When I discussed Fuddle Duddle during last month’s column, I highlighted that the characters Captain Canada and Beaver Boy were the first attempt at creating nationalistic Canadian comic book superheroes since the end of the Golden Age. Despite Captain Canada and Beaver Boy being parodies of the superhero genre, the creation of the characters was the beginning of a long line of nationalistic superheroes that would come to dominate the Canadian Silver Age such as Captain Canuck, Northguard and Northern Light. There is one English-language superhero from the Silver Age that is so bizarre that it truly breaks the mold: Captain Newfoundland. In order to understand Captain Newfoundland, the comic book character, one also has to have an understanding of Captain Newfoundland the man, Geoff Stirling. Today, I will outline the unique context that led to one of the most-talked about, but rarely seen characters from the Canadian Silver Age.

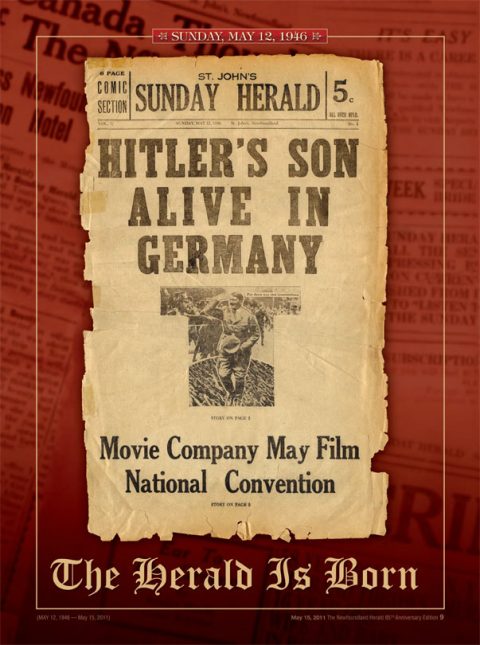

Geoff Stirling was born in St. John’s in 1921 in the then Dominion of Newfoundland. As a young man he was an accomplished track and field athlete, attending Tampa University in Florida on a full athletic scholarship. After his track and field career ended, he founded The Sunday Herald in 1946, which became Newfoundland’s premiere tabloid newspaper (and still exists today as The Newfoundland Herald). By 1948, Stirling had taken an interest in politics and was one of co-founders of the Economic Union Party (EUP). Said party advocated for Newfoundland joining the United States during the 1948 Newfoundland referendums that resulted in the dominion becoming Canada’s tenth province on March 31, 1949.

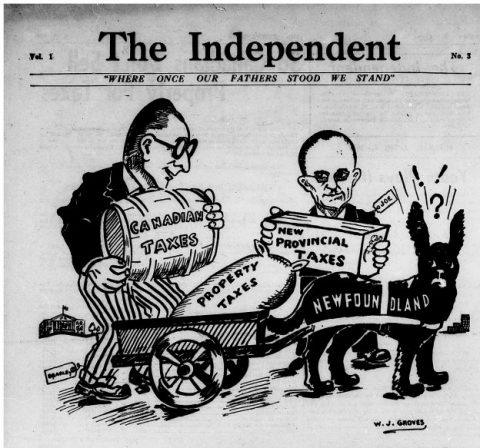

The political history of Newfoundland joining Canada is long and complex. Even though the province is home to the oldest settlement in the country, it was the last part of the colonies to establish responsible government in 1855. Newfoundland did not send any delegates to the 1864 Charlottetown Conference, nor did it send delegates to the London Conference of 1866 that led to the British North America Act. By the 1930s, Newfoundland was on the brink of economic collapse and the British took control of governing the dominion in 1934. During WWII, Newfoundland experienced an economic boom due to the establishment of American military bases in the territory. After the war, the United Kingdom decided that it wanted to sever ties with Newfoundland as a cost cutting measure, which led to the referendums. The Mackenzie King government was only willing to help Newfoundland if the territory joined the confederation. At no time was joining the United States a referendum option, as the British refused to allow one of their colonies to join the USA. Future premiere Joey Smallwood slammed the EUP as being anti-monarchist, disloyal and anti-British. Despite being popular amongst the business elites of the Avalon Peninsula, the EUP failed to gain traction amongst the wider population. Newfoundland became the tenth province and Joey Smallwood became its first premiere.

Even though the EUP was defeated politically, the aftermath of Newfoundland joining Canada opened up various opportunities for Stirling to expand his media empire. In 1950, he established an AM radio station, CJON (now CJYQ) and in 1955 he founded the first television station in Newfoundland, CJON-DT, with Don Jamieson. Jamieson would later become a well-known politician, working as a federal cabinet minister under Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Stirling and Jamieson claimed that they were the only parties who had enough money to invest in such a project, but it is also possible that they used their political connections to open their station before CBC could.

By the 1970s, CJON-DT had become a CTV affiliate and was going by the name NBC (Newfoundland Broadcasting Company). In order to avoid confusion, the station rebranded as NTV in 1978, after the US-based NBC became available in the province on cable for the first time. The station is still called NTV today and is significant in the history of Canadian television for being the first station in the country to broadcast around the clock, twenty-four hours a day, starting in 1972. The television and print side of the business became Stirling’s main interests and by 1977, he and Jamieson had parted ways, with Jamieson taking control of their AM radio stations.

Newfoundland joining Canada enabled Stirling to build his media empire because of the new economic situation in the province. Both are important factors for understanding how the comic character Captain Newfoundland came into existence. The final element to this backstory that helps to contextualize this has to do with Stirling’s obsession with mysticism. Nowhere was this more apparent to Stirling’s audience than during the early morning hours of his television broadcasts after NBC/NTV started round the clock programming.

Stirling was profoundly influenced by 1960s psychedelic counterculture. In 1963, Stirling launched the first English language FM radio station in Quebec, Montreal’s CKGM-FM (now CHOM-FM), which for six years played easy listening instrumental music. Stirling changed the format of the station to album-oriented rock in October, 1969. CKGM-FM became Montreal’s counterculture radio station, hosting multi-day Beatles marathons, live meditative chanting and even divinations.

This change did not occur in a vacuum. According to Stirling’s son, Scott, he and his father met John Lennon while on vacation in London, UK, with the elder Stirling interviewing the former Beatle at Apple Studios. Scott Stirling even claimed to The Globe and Mail that his father invited John Lennon and Yoko Ono to Montreal, leading to their “Bed In” where they recorded Give Peace a Chance. By the time that NBC/NTV started to broadcast twenty-four hours per day, Geoff Stirling was not merely obsessed with mysticism: rather, he had become one of Eastern and Atlantic Canada’s main media brokers/providers of the counterculture movement.

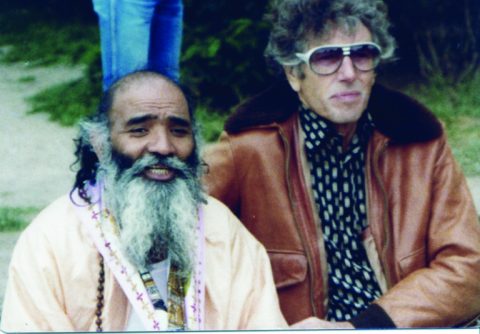

Rumours of Stirling’s adventures circulated, some of which are hard to believe (such as the time he supposedly injected gold into his veins as a possible cure for arthritis). On the other hand, his trip with former rival Joey Smallwood to Cuba for a prearranged meeting with Fidel Castro that was abruptly cancelled is well-documented and led to the documentary Waiting for Fidel in 1974. In 1975, he travelled to India to spend time at Swami Shyam’s ashram, where he engaged in daily meditation, yoga, veganism and LSD. This solidified Stirling’s own mysticism and he would write his own spiritual manifesto, In Search of a New Age, as a result. In fact, 1970s and 1980s NBC/NTV late night telecasts often involved Stirling going on hours long rants about his mystical beliefs. On occasion, NTV still airs specials spouting new age philosophies (including this one that shows part of Stirling’s trip to India). In the background of this improbable life is a man who loved and promoted Newfoundland. Indeed, the eccentric world-travelling counterculture mystic media mogul eventually took on the moniker “Captain Newfoundland” himself.

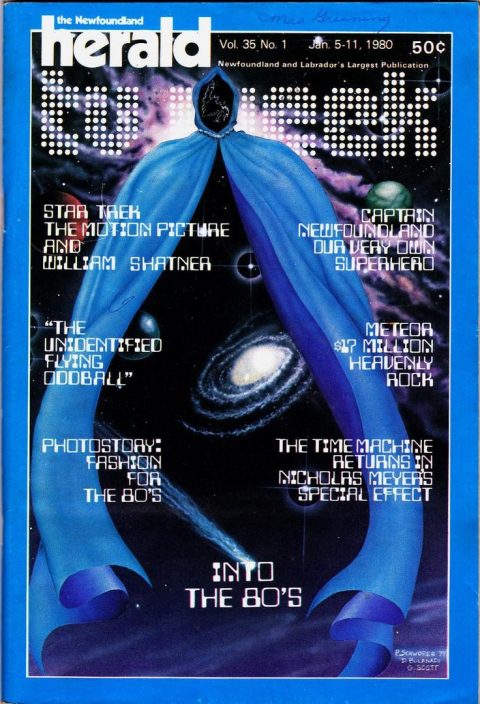

Stirling ended up resisting the CRTC after its creation in 1968 (he felt that Newfoundland audiences were more interested in American television than Canadian content) and he feared that if he ever sold NBC/NTV to a national company that Newfoundland would lose its sovereignty. One area that he was critical of was comic books. He felt that there were no Canadian superheroes (though he was not entirely correct). That said, Stirling’s vision for a Canadian superhero was one that would help people unlock their inner strength and consciousness. The result, which he created with his son, Scott, and Filipino artist Danny Bulanadi (who is better known as an inker for Marvel and DC) was as much time-travelling psychedelic cosmic-guru as it was superhero: Captain Newfoundland (who also used the aliases Captain Atlantis, Odin and Samadhi throughout the series).

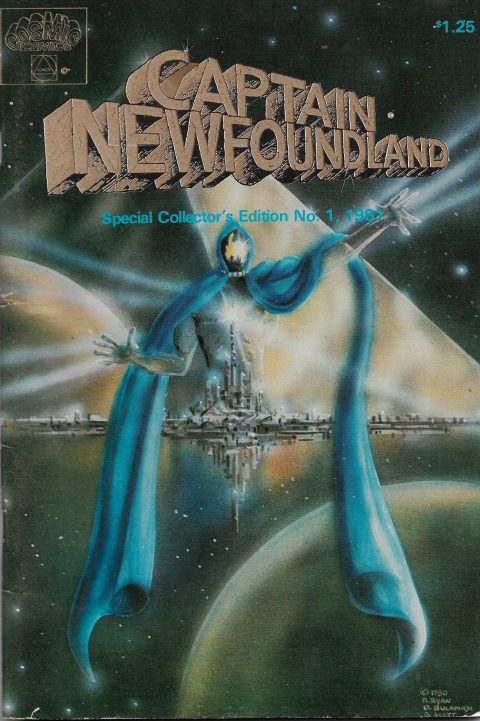

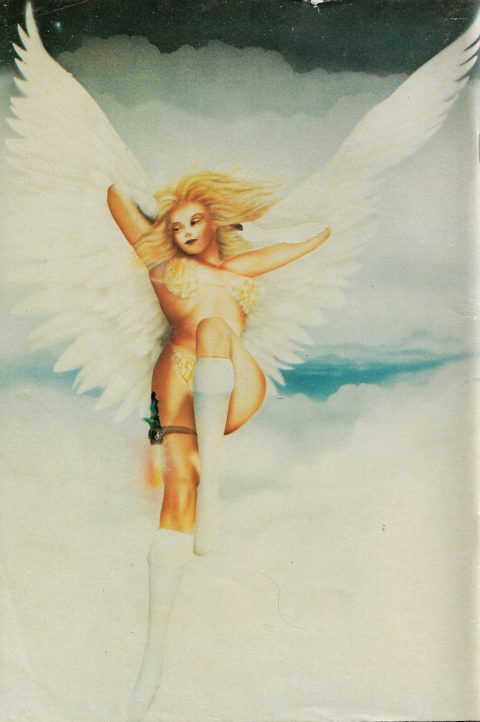

The character debuted in The Newfoundland Herald in 1979. The strips would be reprinted under the label Cosmic Comics in 1981 in the 124-page Captain Newfoundland # 1. This comic has a glossy full colour cover, but the interior pages are black and white. A second volume, the graphic novel Atlantis was printed in 1983 by Apache Communications (one of Stirling Communication’s many imprints). This full colour graphic novel is 104-pages in length. Interestingly, the Stirlings are credited together under the pseudonym Geoffrey Scott in both volumes. Noted Peruvian painter, Boris Vallejo, contributed art to this second volume. Vallejo still has a fan following for his painted fantasy covers for books by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert E. Howard and John Norman, among others. Since Vallejo signed his works with his first name, he is usually referred to as Boris by collectors. We had also uncovered references to a third volume, The Legend of Captain Atlantis, which may have been released in 1989. However, as of this writing, we have not been able to find concrete evidence that said comic exists.

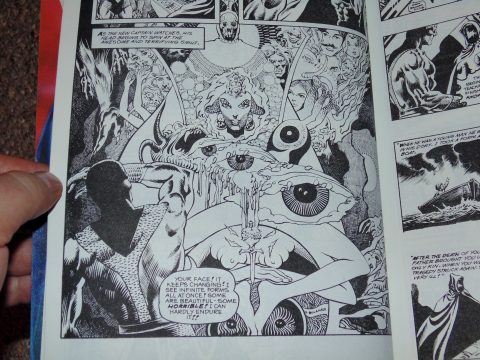

The comic narrative explains that originally Captain Newfoundland’s species came to Earth several millennia in the past, teaching the Egyptians how to build the pyramids and the Indians how to become one with the universe. As a side note, this ancient alien explanation for religious beliefs and advanced technology was popular amongst new age practitioners in the 1970s due to the works of Erich von Däniken. In the narrative, these extra-terrestrials founded their own civilization on a continent that existed somewhere between North America and Europe, only for much of the continent to be destroyed over time. The kingdom they formed was Atlantis and its only surviving landmass was its tip—present day Newfoundland. As a result, Captain Atlantis takes on the moniker Captain Newfoundland in the present day.

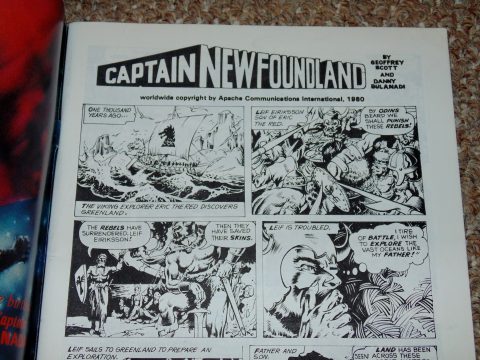

In the original comic strips and the reprinted comic book, Captain Atlantis encounters Leif Erikson and his Viking brethren after they establish a colony on Newfoundland. The Vikings are threatened by the alien’s presence and attack, but the Captain transforms into Odin and kidnaps Erikson. Once the two are alone, the Captain reverts to his regular form and explains that he is a descendant of the ancient alien colonizers and then uses his powers to save the Vikings from an imminent storm. Erikson wonders aloud what the future holds for the Vikings and this new land, so Captain Atlantis transports him to the future using his time travel powers and shows him that the world has changed, but in many ways has also stayed the same. Since time travel requires a great amount of energy, the Captain leaves Erikson with his apprentice, Golden Dove, so that he may become one with the universe and recharge his energy. Afterwards, he returns Erikson to his own time.

The Leif Erikson story lasts nineteen pages and then immediately switches to a story where Captain Newfoundland retrieves his son, Jesse, from the present day and transports him to the futuristic City of Za. Jesse is given a super-powered suit and is given the name, Captain Kundalini. The guru narrative is explicit in this story, as the chapter involves Captain Newfoundland training Kundalini with the help of Golden Dove. The training is more mystical than anything else. Looming in the background in present-day Newfoundland is a flying saucer that is hovering over the province, which NTV reporters are tracking. Kundalini makes contact with the aliens, who explain to him some of the secrets of the universe. Captain Newfoundland appears and the aliens ask him to explain how they can achieve “oneness.” Elsewhere, the villain Black Star plans to conquer the universe (though we do not see the character again in the comic).

After the heroes end their encounter with the aliens, Captain Newfoundland reveals the Captain Canada suit to Kundalini, explaining that the wearer will be Canada’s own superhero. Captain Newfoundland reveals that he has already selected the person who will wear the suit and we are introduced to Daniel Eaton, who is sitting in a jail cell. Weeks pass and Eaton has been released. The remainder of this chapter focuses on Captain Newfoundland convincing Eaton to become Captain Canada. This chapter lasts for fifty-four pages.

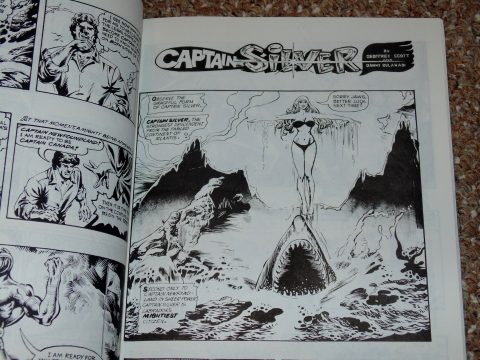

The second chapter, called “Captain Silver,” introduces us to the titular female hero who is the “strongest descendant from the fabled continent of Atlantis.” Golden Dove approaches Captain Silver and explains that she has been summoned to the Pyramid by Captain Atlantis. It is revealed that there are thousands of super-powered descendants of Atlantis in suspended animation in the Pyramid and that Golden Dove had asked for permission to find Captain Silver because she had been in suspended animation for centuries. Captain Silver had been out of suspended animation for a year and was summoned to return for tests to see if she is healthy. If so, the others will be released from suspended animation. Five pages into the chapter, the story is interrupted by a “Cont. after 8th page following” statement.

The third chapter of the comic, called “A Day with Captain Newfoundland” is an eight-page story that involves Captain Newfoundland bringing a child, Dale, to the astral plane late at night. When the child awakens in his bed and tells his parents about the experience, they don’t believe him.

The comic then returns to the Captain Silver story and we learn that she had been sent to become New York City’s hero. Elsewhere in New York, a mad scientist has convinced his henchman, The Cat Prowler, to undergo an experiment that will lead to him being infused with the power of a lion. The end result is an anthropomorphic creature called Lion Man who instantly starts wreaking havoc. Much of the chapter deals with Captain Silver defeating Lion Man. After she does, the narrative abruptly switches to the past, where we learn the origin of Captain Silver. In Atlantis she was known as “The Silver Warrior” and teamed up with Captain Atlantis to protect the continent. Unfortunately, the story ends without the reader learning whether or not her year outside of suspended animation has had a negative impact on her health. The chapter is fifty-eight pages long and concludes the comic.

I must admit that when I first learned of Captain Newfoundland, I was both surprised and confused. The character is not really a superhero per se and, unlike most of the comics that were being created during the first half of the Silver Age (both French and English), the character does not seem to take any influences from American superhero, science-fiction or even underground comix. The reason for examining the history of its creator, Geoff Stirling, is that it contextualizes the very reasons behind the existence of the character. This is the story of two Captain Newfoundlands: the cosmic space-guru comic book character is the embodiment of the mystical and new age philosophies of the media mogul himself, who fancied himself as just such a guru.

The story does not end here. Next month, I will delve into the graphic novel Atlantis and its main character Daniel Eaton/Captain Canada, the legacy of Captain Newfoundland and the scarcity/value of these comics. Stay tuned!

Great job, brian, on helping clarify and contextualize an obscure and eccentric corner of Canadian comic book history. I can’t think of many people, here in the central parts of Canada, who were aware of this comic cosmology unfurling on the ‘Rock’ at the end of the ’70s. I wonder what the print runs and distribution of the Captain Canada comic and the Atlantis graphic novel, in fact,were? Why is it that the very most interesting parts of Canadian comic book history are buried in such obscurity and the treasures unearthed so bloody rare and generally unatainable? You know, I never consider myself a ‘historian’ as much as I consider myself a ‘treasure hunter’ when it comes to examininge WWII Canadian comics and you’ve found a nice little chestful here.

Hi Ivan,

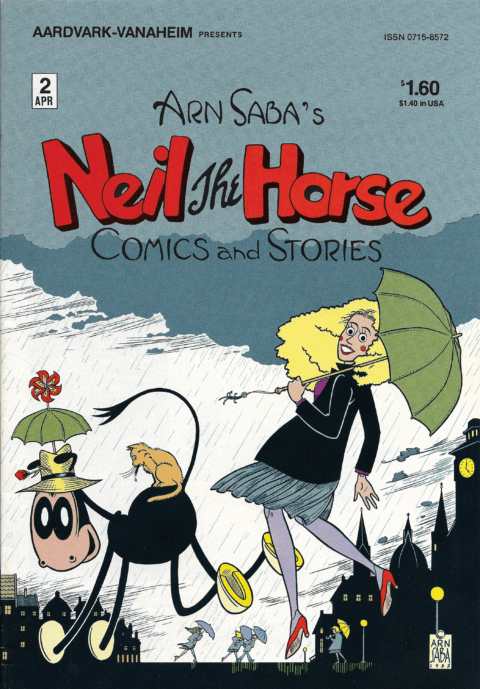

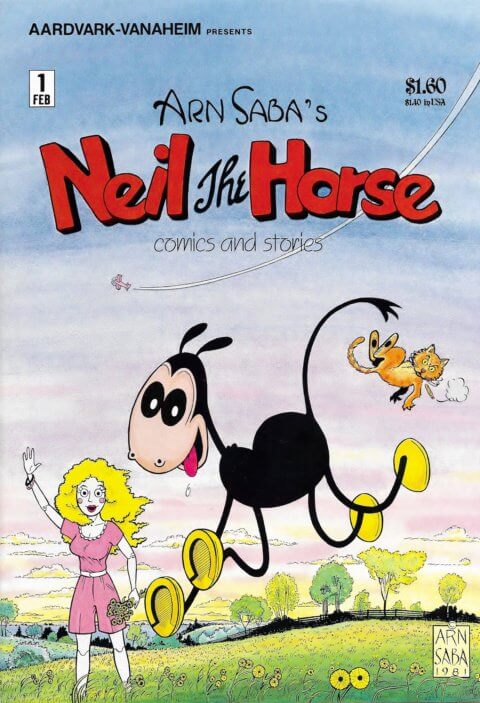

Thanks for commenting and for your kind words. It is quite astonishing just how many obscurities were produced during this era. Some of the comics we have uncovered are so rare that only a handful exist in private collections and university archives. This is particularly true of some of the Underground Comix that I have not covered yet. Consider that the most famous of all Canadian comics from this era, Cerebus # 1, only had a print run of 2000 and that John Byrne’s first published work (which may be the most valuable comic from the era), 1971’s ACA Comics: The Death’s Head Knight, had a print run of 500. We have come across comics that have had print runs much lower than these. This is the result of individuals printing their own comics in small batches, which makes the history difficult to research and the treasure hunt fruitless in a number of cases.

I do not have the print run totals for Captain Newfoundland # 1, but Atlantis had a run of 10,000 copies. I had been planning to save this for next month, but I suspect that Captain Newfoundland # 1 had a similar run. The Stirlings had the knowledge, skills and production capabilities to print these in large quantities. However, it does not seem that these were made available outside of Newfoundland (at least in any significant number). So, despite their apparent scarcity, it is possible that someone is sitting on a large pile of these or that a batch is hidden in storage somewhere. Both comics are coveted in certain circles and I will wait to discuss pricing until my next column.

Thanks again,

brian

Great, bizarre stuff. Love it.