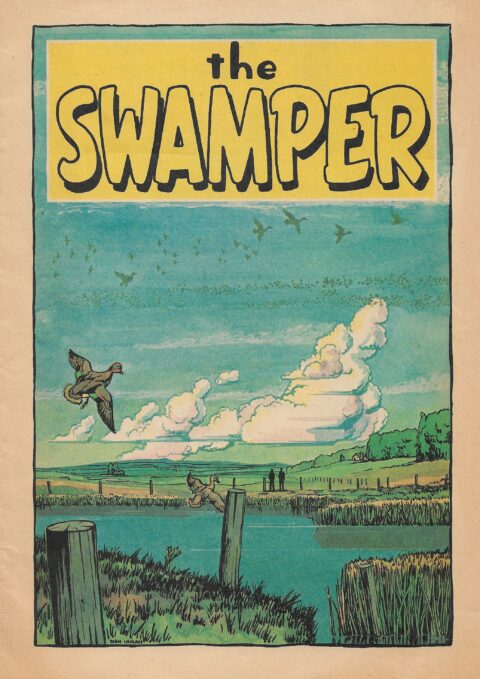

The second comic that may have been released by Ganes is The Swamper. Released in 1964 through the Canadian Wildlife Service, this comic has the look and feel of a Ganes comic, but does not have Ganes Productions noted anywhere (or G Educators, which the company used occasionally).

The Swamper presents a similar narrative around environmentalism to the comics noted above but is told through the eyes of a disgruntled journalist named Cy Hill who is sent to the fictional farming community of Wingsville to write a story about wetlands. Wingsville has a problem with drought and its diminishing number of reservoirs to the extent that the majority of farmers are in trouble. By draining local marshes, the water table has dried up, necessitating the importation of water and leading to the destruction of the soil. One farmer, the eponymous “Swamper” has succeeded where the others have failed by rotating crops and preserving the wetlands to the extent that his land and its natural inhabitants work in symbiosis with his agricultural activities. The take-home message of the comic is that land management needs to be based on conservation in order for industry to succeed.

It is possible that Ganes released additional environmental comics and this is due to the fact that we are still uncovering comics created by Ganes Productions from time to time. As Ganes’ influence on the Canadian comic industry began to wane into the late-1960s, McCarron and Edmiston were gaining momentum with their Comic Page Features and later Comic Book World imprints. The duo released five known environmental comics from 1969 to 1972, all of which were released under the Comic Book World name.

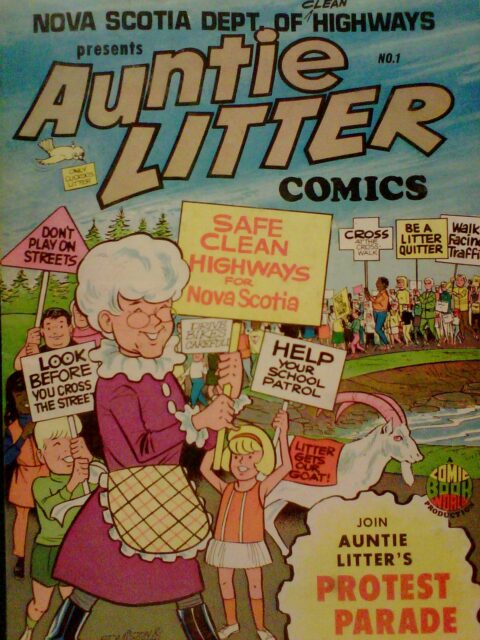

The first two environmental comics published by Comic Book World feature the character Auntie Litter. One of the things that separate McCarron and Edmiston’s work from Ganes is that their comics were always character-driven. Auntie Litter is part of this trajectory, as an embodiment of the intended message that can easily be consumed and understood by children. This is also amplified by McCarron’s whimsical style. By this time, the government discourse around environmentalism had shifted from issues of conservation and land management towards the bogeymen of littering and pollution. This is evident in the first comic featuring Auntie Litter, 1969’s Auntie Litter Comics # 1.

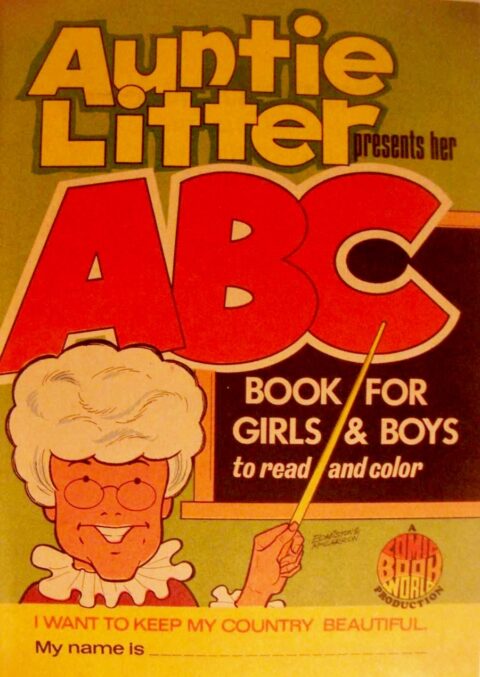

A second comic featuring Auntie Litter appeared in 1970 but with a different name and no longer following the numbering from the first issue. From what I understand, Auntie Litter Presents Her ABC Book for Girls & Boys is a comic colouring and activity book. Unfortunately, despite the fact that I live in Halifax, the comics produced by McCarron and Edmiston tend to be so rare (with a couple of exceptions) that I have not had the opportunity to handle either of the Auntie Litter comics. As such, I cannot comment on them beyond the covers presented here. This is also true for two of their other environmental comics, 1970’s Keep Nova Scotia Beautiful Comics and 1972’s World of Sammy Seagull (the latter of which was produced in collaboration with the Committee of Atlantic Environment Ministers). Both comics are so rare that I do not even have cover scans in my files that I can share. One final note about these first four environmental giveaways from Comic Book World is that McCarron and Edmiston often released French versions of their comics. At the time of writing, I have not found any evidence that this applies to the two Auntie Litter comics, Keep Nova Scotia Beautiful Comics or World of Sammy Seagull. However, it is quite possible (even probable) that French versions exist.

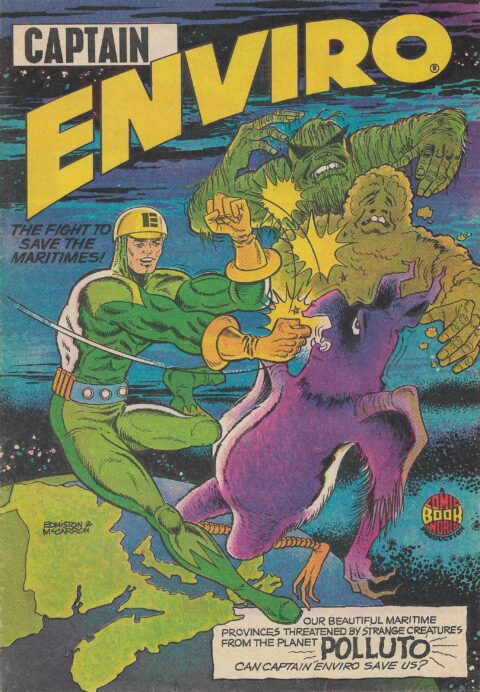

The most desirable of Comic Book World’s environmental comics (at least among collectors) and one of the most coveted comics created by McCarron and Edmiston, in general, is 1972’s Captain Enviro (published in French as Capitaine Enviro). The comic is also discussed in length by Mark J. McLaughlin in his 2013 article, “Rise of the Eco-Comics: The State, Environmental Education and Canadian Comic Books, 1971-1975.” The story focuses on the eponymous superhero battling aliens from the planet Polluto. Inhabitants of the planet can only survive in a world that is heavily polluted, but the Pollutians are experiencing upheaval due to their planet beginning to regenerate. As a result, three of the planet’s top officers are sent to earth to find a place that they can pollute enough to suit their needs. The aliens decide to focus on the Maritime provinces because of them being “disgustingly clean” and land their spacecraft near Fredericton.

As this is happening, Captain Enviro is lecturing school children in Prince Edward Island. He is quickly alerted to the arrival of the spacecraft and uses the power of his “pollutant-free ecobelt” to travel rapidly to New Brunswick’s capital city, where he battles the aliens until they flee in their spacecraft to Halifax. The Pollutians set a trap for the hero and force him to ingest a “magic mind pollutant” elixir that leads Captain Enviro to join the aliens on a polluting spree. Eventually, he regains his senses after being hit in the head by an errant bottle and he defeats the villains by attacking them (with the help of school children) with pure clean air, water, and soil. The comic concludes with the Pollutians sending one last form of pollution to the Maritimes, a noise polluting spacecraft. Captain Enviro quickly puts a literal cork into the craft, ending the alien invasion.

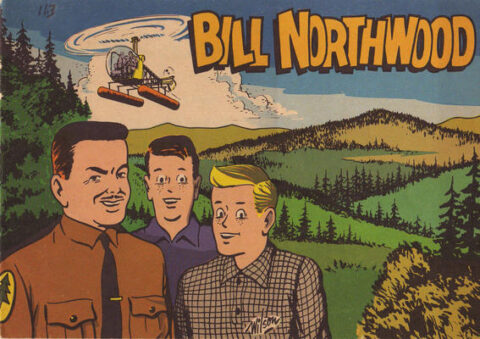

Additional government giveaways that were not created by Ganes Productions or Comic Book World were released throughout the 1960s and 1970s. The earliest environmental giveaway not published by one of the big two companies is likely Bill Northwood, which was published in 1968 through the federal Department of Forestry and Rural Development and distributed by the Canadian Forestry Service Department.

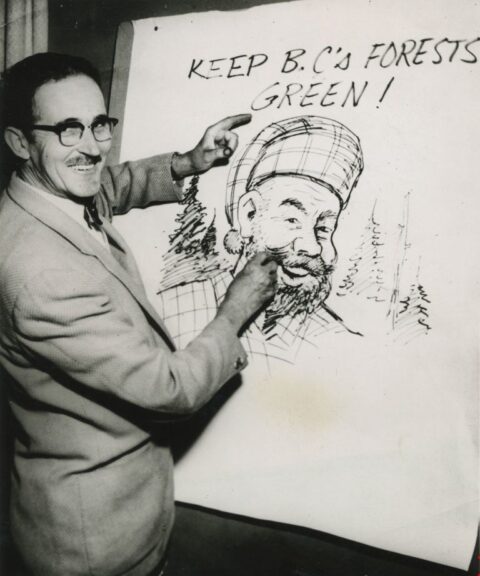

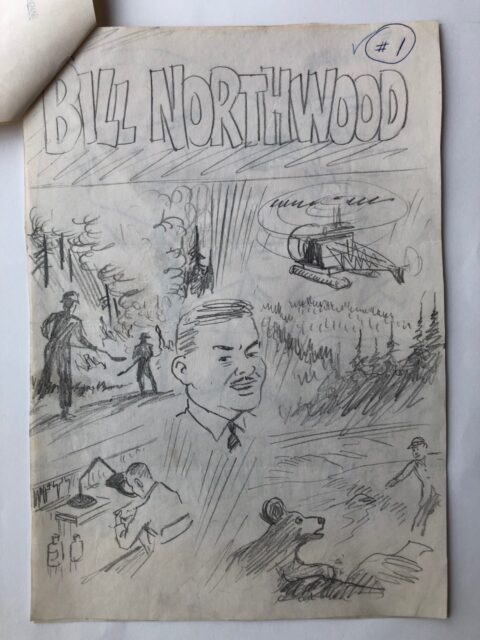

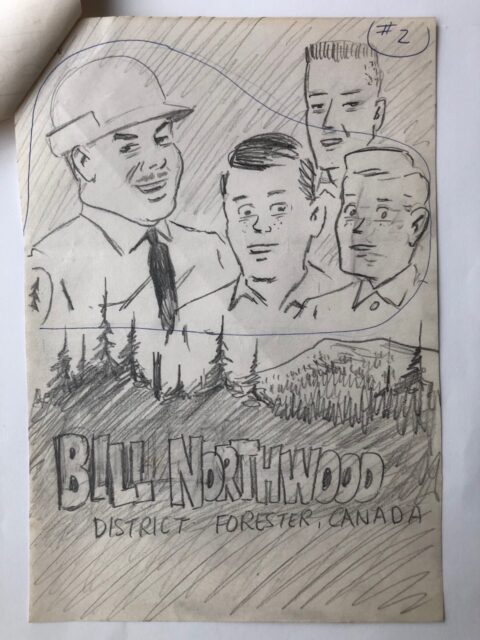

The comic was created by artist Fraser Wilson, who was born in Vancouver in 1905. Wilson was one of Vancouver’s legendary newspaper cartoonists, notably working for the Vancouver Sun from 1937-1947 before being fired for his labour activism during a newspaper strike. At the time, he was the chairman of the Co-ordinating Committee of Newspaper Unions. Wilson moved to Burnaby in 1943 and created the Bill Northwood character around the same time as part of a serialized cartoon of the same name. According to Jason Vanderhill, the comic strip was likely published in one of Burnaby’s newspapers at the time (the Burnaby Courier or Burnaby Examiner). The character is a resource manager and was created with the intention to educate the public about the importance of forests and why they should be preserved. It is likely that the comic book reprints Wilson’s earlier comic strips.

I have been aware of Bill Northwood for several years, but had not been able to learn much about the comic (or even the artist, outside of the name “Wilson” that is written on the cover of the comic) until, serendipitously, researcher and blogger, Jason Vanderhill, reached out to me as I was finalizing this month’s column. Mr. Vanderhill’s blog, Illustrated Vancouver, presents a wide range of illustrated material from the past and present that helps to tell the story of British Columbia. He covers comics from time to time and it is worth checking out.

After losing his job at the Vancouver Sun in 1947, Wilson was commissioned by the president of the Marine Workers’ and Boilermakers Union, Bill White, to decorate their hall. The resulting mural was over thirty metres long, depicted the BC labour movement and launched Wilson’s career as a muralist. When the building was sold in the 1980s, the mural was moved to is new home at the Maritime Labour Centre, but was shortened to twenty-six metres and was restored by Wilson and art conservator Ferdinand Petrov. Some of Wilson’s other murals are also still on display in British Columbia. Wilson died in 1992.

Earlier this year, a woman from California associated with Fraser Wilson reached out to Jason Vanderhill and sent him Mr. Wilson’s unpublished, hand-written (on loose leaf) autobiography, which he has generously shared online. The manuscript is hundreds of pages long and a relative of Wilson has recently completed a typed, revised version of the manuscript. Mr. Vanderhill also has access to an exciting cache of information and original material from Wilson that is not yet ready for the public, but that he envisions being made available to researchers soon. For now, I am very excited to be able to share the two cover prelims pictured above with his permission.

Other environmental giveaways that I have little information about include comics such as Energy and the Environment, which was published sometime in the 1960s in conjunction with the Ontario Ministry of Energy and 1973’s Let’s Unpollute. Both of these may have been created by Ganes, but additional information is needed to verify this.

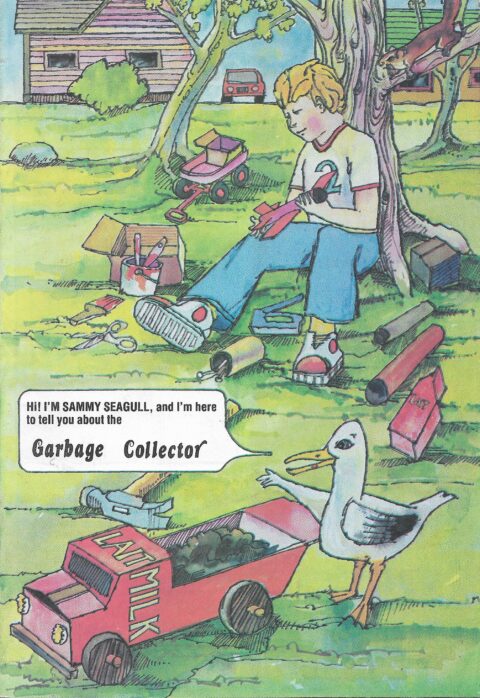

There is a later giveaway that I can verify is a sequel to World of Sammy Seagull, but was not created by McCarron and Edmiston. Garbage Collector was published in Sackville, New Brunswick in 1977 by Tribune Press Ltd., and was drawn by P. Walker (who I have been unable to identify). This sequel was designed and produced by Wildlands Associates and was released in conjunction with the Committee of Atlantic Environment Ministers. Rarely seen today, the comic is one of the only (and is perhaps the earliest) comic books published in the province of New Brunswick during the Canadian Silver Age.

By the end of the 1970s, Canadian giveaway comics were becoming a thing of the past (though they would make a huge comeback in the 1990s thanks to Jim Craig). Although giveaways continued to be produced for the duration of the Canadian Silver Age, they were few and far between. As the messaging around environmentalism changed and became more influenced by the counterculture movements of the 1970s, educational environmental giveaways came to an end in Canada to the extent that Garbage Collector is likely the last comic of this kind released in Canada during the era.

One of the things that stands out about how environmentalism was presented in these educational comics was that there was a major shift in how the topic was treated in the early to mid-1960s as being about conservation, land management and protecting industries to the late-1960s and throughout the 1970s as being preoccupied with pollution and littering. Next month, I will continue to look at environmental comics through the lens of the Underground movement that took centre stage in Canadian comics in the early-1970s and continued throughout the decade. Stayed tuned.

Hi Brian. My memories of the seventies, is that the Great lakes were pooched by chemical pollution from factories and mining. . I recall a school trip on a ferry in Toronto, and all I saw was oil slicks, dead fish and compromised water fowl.

In the early eighties I worked in a factory, and all the water waste was dumped into Georgian bay, chemicals and all. The plant was built in the 1960`s, and the drainage was run right out into the lake.

I think the awareness that comics and such brought, really helped drive the decision to clean the Great lakes up. They look so much better today.

Thanks for this comic history lesson Brian.

Wow… these giveaways are enough to make the Toxic Avenger weak in the knees! Great stuff Brian… I wonder what equivilant books were produced here stateside?

Thanks for your comment, Dave. I think that every province and territory is currently paying (in one way or another) for the lack of care paid to the environment for the sake of industry in one way or another. There are many toxic sites across the country and our oceans, rives, lakes, bays (and so on) are still feeling the brunt of pollution. I don’t have to look beyond Nova Scotia for examples that are still in the news like Boat Harbour. Next month, when I look at the environmental Underground comix from the 1970s, it will be clear that Canadians were not oblivious to all of this.

Gerald, I am not well-versed enough in American giveaways to provide you with any concrete answers. Given the volume of American giveaways produced in the 1960s and 1970s through companies such as Malcolm Ater’s Commercial Comics Company and the emergence of Smokey Bear, I imagine that there is a breadth of these types of comics waiting to be uncovered stateside. Some of Ater’s comics had Canadian editions, so I have taken a look at the list of comics he produced and there are a few environmental ones. Here is a link with a good overview of the Commercial Comics Company’s history and known comics: http://www.tomchristopher.com/comics2/malcolm-ater-and-the-commercial-comics-company/

3.5

Thanks for the link… that was very interesting!