For the past few months, I have focused on a handful of bizarre, low-quality “gutter” comics from the 1980s. This has been a fun exercise for me, but I think it is time to break things up with something completely different. I still have many other such comics to discuss and will return to that thread again later.

Something that I rather enjoy is using this column as an opportunity to present a cultural history of Canadian subjects that have appeared in comic book form. Sometimes this means looking at a better-known figure or character from yesteryear that appeared in a comic book as part of a larger cultural or creative trajectory. One such figure is Elmer the Safety Elephant. Let’s get started.

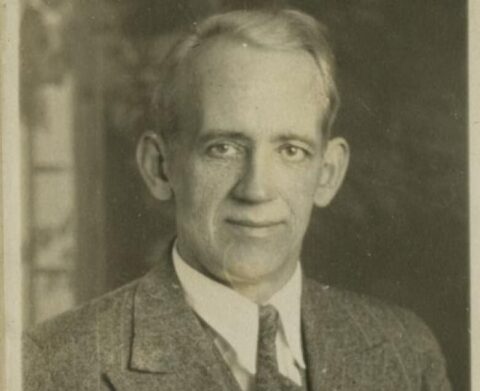

Charles “Charlie” Thorson was born in Winnipeg on August 29, 1890, to immigrant parents from Iceland. He and his older brother Joseph were brought up speaking Icelandic and English and would go on to be significant figures in the mid-20th century for very different reasons.

During their lifetimes, Joseph’s career overshadowed that of his younger brother. After finishing his studies in Manitoba, Joseph became a Rhodes scholar (attending Oxford from 1910-1913, becoming a lawyer). He practised law for a short time in London and then returned to Manitoba where his career took off. He served as a Captain with the Canadian Expeditionary Force during World War I in France from 1917 to 1919. After returning to Manitoba, he worked as a professor with the Manitoba Law School (becoming Dean from 1921-1926). In the late 1920s, he became a federal politician, being elected as a Liberal MP for Winnipeg South Centre in 1926 (before losing his seat in 1930). However, he was re-elected as the member from Selkirk in 1935 and again in 1940. He was the federal Minister of National War Service from 1941-1942 before being appointed President of the Exchequer Court of Canada (which became the Federal Court of Canada in 1971). Joseph would serve in this capacity until 1964. The elder Thorson brother had an impressive career that had longstanding implications for the makeup of Canada’s judiciary.

Charlie went in a different direction than his older brother and would eventually become a significant pioneer in North American animation prior to World War II. After completing his formal schooling, he worked odd jobs in Winnipeg (and later Gimli, where his family moved in 1912, with his father becoming mayor a couple of years later). He spent much of his time with a circle of artist friends and although he was never formally trained as an artist, he did dabble in political cartooning for some Manitoba-based Icelandic language newspapers at the time. He married his first wife in 1914, but she died from tuberculosis shortly thereafter (as did their toddler a few months later). The shock of losing his young family led to Charlie spending much of the rest of the decade living as a tramp bouncing around various locales in Western Canada.

He returned to Winnipeg in the 1920s, where he married his second wife and had additional children. This second marriage ended in divorce in 1931. It was during this time period that Charlie started working for the renowned studio Brigden’s of Winnipeg as an illustrator for T. Eaton Co. (Eaton’s) catalogues. At this time all products in the catalogue were illustrated, which allowed the younger Thorson brother to hone his craft (though he specialized in drawing jewellery and saddlery).

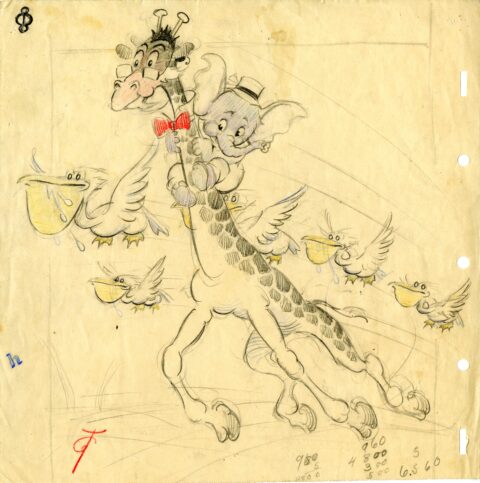

When he was around forty-five years old, Charlie Thorson took a bet on himself and moved to Hollywood to seek employment in the burgeoning animation industry. From 1935-1937, Charlie worked for Disney, which was producing short animated films as part of the Silly Symphonies line. Thorson also worked as an animator and character designer for various Silly Symphonies shorts, including 1937’s Little Hiawatha and the original Elmer Elephant in 1936.

At this time, Disney was heavily invested in its first feature film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Thorson later claimed that Snow White was based on a waitress working at Winnipeg’s Wevel Café named Kristin Solvadottir and also claimed that he designed six of the dwarfs for the film. This runs counter to Disney’s official history of the movie (though historically Disney has not credited its animators in any capacity). Supposedly, early sketches have survived that support Charlie’s version of events. After the film was completed, Thorson found that he was not credited for his contributions. Angered, he left Disney to work for MGM briefly before being offered a job as one of the main character designers for Warner Brothers. The company saw Thorson as an important animator who could help them compete with Disney.

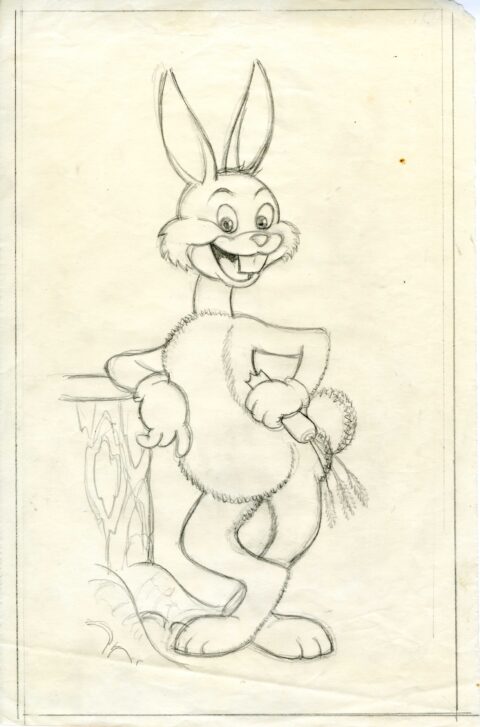

It was at Warner Brothers where Charlie Thorson made his most important contributions to the history of animation. It was during this time that Charlie completely redesigned the Warner Brothers look to be heavily based around anthropomorphic animals. Working with director Chuck Jones, he helped to create or redevelop mainstays of the Merry Melodies series such as Elmer Fudd. His most important contribution to the company was participating in the redesign and naming of Bugs Bunny. Somewhere along the way, Thorson also earned the nickname “Cartoon Charlie.”

Despite this, Thorson’s employment at Warner Brothers was short-lived. He left the company due to what is believed to be a copyright dispute by the end of 1939. He then worked for the Fleischer brothers from 1939 to 1940 where he redesigned characters from both Raggedy Anne and Popeye. In 1941 he worked for Terry Tunes where it is assumed that he was involved in the creation of Mighty Mouse. Along the way, he had a mental breakdown, which affected his ability to earn a living in the animation industry. During the remaining war years, Thorson worked in advertising as a commercial artist in order to pay the bills.

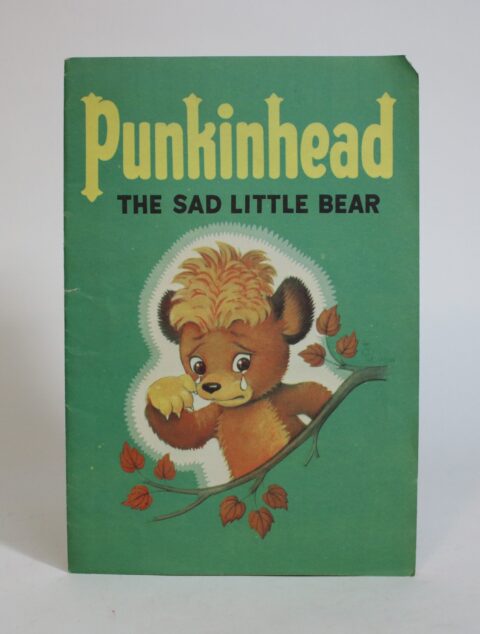

He returned to Winnipeg in 1946, where he brought his experience in commercial art back to Eaton’s. At the time, Eaton’s was in the process of developing a toy bear with England’s Merrythought toy company. Thorson designed the character, Punkinhead “the sad little bear,” which was quickly developed into the company’s mascot and appeared in numerous children’s books over the next couple of decades.

The character became synonymous with Eaton’s Christmas catalogues and Thorson’s design would be depicted in a wide variety of children’s merchandise until the 1980s. Punkinhead became a mainstay at the Toronto Santa Claus parade and was even depicted on clothing, watches, houseware, and dinnerware. Strangely, as far as I know, the character never appeared in a Canadian comic book. This is likely due to its popularity emerging during the era between FECA and the Canadian Silver Age. Nevertheless, the mascot was big business in Canada for much of the second half of the 20th century. As Eaton’s started to decline in the 1980s due to unsuccessful attempts at expansion (and competition from companies such as Sears and Zellers), Punkinhead was usurped in popularity by Zellers’ own toy bear/mascot, Zeddy (which debuted in 1986) as the century came to an end.

Punkinhead was so lucrative that it should have made Charlie Thorson a rich man. However, according to historian Gene Waltz, Thorson got drunk at a party at the Fort Garry Hotel and threw a punch at an Eaton’s executive. He was immediately fired. Feeling slighted by Eaton’s, he sold his rights to Punkinhead back to the company for $1. Typical Cartoon Charlie.

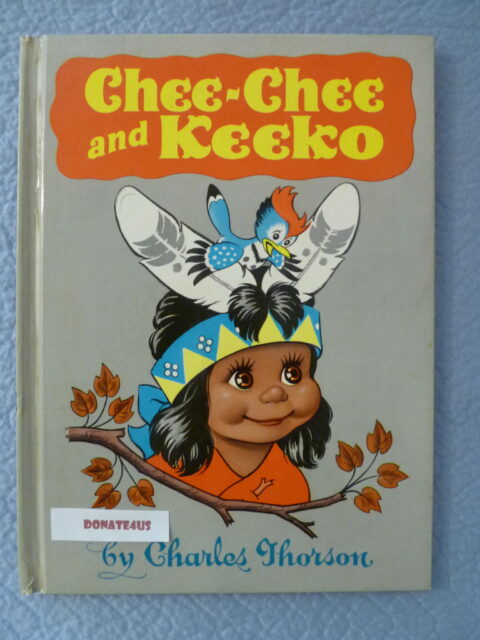

Given that Punkinhead became an incredibly popular children’s book character, it only makes sense that Thorson would attempt to create his own children’s books after his abrupt exit from Eaton’s. He released two popular children’s books, 1947’s Keeko and 1951’s Chee-Chee and Keeko. Channelling his earlier work on Little Hiawatha for Disney, the books depict the exploits of a young First Nations child’s interactions with forest animals. Unfortunately, Thorson was never fully remunerated by the publisher.

Thorson’s final major contribution to the history of cartooning and animation was his redesign of Elmer the Safety Elephant. The original idea for the character came from when then-mayor of Toronto, Robert Hood Saunders, was visiting Detroit and learned of the city’s program to teach safety to elementary school children. The program, sponsored by the Detroit Times, featured a cartoon patrol boy as its mascot.

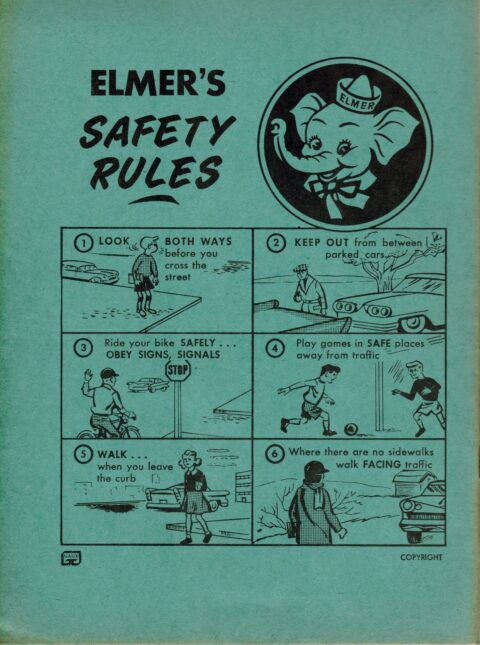

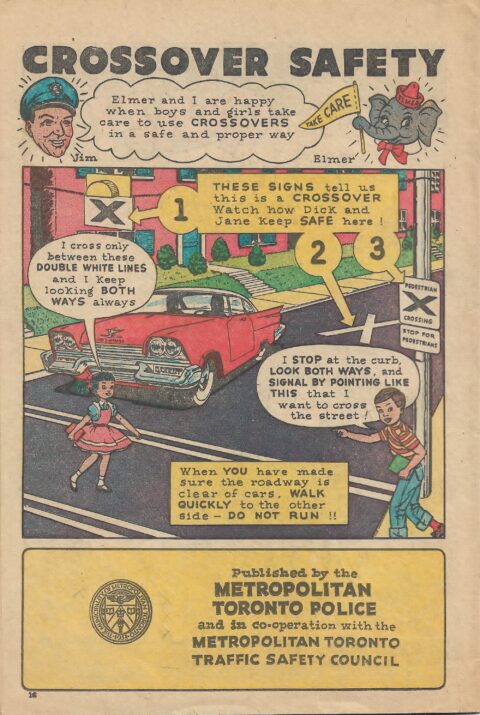

Mayor Saunders subsequently approached the editor of Toronto’s newspaper The Telegram about starting a similar initiative. They decided on using an elephant as their mascot because of the old cliché that an “elephant never forgets.” The original Elmer was a standard jungle elephant. Some sources say that Thorson was hired to revamp the character in 1948, while others say this occurred in 1952. Either way, Thorson’s version of the character became recognizable in Ontario (and Canada in general) throughout the 1950s with its six safety rules that were designed to prevent children from getting involved in pedestrian/motor vehicle accidents.

Demand became so high for Elmer that The Telegram authorized the Ontario Safety League to administer the program to the rest of the province. The character went nationwide in 1962, with the Canadian Highway Safety Council assuming control of the program at the national level. Like Punkinhead before it, Elmer ended up having various amounts of merchandise associated with it and its own songs. Merchandise included songbooks, toys, patches, stickers. When The Telegram ceased publication in 1971, it transferred the rights to the character to the newly established Canada Safety Council (which retains the rights today). This led to a series of animated public service announcements during the decade that helped solidify the message “look both ways before you cross the street,” in the consciousness of Canadian children. The character was revamped sometime in the past couple of decades and continues to be used today.

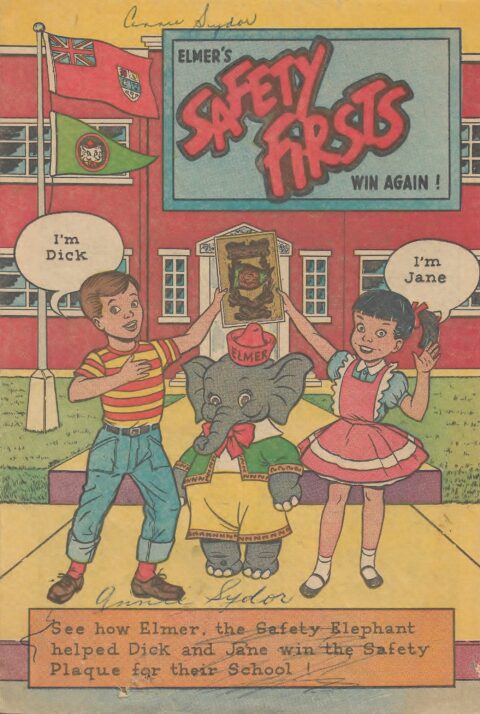

Most important for my purposes is that Elmer was the only character associated with Thorson to appear in comic book form. In addition to appearances in The Telegram, Elmer the Safety Elephant appeared in an undated pamphlet released by the Metropolitan Toronto Police Department and a comic book that was published by Ganes Productions at some point during the early Canadian Silver Age.

My best guess is that this comic was released in the early-to-mid-1960s because of it being produced by the Metropolitan Toronto Police in conjunction with the Metropolitan Toronto Safety Council (rather than having a provincial or nation-wide release). This is amongst the rarest comics from Ganes Productions, with the specimen that I have in my collection being the only one that I have ever encountered. This does not mean that it is the most valuable comic created by Ganes Productions, as that distinction is held by the rarely seen comic about venereal disease called V.D.

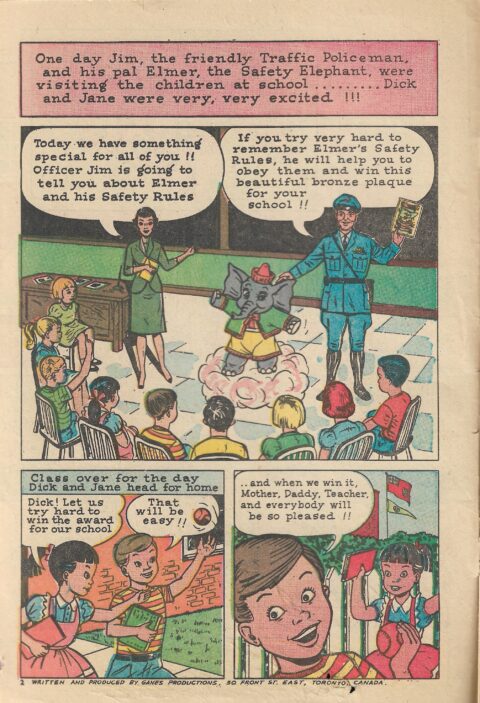

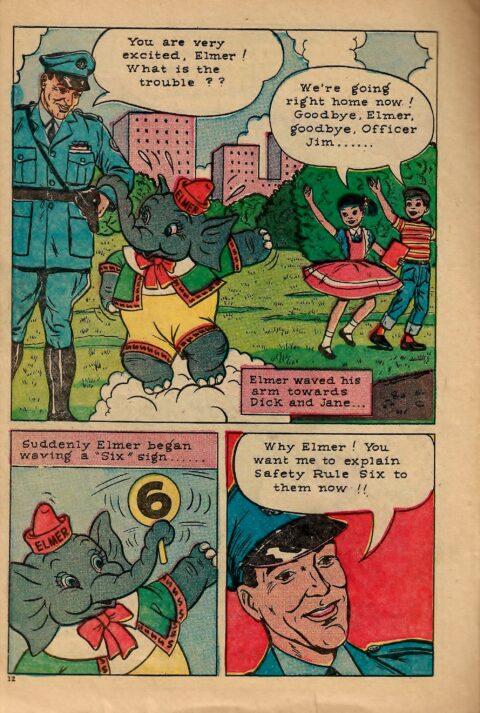

The comic is effectively an expanded version of the six safety rules explained by Elmer and a traffic policeman named Jim (who looks almost exactly the same as a character named Constable Johnny Canuck, who stars in what I believe to be one of the earliest comics released by Ganes, the IGA Safety Guide for Bicycle Riders). Two young children, named Dick and Jane, accompany Elmer and Jim as they learn about traffic safety and try to win a safety award for their school.

The narrative in the comic is, unsurprisingly, quite simplistic. The artist(s) and writer(s) are not credited either, which is typical for Ganes comics. What is certain is that Thorson was not involved in this project. It is yet another example of one of his creations (or co-creations) taking on a life of its own in the broader pop culture landscape. The comic ends with Dick and Jane winning the award for their school with Elmer and officer Jim happy to have taught the youngsters about safety.

Despite his importance in the history of animation in the United States and his role in creating Punkinhead and redesigning Elmer the Safety Elephant, Thorson struggled to find work in the early 1950s. His distinctive style had changed the way that Disney, MGM, Warner Brothers and other studios presented their characters, while Punkinhead made Eaton’s an incredible amount of money and Elmer taught generations of Canadian children about traffic safety. Thorson, unfortunately, never got to experience any of the financial windfalls afforded the companies who owned his creations.

For Canadian comic collectors, the closest thing to a Thorson comic is Elmer’s Safety Firsts Win Again! Certainly, many of the characters that he worked on or created for American animation studios were depicted in comic books in the United States beginning during the Golden Age (with comics featuring characters such as Bugs Bunny being reprinted in Canada during the FECA period). However, his most iconic Canadian character, Punkinhead, has never appeared in a Canadian comic book that I have been able to identify, which makes this comic from Ganes Productions the only such comic from Canada from the era to feature a Thorson character.

Thorson retired in 1956 and moved to British Columbia to live with one of his sons. He died in 1966, but it would be decades before he would receive the attention in his home country that he deserved thanks to the research of Gene Waltz and the preservation of his material at the University of Manitoba. Today, Thorson finally is remembered as the important artist and creator that he was, rather than the younger brother of a well-known politician.

See: Cartoon Charlie: The Life and Art of Animation Pioneer Charles Thorson by Gene Walz.

(with the assistance of Dr. Stephen Thorson)

Great Plains Publications, Winnipeg MA, 1998

CORRECTION: I misspelled Gene Walz’s name as “Waltz” in this column. I had also intended to included a reference to his book, which Brownie mentions here, but accidentally omitted it from the final draft. As such, thanks Brownie for sharing that information for my readers. My apologies, everyone.