As a socio-cultural anthropologist, the issue of representation has been part of my academic trajectory since I was an undergraduate. How issues such as gender and race are depicted in popular culture (and by whom) are topics that have been near and dear to me for a very long time. Few people know that my undergraduate thesis focused on the depiction of African Americans in 1960s Barbie dolls. I followed this with a Master’s thesis that looked at how “Cowboys” and “Indians” are an oversimplified North American myth that became prominently displayed in popular culture over time, starting with travelling Wild West shows and culminating in the characters of radio, film and television by the mid-20th century. Since earning a Ph.D. in socio-cultural anthropology requires ethnographic fieldwork, I switched focus away from issues of representation when I was working on my doctoral degree. That said, I still find it fun (albeit sometimes disheartening) to take a glimpse at issues of representation through depictions of race and gender in popular culture.

The topics that were the focus of my previous degrees offer some parallels with Canadian society, but the issues I tackled were very Americentric. When thinking about representations of race in Canada, our country’s particular history necessitates looking at the relationships between (mostly white) settlers and Aboriginal peoples (First Nations, Métis and Inuit). Indigenous peoples worldwide are often depicted as incapable of helping themselves and in need of saviours (or as villains or savages) in popular culture narratives and comic books have a particularly long history of these sorts of depictions.

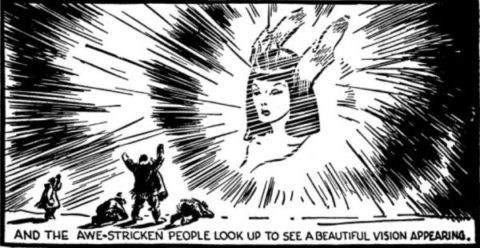

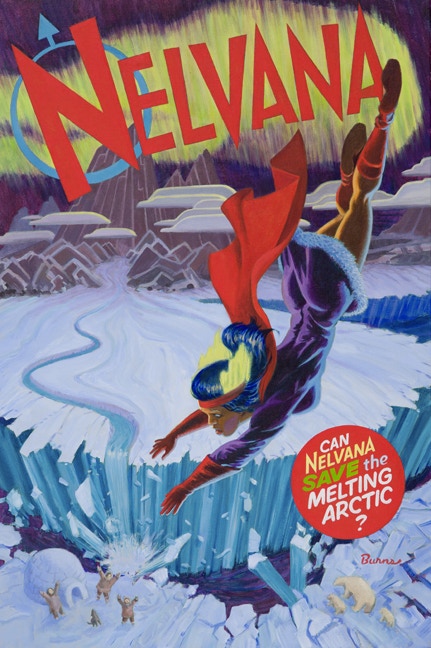

Something that I find particularly interesting about this, however, is that one of our earliest and best-known superheroes, Nelvana of the Northern Lights, breaks the mold, despite being problematic in some ways. Nelvana is a demi-goddess and superheroine. She is a “good guy” and Adrian Dingle tends to present her and the Inuit that she interacts with in his comic strips in a positive light. This is certainly a rarity for a 1940s depiction of an indigenous person in a comic book. Dingle’s Nelvana comics are one of the great specimens of the Canadian Golden Age, both narratively and artistically. What is problematic about Nelvana is that she is presented as looking like a white person, rather than Inuk, which makes little sense for such a demi-goddess and tells us more about how, even when depicted positively, expected tropes about indigenous peoples vs. white saviours may dictate such depictions. More recent renditions of the character tend to depict her as looking like an Inuk person.

During the Golden Age of Canadian comics, the Canadian arctic was little more than a fantasy. To this day, most Canadians live far to the south of the Canadian territories and few of us (including myself) have ever been to the “land of the midnight sun.” The far north of this country is as alien to me as a foreign country that I have only seen pictures of. Nevertheless, the north is part of the fabric of Canadian identity. The significant difference between the Golden Age and Silver Age of Canadian comics for the territories is that, for the first time ever, comics were being produced in the Yukon and the Northwest Territories (including present-day Nunavut, which is where the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation is located; I will return to this shortly).

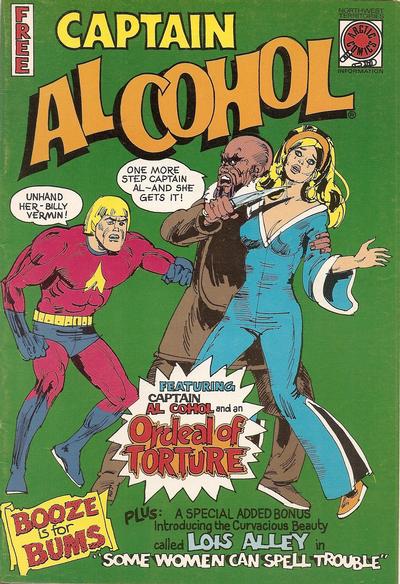

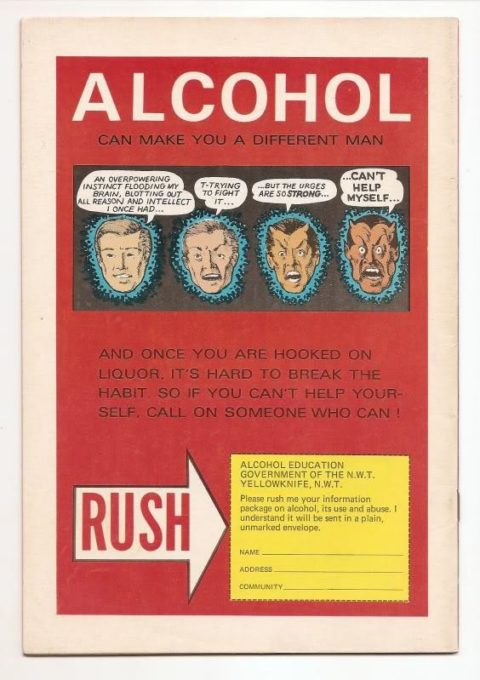

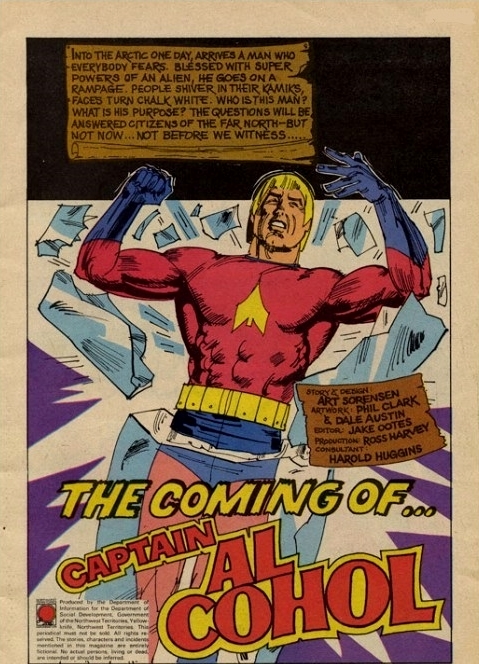

Admittedly, the output of comics in the Canadian north during the Silver Age was sparse. The first comics created in the north were the four issues of Captain Al Cohol that were released in 1973. All four issues were produced as giveaways by the government of the Northwest Territories (specifically, the “The Northwest Territories Department of Information for Northwest Territories Department of Social Development”) and were published under the name “Arctic Comics.” The series was created by Art Sorensen (a former northern correspondent to the Journal, who became a government information officer) with art by Phil Clark and Dale Austin. The four volumes focus on a white, blonde superhero named Allen Cohol, an intergalactic traveller who crashes into a pingo (an ice-covered earthen mound) only to be rescued by a group of Inuit hunters. Cohol has a weakness for alcohol, and the series follows his battles with various villains, such as Billy Vermin, while preaching about the dangers of alcohol. Throughout the series, the title character has numerous interactions with Inuit characters who have debilitating alcohol addiction problems. Captain Al Cohol has a severe alcohol problem himself and engages in disorderly conduct in the series such as crashing a snowmobile into a poll and participating in a barroom brawl while intoxicated. Ultimately, the title character succumbs to his weakness for alcohol, becoming homeless and ending up in jail. The series ends with Allen Cohol attending an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting.

According to the Encyclopedia of Canadian Animation, Cartooning and Illustration, the idea of these comics came from a priest who noticed that comic books were popular in the Northwest Territories and passed this information on to the chief of the government’s alcohol education program, Harold Huggins (who is credited as a consultant in the comics). The result was a bizarre superhero giveaway comic that received plaudits in southern parts of Canada and the United States, but a muted response among its target Inuit audience.

An article appearing in the September 18, 1973, issue of the New York Times by William Borders notes that the purpose behind these comics was to attack alcoholism, which had become one of the main social problems in the Northwest Territories. The author rightly insists that sociologists, “trace it to the disruption of the Eskimo and Indian societies and the destruction of their values that has been part of the white man’s rush north for oil and other minerals.” This was not a popular sentiment in the 1970s but is now a much more mainstream approach to understanding some of the social determinants of health amongst Aboriginal populations in Canada.

The New York Times article mentions that 8,000 copies of the four issues were produced, but I suspect that the majority of these were sent to libraries throughout Canada and the United States. Due to low literacy rates in the north at the time and the production of a white saviour trope (albeit a flawed white saviour), it is not surprising that the target audience was not as receptive to this comic as readers elsewhere in the continent. Indeed, the April 1975 issue of Inuit Today includes a cartoon rendition of the gravesite of Captain Al Cohol drawn by artist and staff writer, Alootook Ipellie, in accompaniment with an article celebrating the demise of the series. Perhaps the greatest Inuk political cartoonist of all time, Ipellie was posthumously inducted into the Canadian Cartoonists Hall of Fame in June this year.

The reality is that government policies around alcohol in the Canadian territories were based on a series of, as anthropologist Pamela Stern says, “simplistic, decontextualized, paternalistic, and racist administrative discourses about the cultural and psychological characteristics of Inuit and their drinking habits.” Stern takes the comics to task for being a distinctive example of the attitudes towards Inuit drinking during the 1970s but provides a great overview of how government attitudes and policies around alcohol have changed emphasis over time (beginning in the 1950s). Her article, “Super Shamou versus Captain Al Cohol: Inuit Cultural Productions and Discourses on Inuit Drinkers” was published in 2015 in Topia: The Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies. A PDF of the article is available online and you can see it here.

Today issues of Captain Al Cohol are nearly impossible to procure. Few collectors who I have discussed this series with own copies and those who do are not interested in selling. Dan, Victor and I have spent a couple of years trying to track down copies with no luck and we have not seen a single copy come up for sale during this time. That said, readers of Comic Book Daily who live in Niagara Falls, Ontario can see one of the issues on display at the Canadian Comics Corner at Big B Comics.

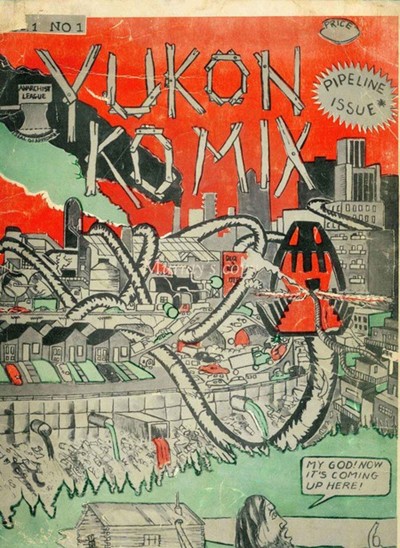

Captain Al Cohol was followed in 1978 by John Lodder’s rarely seen two issue series Yukon Komix. Lodder’s series is best thought of as an example of the Underground Comix genre and the two issues had low print runs of 500 copies each. Since Lodder’s comics were mostly circulated around Whitehorse, it is impressive that John Bell was able to identify them and included them in his 1986 guide Canuck Comics. Supposedly few copies remain in private collections, particularly of issue # 2, as Lodder destroyed his unsold copies after becoming a born-again Christian. I have only ever seen a couple of the interior pages of the first issue, which features a story about a fox being chased by a hunter after destroying his trap lines. This leads me to believe that this series has a northern flair to it, but without additional information, I cannot be entirely sure.

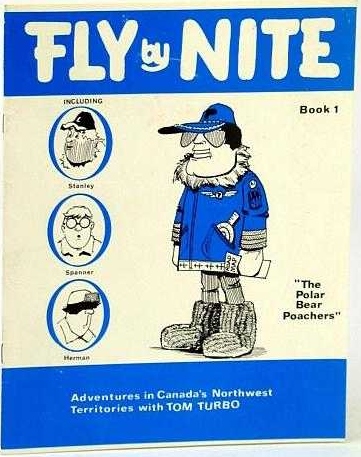

As far as we can tell, the two issues of Yukon Komix were the only comics published in the Yukon territory during this era. The remaining comics that came out of the Canadian north mostly came out of the Northwest Territories. The next series that we have identified is the three-issue series Fly by Nite by Wally Wolfe. We only have been able to uncover skeleton data about this series. We know that it was published in 1981 and were able to find cover scans for the first two issues through Abebooks.com, but are unsure what the contents are like or how many copies of each issue were produced. All that we have been able to learn is that the series focuses on an arctic adventurer named “Tom Turbo.” Wolfe also published a one-shot in 1985 called North of 60: The Funny Side. Unfortunately, like his earlier comics, we know virtually nothing about this comic. Wolfe continued to do illustrations for various books in the Northwest Territories into the 1990s, including Elisa Hart’s Getting Started in Oral Traditions Research and also provided illustrations for some aviation themed children’s books by Shirlee Smith Matheson.

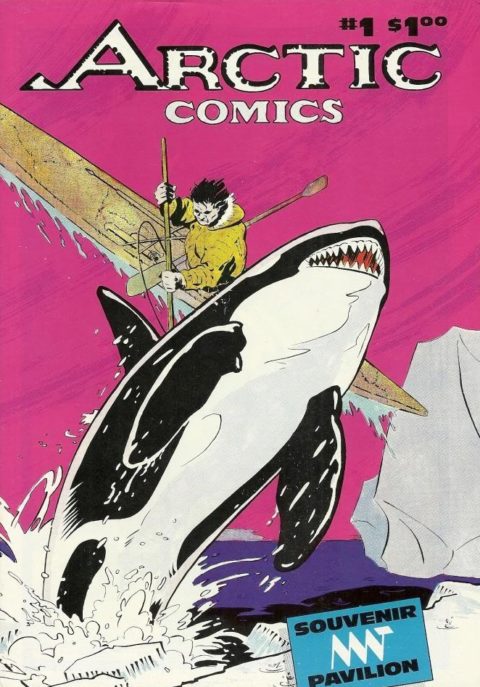

Perhaps my favourite comics produced in the territories during the Silver Age are those drawn by (and sometimes written by) Nicholas Burns and published in Rankin Inlet, Northwest Territories (now Nunavut). Burns produced four different comics during the era, beginning with 1986’s Arctic Comics # 1, which was a souvenir comic originally sold at the 1986 world exposition in Vancouver. The issue was later rebranded as True North # 1 (not to be confused with the series of the same name produced in 1988 by the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund), with a second issue appearing in 1989. What sets Burns’ work apart from the other comics produced in the territories in the 1970s and 1980s is that his artwork is extremely professional (he had worked as an assistant for George Freeman and then became a colourist for Marvel in the early 1980s) and his protagonists are strong Inuit characters, while also avoiding the white saviour trope.

Burns spent nearly a decade living in the Northwest Territories (beginning in 1984), which seems to be a strange place for a comic book artist to relocate to during the pre-internet days of the 1980s. In reality, he moved to the north to accompany his late wife, Dr. Lisa Lugtig, who he told Jason Wilkins in an interview for Broken Frontier in 2016 had wanted to live in the arctic since grade school. After their ten-year adventure in the north, the couple returned to Winnipeg, where Burns has worked as a freelancer ever since and where Dr. Lugtig continued to practice medicine until her death in 2003.

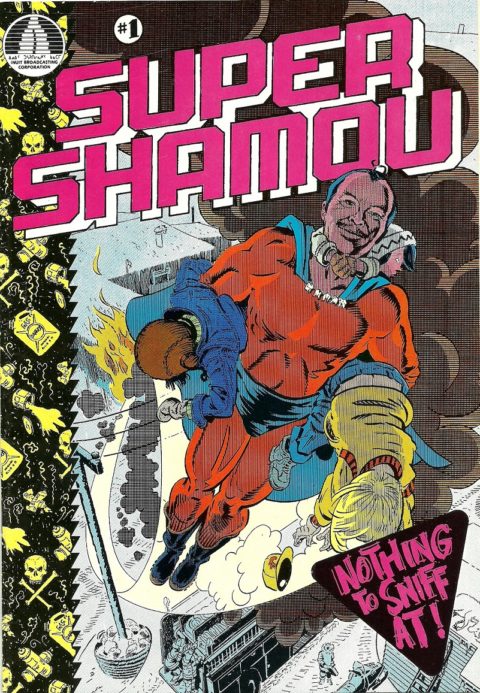

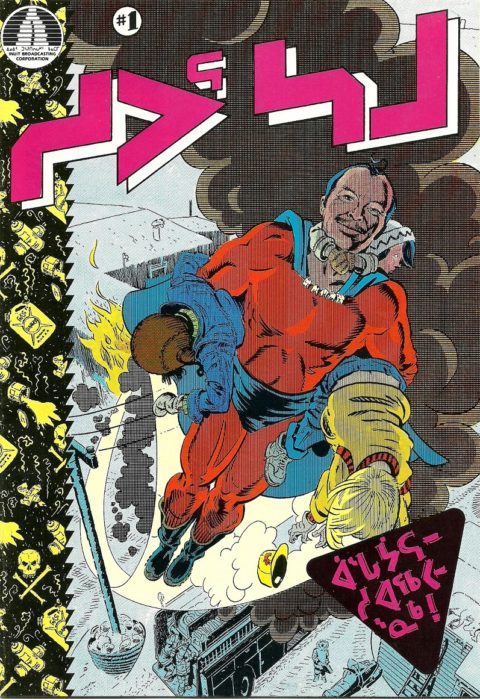

In addition to the issues of Arctic Comics and True North mentioned above, Burns also published the lesser known New North: Stay in School with Michael Kusugak in 1990 and, in my opinion, the most important comic to ever come out of the territories, Super Shamou (also published in 1990). Both of these comics were published in English and Inuktitut, with Super Shamou also having a French and Inuktitut edition. Half of the comic is in English or French and ends at the centre wrap. Flip over the comic and it is reprinted entirely in Inuktitut. The Inuktitut translation is by Micah Lightstone. As such, these were the first comics ever published in Inuktitut.

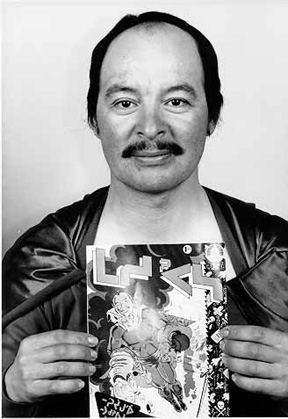

What makes Super Shamou particularly special (indeed, it is probably my favourite Canadian giveaway comic ever made), is that in addition to offering a translation in Inuktitut, the comic features an Inuk superhero, created by two Inuit men, as its protagonist. Created by Barney Pattunguyak and Peter Tapatai in 1987, Super Shamou teaches Inuit children about the dangers of sniffing solvents to get high. As the story goes, a mild-mannered Inuk man named Peter awakens one night in his bed to find himself face to face with a spirit who informs him that he has been chosen to become a protector of the arctic. He is provided with a necklace that grants him superpowers (including flight, superhuman strength and resistance to cold).

Super Shamou was published in conjunction with the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation (IBC). Incorporated in 1981, IBC was the first Native language television network in North America insofar as it produced content in Inuktitut (with some programming in English). In 1986, IBC launched its most famous program, Takuginai, which taught children Inuit language, traditions and values through the use of puppets.

What makes Super Shamou additionally important amongst northern audiences is that the property was not merely a comic book. Rather, Pattunguyak and Tapatai’s creation was financed by IBC as a series of short films for children. Not only did Tapatai play Super Shamou in the television shorts, but Burns also used his likeness for the comic book. IBC has links for two of the shorts on its website, which you can see here and here. Note that both shorts are in Inuktitut.

Depictions of Indigenous people in popular culture are often been problematic. The issues of who creates these representations, the purpose(s) behind such depictions and who the target audience is are all worthy of discussion. The creation of Captain Al Cohol as a government tool directed towards educating Inuit about the dangers of alcohol is a material example of how such depictions can be problematic. Super Shamou is the antithesis of Captain Al Cohol. As a character created by two Inuit men as an educational tool directed towards Inuit children that were made available in the Inuktitut language, Tapatai and Pattunguyak’s character achieves a level of credibility that few Inuk characters that came before it ever could. The artwork of Nicholas Burns brought this character to life in comic form and the legacy of the character, television shorts and comic book live on to this day. An entire generation of Aboriginal artists and writers that are active today have the ability to look back at Super Shamou as an example of how a character can be created with success without the intervention of outsiders projecting myths stereotypes and tropes or misguided government policies onto them.

Today there is a growing and healthy number of Aboriginal comic creators working in Canada. If you are interested in learning more about this topic, I recommend checking out both volumes of Moonshot from Bedside Press and 2016’s Arctic Comics which features work by Michael Kusugak, Germaine Arnaktauyok, Jose Kusugak, Susan Shirley and, of course, Nicholas Burns.

As a final note, the issue of racial representation is part of a larger shift in Canadian comics today. Additionally, we have more superstar female creators and publishers coming out of this country than ever before. Women such as Fiona Staples, Kate Beaton, Kate Leth, Hope Nicholson, Jillian Tamaki, Julie Rocheleau and Faith Erin Hicks (just to name a few) have all had their works nominated for major awards over the past few years. This is a good thing and it’s getting better.

Just last night we were excited to learn that our good friend Jay Aaron Roy and his shop Cape and Cowl Comics and Collectibles in Lower Sackville, Nova Scotia, was nominated for the prestigious Harry Kremer Award. Jay may operate the only Trans-owned comic shop in Canada and offers a safe space for LGBTQ+ youth in addition to various community outreach programs. Representation matters and comics are for everyone.

I never tire of enjoying well-researched articles such as yours, brian. Bravo!

Thanks, Tony. Much obliged!