Welcome back to the final part of my three-month-long look into the major Canadian publishers from the 1980s. Since December, I have covered (in broad strokes) the important contributions to the history of Canadian comics made by the largest Canadian comic book companies from that decade: Aardvark-Vanaheim, Vortex and Aircel.

Beyond these “big three,” there are two additional companies that deserve a closer look as part of this broad history. These two companies did not publish nearly as much material as the big three, but Matrix Graphic Series and Strawberry Jam played important roles in establishing Canadian comics during the decade and they have cemented their legacies today for wildly different reasons.

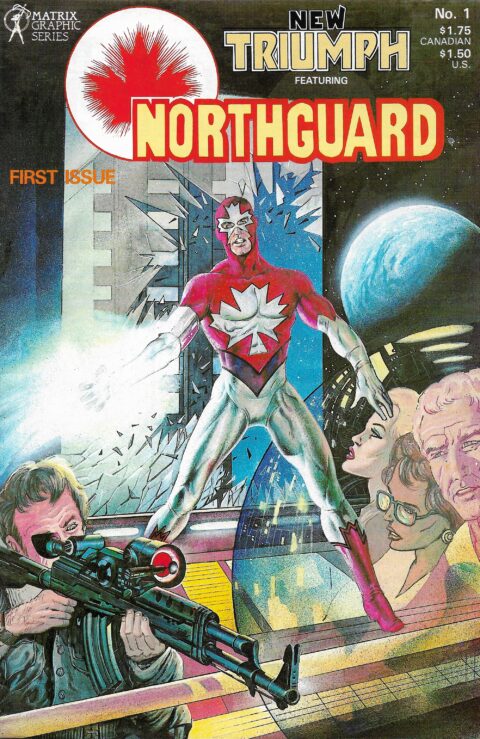

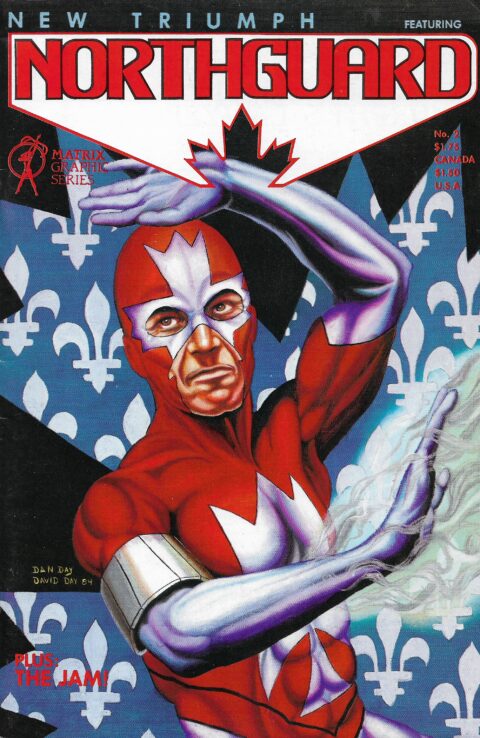

Matrix Graphics Series was based out of Montreal, Quebec, and was spearheaded by editor-in-chief Mark Shainblum and art director Gabrielle Morrissette. The company’s first series, New Triumph (featuring Northguard) debuted in September 1984. The first issue of the series featured a cover by artist Peter Hsu and debuted the era’s final major nationalistic superhero, Northguard (the comic’s title character). The second issue of New Triumph debuted another important Canadian character: Bernie Mireault’s “The Jammer” starring in the backup story, “The Jam.” The series lasted for five issues and was quickly followed by two additional series: MacKenzie Queen in 1985 and Dragon’s Star in 1987.

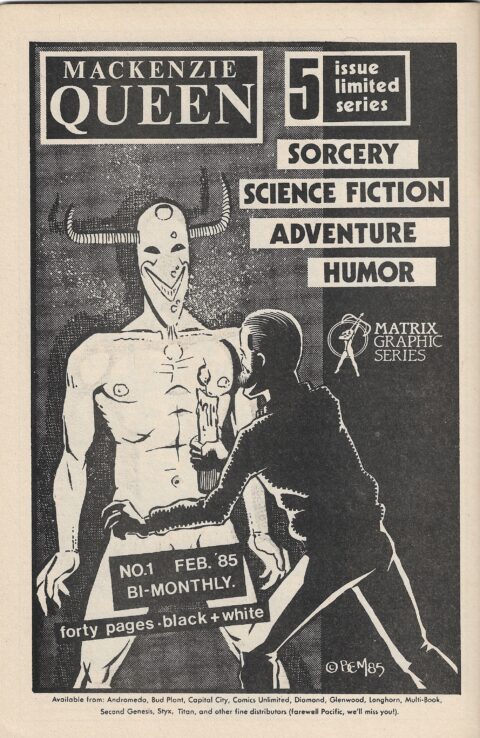

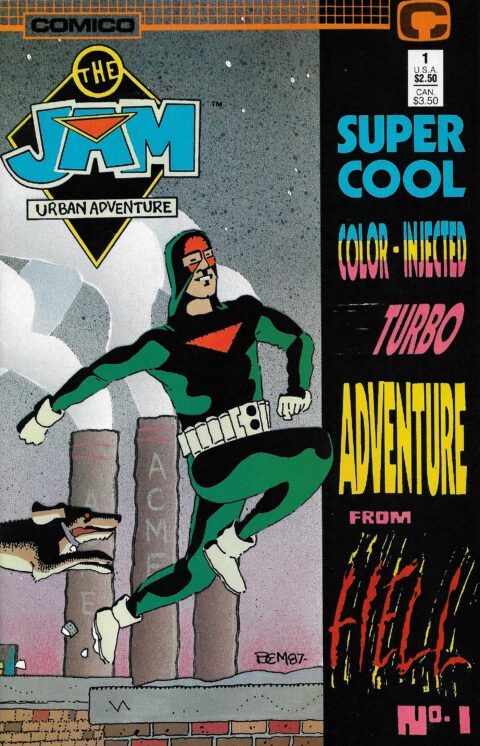

Like New Triumph, MacKenzie Queen lasted for five issues. The series was written and drawn by Bernie Mireault and is a bonkers sci-fi/fantasy story that helped Mireault emerge as one of Canada’s up and coming comic book creators. MacKenzie Queen, as well as Mireault’s The Jam stories in New Triumph, are some of my favourite stories from the major Canadian publishing companies from the 1980s. The Jam was popular enough to feature in his own one-shot in 1987, the appropriately titled The Jam Special. This was followed in 1988 by a second one-shot, The Jam: Super Cool Color-Injected Turbo Adventure from Hell # 1, which was published by the American company Comico as part of an agreement with Matrix.

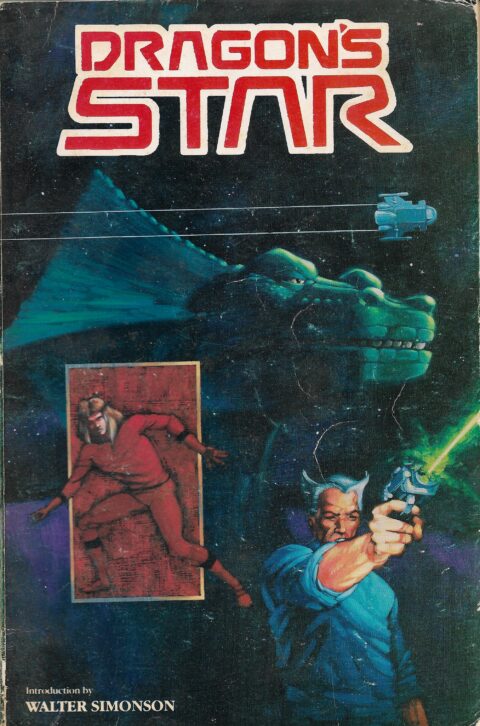

Dragon’s Star was a dystopian sci-fi series set in the distant future. The series was written by New Brunswick novelist and family doctor Mary Ann Bramstrup and drawn by artist Ian Carr (who had already worked on several comics for Potlatch Publications earlier in the decade). Bramstrup met Shainblum through Deni Loubert at Maplecon and the project came together as soon as Carr came on board. The series lasted for three issues before Matrix Graphic Series ceased publishing at the end of 1987 due to the market collapse. The series went unfinished until Michigan’s Caliber Press picked it up in 1989, releasing the first three issues, plus the unfinished material in graphic novel form with an introduction by Walter Simonson. Caliber would release a second series in 1994 called Dragon’s Star 2, again written by Bramstrup and with contributions from Simonson. Carr was replaced by artist David Cullen and inker Peter MacDougall. Unfortunately, the second series was cancelled after two issues and as far as I know, was never completed.

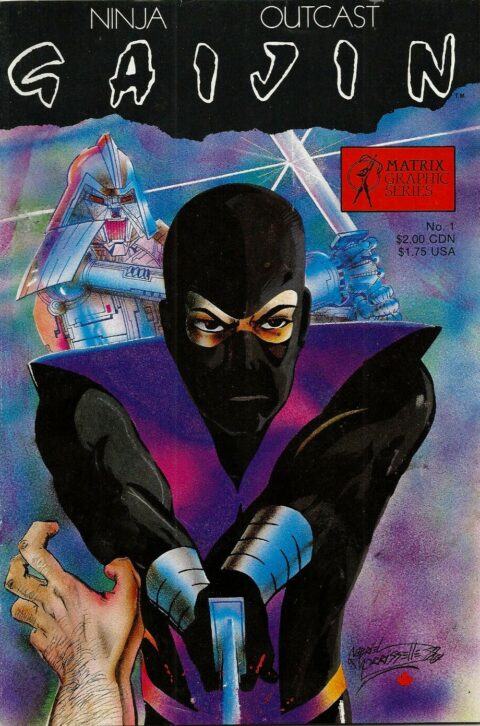

Matrix Graphic Series released two additional comics in 1987 before it ceased operations: Monique Renée’s Cybercom, Heart of the Blue Mesa and the little-known Ninja Outcast Gaijin. I assume that both comics were intended as ongoing series, but I cannot be sure at this time. Either way, each comic lasted for only one issue.

At the same time that Caliber Press published the finished Dragon’s Star graphic novel, the company released collected MacKenzie Queen and Northguard graphic novels too. Caliber also breathed new life into Northguard by publishing the three-issue miniseries Northguard: The ManDes Conclusion around the same time. Northguard would reappear as part of Chapterhouse’s “Chapterverse” in 2016 and continues to appear in comics published by the company today.

1989 also saw Mireault continue working with his Jammer character, this time in his own standalone series The Jam: Urban Adventure. The first five issues of the series were published irregularly by Slave Labor until 1991. In 1992, Tundra reprinted all five issues of the Slave Labor series. New issues started returned with issue # 6 in 1993, this time with Dark Horse, which would continue publishing the series through issue # 8. The series then moved again to Caliber in 1995, where it would end with issue # 14. Yet, this was not the last we would see of The Jam, as the character would team up with Mike Allred’s Madman in 1998 in the two-issue series Madman/The Jam at Dark Horse. The character has made sporadic appearances ever since. Needless to say, The Jam’s confusing publication history is worthy of a column in and of itself.

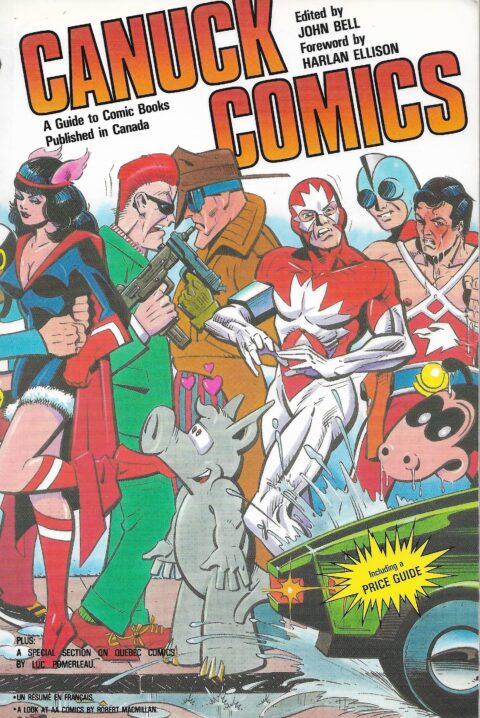

Despite Matrix Graphics Series releasing fewer than twenty individual issues during its run, two of its series and several of its characters remain hallmarks of the era. The company also helped to champion the emerging interest in Canadian Golden Age comics and the wider Canadian comic book scene in ways that continue to help collectors and researchers today by releasing John Bell’s guide Canuck Comics in 1985. Today, the three biggest names associated with Matrix Graphic Series have all been elected to the Canadian Comic Book Hall of Fame: Shainblum in 2016, Morrissette in 2017 and Mireault in 2020.

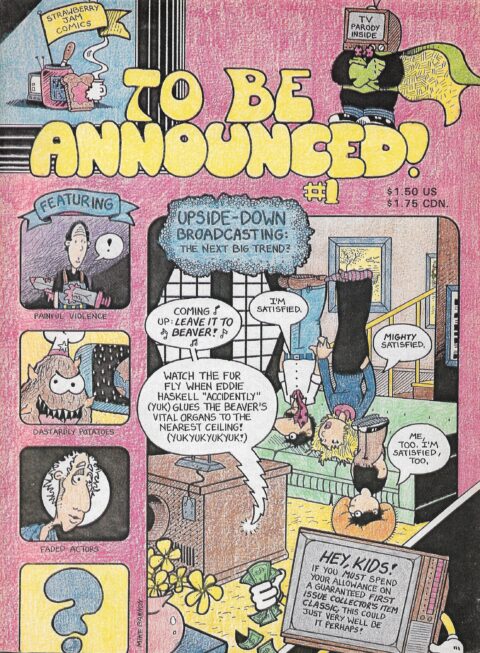

The final company on my list of key Canadian publishers from the 1980s, Strawberry Jam, is likely the least known among the group. The company only released sixteen comics during a seven-year period from 1985-1992. Founded in Edmonton, Alberta by Derek McCulloch and Paul Stockton, the company’s only significant output consists of two seven-issue series. The first was the humorous anthology series, To Be Announced, which ran from 1985-1987 and featured artwork from Mike Bannon and the mononymous “Alexander.” McCulloch and Rick Wilson tended to write the scripts for the stories included in the series, with occasional contributions from several other writers, including Liz Schiller.

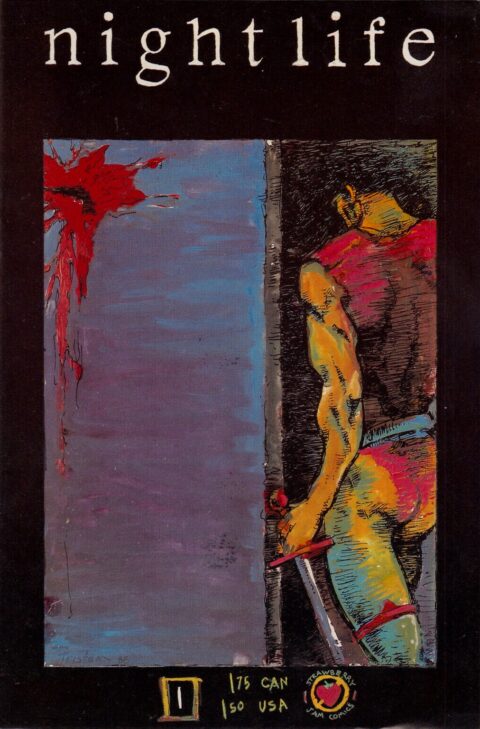

Strawberry Jam’s second series, night life, was a dark, horror-themed title that would have fit well as a Vertigo title. The series ran from 1986-1988 and was written by McCulloch and drawn by Simon Tristam, with editing by Schiller and McCulloch. Both of the series also featured a “Presidential Address” from Stockton at the beginning of each comic. An eighth and final issue of the series was released by Caliber Press in 1991. The only other comic released by Strawberry Jam in the 1980s was the seventh and final issue of Jim Bricker’s Open Season, which was previously published by Renegade Press until the company folded in 1988. Strawberry Jam effectively stopped printing comics after this, with one exception: 1992’s one-shot OOMBAH Jungle Moon Man # 1.

Although To Be Announced and night life are great series and Strawberry Jam was the only major company operating out of Alberta at the time, they were a bit late to the party when it came to taking advantage of the growth in black and white comics. Despite this, the reason why the company and its major figures (especially Stockton, McCulloch and Schiller) are such an important part of the fabric of Canadian comics is because of what came next.

In September 1987, the RCMP raided the comic shop Comic Legends in Calgary Alberta, seized nearly two hundred comics, and charged owners Julie Warren, Darren Ott and Dale Clarke with circulating obscene materials. The lore around the incident involves an upset mother complaining to police that her fourteen-year-old son had purchased an issue of Aircel’s Warlock 5 at the store. Yet, the Aircel publication was not what was seized. Instead, the comics in question were adult comics and this incident is part of the long history of comics being illegal in Canada after the establishment of the Fulton Bill decades earlier. The shop and its proprietors were found guilty of possessing and selling obscene materials in November 1988 and were issued fines. This incident is one of many examples of its kind in Canadian history, but this time the industry took a stand. The law had been selectively enforced for its entire lifespan, but incidents had ramped up since the early 1970s and I have spoken with several store owners from the Canadian Silver Age who had the spectre of the RCMP looming over them at this time.

Making sense of the Fulton Bill and its effect on the comic industry in Canada may seem tangential and its history is worthy of a book-length treatment. For this reason, I will only delve into some of the more significant aspects of this history here.

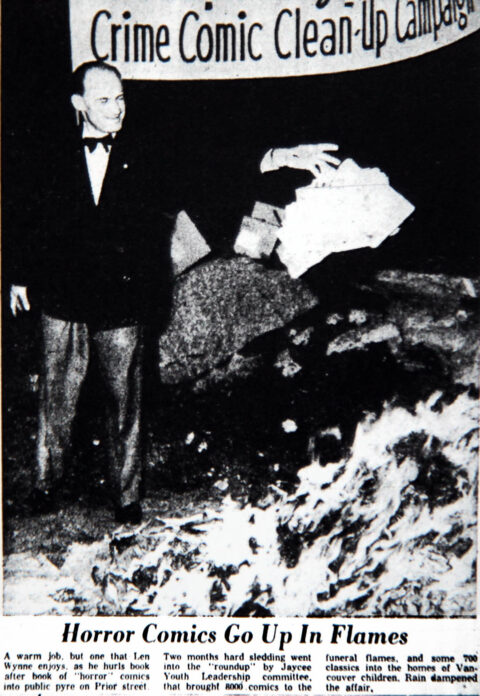

Towards the end of the 1940s, there was a growing moral panic around crime comics in Canada and the USA. In the USA, this was spearheaded by Dr. Fredric Wertham whose questionable academic work connecting juvenile delinquency to crime comics was gaining traction at the time. Wertham’s work eventually culminated in the publication of his 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent. That same year, Wertham and Fulton testified before the American Senate Subcommittee on Comic Books and Juvenile Delinquency. The subcommittee targeted William Gaines and his E.C. Comics specifically and, as a result, the comic industry in the USA adopted the Comics Code Authority, a self-regulating ratings code that appeared on almost all mainstream comics in the country until 2011.

Comics were not outlawed in the United States, but by this time crime comics had already been illegal in Canada for approximately five years thanks to Fulton. Davie Fulton was an MP based out of Kelowna, BC from 1945-1968. By the late-1940s, the moral panic around crime comics was already taking hold in Canada due to the work of Wertham and hyperbolic news articles making connections between criminality and comic book reading. Fulton was already making noise for trying to legislate banning comics in Canada in July 1948, but his efforts were rebuked. Then, in November that year, a high-profile case occurred in Dawson’s Creek, BC, where two young boys stole a rifle and ammunition from a vehicle and planned to rob the next car that drove past them on the Alaska Highway. They subsequently shot sixty-two-year-old James Watson. Watson died four days later. In the aftermath of this event, it was learned that the boys were voracious comic book readers. Comic books became a convenient scapegoat, fit Fulton’s narrative and the moral panic was in full swing.

By February 1949, Fulton had submitted legislation in the House of Commons making crime comics illegal in Canada. Bill C-10 (which came to be known colloquially as the “Fulton Bill”) became law on December 5, 1949. In the immediate aftermath of this, the Canadian government targeted newsstands, stores selling magazines and the last Golden Age Canadian comic book publisher, Superior. This hastened the complete collapse of the comic industry in Canada by the mid-1950s, which was already under pressure.

In the decades that followed, the laws were selectively enforced. Technically, almost all comics sold in Canada from 1949 until 2018 (when the law was repealed) could be considered crime comics. Manitoba was particularly aggressive with enforcing the Fulton Bill, with the Winnipeg Police Morality Squad engaging in numerous stings during the 1950s. The laws became aggressively enforced again during the 1970s when small comic shops (like Frank McTruck’s New Universe Comics in Winnipeg) began selling underground and alternative comics in Canada, some of which were made in Canada, but the majority of which were coming out of California. People like McTruck found themselves embroiled in a cat and mouse game with police and border security and tended to go out of business due to large fines and possible criminal charges in the days before comic shops were commonplace in Canada.

By the 1980s, with Canadian comics again being nationally published, the rapid growth of comics as collectibles and the emergence of local comic book shops catering to readers of all ages and stocking adult materials, police started targeting comics shops again. This time, however, industry insiders were ready to fight back. The Comic Legends raid was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Of note is that the same thing was happening in the USA. In 1986, Denis Kitchen started the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF) in response to the arrest of Michael Correa, manager of Friendly Frank’s comic shop in Lansing, Illinois, for distributing obscene material. In this case, the obscene material included comics published by Kitchen Sink. The die was cast on both sides of the border and this time the comic industry was taking a stand.

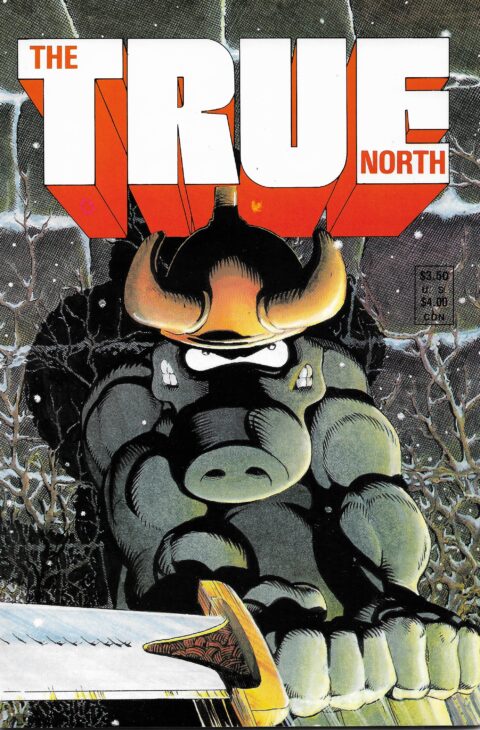

After the creator community caught wind of the Comic Legends incident, Stockton, McCulloch, Schiller and Leonard S. Wong started the Comic Legends Legal Defense Fund (CLLDF) in order to raise money to help the shop owners fight the charges and pay off their fine. In order to do so, the organization released the comic The True North, with proceeds going to the shop owners. The comic included a “hinterland who’s who” of Canadian creators from the era, including Chester Brown, David Boswell, R.G. Taylor, Dave Sim, Ron Kazman, Ronn Sutton, Ty Templeton, Dave Darrigo, Mark Shainblum, Gabrielle Morrissette, and even a young Todd McFarlane (among many others). American’s living in Canada also contributed to the comic, including George Metzger and Joe Matt. A second volume of the series, The True North II, was released in 1991 as a statement against censorship.

I cannot understate the importance of this movement. Canadian comic creators and the shops that sold their work were under attack because of a decades-old law that violated Section 2(b) of the recently established Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (which itself had been signed into law by Queen Elizabeth II on April 17, 1982).

The Canadian Charter Rights enabled companies and individuals to begin combating censorship in this country by targeting outdated obscenity laws. Other media, including the fledgling home media industry and literature and print media (especially gay and lesbian publications), faced similar problems to those of comic books. Inevitably, the BC independent bookstore, Little Sister’s Book and Art Emporium filed a claim against the government in 1990 challenging the Canadian Border Services Agency’s (CBSA) perpetual confiscation of their inventory at the border. It took ten years for the case to wind its way through the courts before the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in favour of Little Sister’s in 2000. The case established that the CBSA had to prove that the materials they confiscated were indeed legally obscene, preventing the agency from being arbitrarily allowed to confiscate material as they saw fit. The decision had ramifications for all importation of media in this country, including comic books.

After 1991, the CLLDF went mostly dormant for the next two decades. In 2011, the organization re-emerged to assist an American citizen whose laptop had been seized by officials at the Canadian border and who was subsequently charged with “child pornography” based on comic illustrations found within. The organization fought to raise public awareness about the unjust charges and contributed money to his legal expenses. Eventually, the charges were dropped, but the CLLDF registered as a non-profit at this time and has been much more active in the years since. In 2020, the CLLDF raised funds for Canadian comic stores that were shuttered as a result of the pandemic. Two of my close colleagues and friends in Atlantic Canada were helped directly by this initiative, as I wrote about last October. CLLDF President Leonard Wong and board member Jay Bardyla were among the recipients of the 2020 Joe Shuster Awards’ TM Maple Award for their efforts.

The beginning of the CLLDF was essentially the end of Strawberry Jam, but the contributions of the non-profit have had a far-reaching impact on the comic industry ever since. Indeed, raids on comic shops became increasingly uncommon after the CLLDF brought attention to the problem and soon ceased altogether. By 2017, the federal government considered the Fulton Bill to be a “zombie law” and news media across the country ridiculed its continued existence in the criminal code (alongside child pornography laws, of all things). The federal government repealed the law in 2018, meaning that the majority of comic books in Canada had been illegal to buy, sell or own for nearly seventy years.

My overview of these companies over the past few months barely scratches the surface of the incredible output of Canadian comics throughout the 1980s. The comics published by the five major companies I have profiled make up the bulk of the comics published during the Canadian Silver Age. There were many more comics published during this time and distinct DIY comic movements were established in British Columbia and Quebec during this era too. I hope to return to some of these topics later this year.

The good news for collectors is that the majority of comics published by Aardvark-Vanaheim, Vortex, Aircel, Matrix Graphic Series and Strawberry Jam tend to be inexpensive on the secondary market and can often be found neglected in the dark corners and forgotten long boxes of comic shops across Canada. As such, acquiring some of these comics should not cost you an arm or a leg and this is a great way to whet your appetite for Silver Age Canadian comics, especially if you are a fledgling or entry-level collector. This is a great starting point to explore the lasting legacies of the comics that were published at the end of the era.

Interesting article, brian. I knew nothing about the Canadian silver age until I started reading your great articles.

One question, though, even though the Fulton law was repealed in 2018, wouldn’t comics released from 1949 to 2018 still be illegal, as they would fall within the years set by the parameters of the law’.

Thanks for your comments, Klaus. I’m glad that your are taking an interest in the Canadian SA as a result of my column.

This is a good question. My understanding is that the distribution, sale or ownership of “crime comics” in Canada became legal as soon as the law was repealed, regardless of what year a particular comic was released. I suppose that it is possible that the RCMP could charge someone with an historical crime using the old law for something that happened in the past, but I cannot imagine a reason why they would want to.

In a time where people nowadays are being held to account for things their ancestors didn’t even do but are guilty of association because they lived during that historical period, if a mass murderer confessed that reading old crime comics led to his delinquency, would that cause the police to pursue the stores, publishers snd distributors of said materials from that time?

How’s that for a tough question?

Well Klaus, I am not involved with the criminal justice system, but I would like to think that in this day and age that the police and lawyers would be more interested in the actions of the murderer in your hypothetical example than whether or not said murderer was reading comics. That said, there is no such thing as a statute of limitations in Canada and moral panics tend to lead to scapegoating of one kind of art form or another, so it’s not outside of the realm of possibility.

I am just glad that after almost seventy years of “crime comics” being illegal in Canada that distributors, comic shops and collectors do not have to worry about police shakedowns in 2021. What happened to Comic Legends is just one of a myriad of examples of the enforcement of the law in the past and, in my opinion, the law should have never existed in the first place.

I’m glad you mentioned John Bell’s Canuck Comics. That, along with his follow-up volume Invaders From the North are invaluable reference works for anyone interested in Canadian comics. These were the works that really sparked my interest in Canada’s Golden Age and Bell’s collection is the linchpin of Library and Archives Canada’s Golden Age collection, another invaluable resource. Canuck Comics has a chapter by Bob MacMIllan who is the chap who wrote the online Canadian Encyclopedia of Animation, Cartooning and Illustration (canadianaci.ca). Bob’s collection has found a home at McMaster University and includes illustrated materials from 1867 to 2017, another invaluable resource. I should add that both books cover significant material from our Silver Age too, including my all-time favourite, Yummy Fur!

I’ve really enjoyed this romp through the bigger Canadian publishers of the ’80s. Most of these titles have crossed my path or ended up in my collection over the years. I don’t think most people are really familiar with the huge output of Canadiana in this period. Even in the ’70s, after the blush of Centennial had faded, there was a huge surge in the Canadian arts, including, film, television, theatre, music, art, literature and…comic books! I look forward now to hearing about some of the little guys too! Great post, my friend. Always a treat!

mel, “Canuck Comics” and “Invaders from the North” are the most important tomes ever written about the history of Canadian comics. They are a must-read for anyone interested in the subject. Canuck Comics is a great starting point, but since it was published before the Canadian Silver Age ended, it does not offer a complete list of comics from the era. Dan, Victor and I have also identified hundreds of comics that Mr. Bell was not aware of at the time. Nevertheless, Mr. Bell and his colleagues’ efforts during the pre-internet era were quite successful. MacMillan’s essay about Anglo-American comics found within the book is a good read and, of course, I encourage Forgotten Silver readers to check out his online encyclopedia.

Invaders from the North is an even better jumping off point for people interested in the subject, as Bell provides a broad overview of the history of Canadian comics from WECA to the early 2000s, while also offering a social history of sorts. Both of these books have a place on my shelf.

There is one additional book that I think is a must-read for people interested in the history of Canadian comics, with the caveat that it is written in French (and I am not aware of an English translation): Mira Falardeau’s 1994 book “La bande dessinée au Québec.”

I’m glad you enjoyed my columns about mainstream Canadian comics from the 1980s over the past three months. I will be covering more obscure material again soon.

Nice work, as always!

Good article. Takes me back.