When CEO Steve Job introduced the world to Apple’s new tablet device in January, many comic book fans and industry insiders questioned how the iPad would impact comics. Some hailed it as the saviour of the industry, while others stated that not much would change, at least for now. This article will be presented in two parts. The first part will discuss the behaviour of comic book fans and collectors as consumers. The second part will analyze how this device – and the switch from direct to digital distribution – will affect how comic book fans and collectors will collect comics.

Introduction:

Culture is described by Solomon, Zaichkowsky, and Polegato (2008) as “society’s personality” (p. 461) or the “accumulation of shared meanings, rituals, norms, and traditions among the members of an organization or society” (p. 461). The way in which we understand the world around us is influenced by our culture. As such, culture is comprised both of intangible and tangible things and has a profound effect on the choices that consumers make. In other words, “a consumer’s culture determines the overall priorities he or she attaches to different activities and products. It also mandates the success or failure of specific products” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 461). Therefore, in order to understand the way consumers behave the way they do and why they make the choices they do, a successful marketer needs to understand the culture out of which the consumer understands the world around him/her.

However, understanding the overall culture of a society is not enough. Found within the overreaching normative culture of any society, there are a number of distinct subcultures to be found. Simply stated, subcultures are groups of like-minded individuals whose norms, values, and customs are distinct from that society’s mainstream culture (Hebdige, 1984). Some examples of these types of subcultures are comic book fandom, Trekkies, Goth, Hip Hop, Emo, and Furry. Subcultures can affect consumer choice every bit as much as mainstream culture can, especially when it comes to predicting the success of a new product.

In terms of “Comic fandom, and the practice of comic-book collecting in particular, is evidence of the complex and structured way in which avid participants of popular culture construct a meaningful sense of self” (Brown, 1997, p. 13). In this paper, I use the term comic book collector and comic book fan interchangeably. While they have been discussed in the literature two unique concepts, the distinction between the two has blurred significantly in recent years to allow for the substitution of one term for the other. Historically, the distinction has been made based on the level of fandom participation between the two groups. Comic book fans are comic book collectors who participate in fandom. Collectors are typically older and do not participate in fandom (though they have usually participated in it in the past).

While many herald the release of Apple’s tablet computer, the iPad, in spring 2010 as the great saviour of the beleaguered comic book industry, this study has found that this assertion is unsubstantiated. On the one hand, there is evidence to demonstrate the potential of digital distribution channels, like the iPad, to help revitalize the industry. On the other hand, there are a number of identifiable challenges facing the comic book industry in terms of adapting its printed content into digital formats. In other words, this report determines that digitizing comic book content is a promising future distribution channel; however, there are still a number of logistical challenges that this channel presents that need to be addressed.

This study will first discuss comic as a form of sacrilized consumption and argue that the participation of fans and collectors in comic book fandom as a form of ritual and rite of passage. I will then provide a brief history of the Comics’ Code Authority and the changing distribution channels that resulted in direct market distribution – both of which are responsible for shaping the industry into what it is today. Furthermore, I will provide a snapshot of the current demographics as well as explore the psycho-social and mythic functions comic books perform within society. Following this, I will discuss and analyze fan participation and fan communities. The movement of both of these things on to the World Wide Web has the potential to increase the level of diversity in terms of gender and race within the consumer demographics.

Following this situational analysis, I will discuss the potential of the iPad as it relates to its role as an e-reader, as a part of the Web 2.0 phenomenon – including the democratization of technology and the generation of user-generated content, and the potential for increasing consumption via digital distribution channels. Finally, I will discuss the challenges facing both publishers in successfully implementing the iPad – as it currently stands – including issues with the Apple App Store, the cost associated with digitizing content, and the act of collecting comics and being counter to the digital distribution channel it promotes.

Collecting as Sacred, Collecting as Ritual

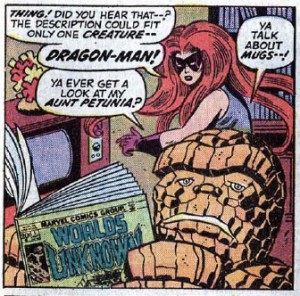

The definition of a ritual “is a set of symbolic behaviours that occur in a fixed sequence and that tend to be repeated periodically” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 467). Ritual experiences that are ascribed to comic book collectors and fans are subculturally-, group-, and individually-based rituals. Examples of the subcultural rites of passage include the process of becoming a fan, and cultural rituals include events like Free Comic Book Day (FCBD), which is an annual event held on the first Saturday of May. Another example of a cultural ritual is comic book conventions. While smaller conventions are typically held three or four times a year, there is usually one or two large conventions that are held annually and are places where members typically congregate. Group and individual rituals are combined during the weekly trek to the comic book store on Wednesdays (known as New Comic Book Day) to purchase comics. Brown (1997) argues that “Comic fandom is rather unique in relation to other popular culture fan communities because it is almost exclusively centered around a physical, possessable text” (p. 22). It is the centrality of the physical artefact within collecting that differentiates comic book fandom from other types of fandom (such as science fiction fandom, fantasy fandom, or a number of different fandoms associated with individual texts like Star Wars and Harry Potter).

Comic book collecting is a form of sacred consumption whereby comic books and their associated merchandise “are set apart from normal activities and are treated with some degree of respect or awe” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, 475). Furthermore, the ritualistic aspect of comic book fandom demarcates the fan’s local comic book store where he/she is a regular as a sacred place. Unlike a religious or historical building, a comic book store is a normal retail space found within “the profane world and imbued with sacred qualities” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 475) by the fan or collector. However, it is not only the space that is scared but also the comic books themselves. Objectification refers to the process by which comic books come to “take on a sacred meaning” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 477) for comic book fans and collectors. This process of sacrilization occurs during the process of physically collecting comic books. Searching out, travelling to the store, acquiring a new comic book and adding it to his/her collection – often reorganizing and displaying them – are all parts of a process that transform a profane object into a sacred one. This new acquisition “takes on a special significance to the collector” as the process by which the object is obtained occurs systematically and rationally – though there is an emotional component to it as well (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 477).

At the store, fans and collectors usually congregate to discuss the previous week’s offering and to speculate on the current week’s releases. In this case, I define group loosely, consisting of two or more individuals. This process can take anywhere from minutes to hours, depending on the desired level of individual engagement and the ability (such as time and inclination) to participate in these discussions. These discussions serve an important symbolic function within comic book fandom: “Knowledge and the ability to use it properly amounts to the symbolic capital of the cultural economy of comic fandom, but it is the comic book itself that represents the physical currency” (Brown, 1997, p. 22). This knowledge forms symbolic capital for the individual who has acquired it and communicates it. Expanding on Bourdieu’s notion of cultural capital, Sarah Thornton (1996) argues that individuals within subcultures acquire subcultural capital – that is, the specialized knowledge about certain objects within the subculture. Furthermore, the acquisition of this knowledge raises the individual’s status within the subculture.

Ultimately, the process of physically reading the comics and then arranging and storing the individual issues are usually individual rituals that both precedes and immediately follows the group discussion of the comics – as this is a process that is repeated weekly – and occurs either in person at the comic book store or in an online forum. The discussion can be immediately following the individual rituals or can be postponed until the next week (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, pp. 467-469). In other words, owning and reading the comic book serves an individual ritual function whereas the interaction and discussion among fans is “the focal point for the entire community” (Brown, 1997, p. 22).

Ultimately, the process of physically reading the comics and then arranging and storing the individual issues are usually individual rituals that both precedes and immediately follows the group discussion of the comics – as this is a process that is repeated weekly – and occurs either in person at the comic book store or in an online forum. The discussion can be immediately following the individual rituals or can be postponed until the next week (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, pp. 467-469). In other words, owning and reading the comic book serves an individual ritual function whereas the interaction and discussion among fans is “the focal point for the entire community” (Brown, 1997, p. 22).

Becoming a Comic Book Fan: A Rite of Passage

The process by which an individual becomes a member of comic book fandom is a rite of passage, a time “marked by a change in social status” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 474). This change in social status, for comic book fans, is both a figurative and literal one. The literal change in social status is connected to the stigmatization of both comic books and their fans in North American society. Being a fan, especially of comic books, has long been perceived as being both low-culture and low-class. This is a common trait that all levels of popular culture fandom share: “Both the practice of fandom and its object of enthusiasm . . . are usually perceived with disdain within the dominant value system” (Brown, 1997, p. 13). The association of comic books as child’s literature and with the dangerous and salacious content that psychiatrist Fredric Wertham (1954) warned was corrupting children in his book, Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comics on Today’s Youth, also help to stigmatize the medium and those who are fans and collectors of it. Due to the negative associations linked to comic books, Lopes (2006) argues “Since the introduction of comic books in the mid 1930s, stigma has been associated with the form itself, its content, and its producers, creators, readers, and fans” (p. 399). As a result fans often flock to these communities in order to be able to interact with like-minded individuals. The internet has been, most recently, an important hub of fan activity as individuals can easily transgress geographic distance.

The figurative transformation that a non-fan undertakes to become a fan is similar to the three stages detailed by Solomon, Zaichkowsky, and Polegato (2008). First, the non-fan must separate him/herself from non-fans. For example, the individual first encounters comic books and decides to learn more about the medium and its narratives. The second stage finds the non-fan in between his/her fan status and non-fan status. In other words, he/she is not yet a fan. During this stage, the individual has accumulated some knowledge of comic books but does not know enough to be considered a true fan. The individual might participate in online fan communities and discussion but has not transitioned this social interaction into his/her off-line life. The third and final stage occurs once the rite of passage is complete and the individual has transitioned successfully into a fan. This occurs when he/she adopts an identity as a comic book fan and integrates that identity into his/her life (pp. 474-475; see also Jenkins, 1992). In other words, fans and “collectors devote a great deal of time and energy to maintaining and explaining and expanding their collections, so for many this activity becomes a central component of their expanded self” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 478). In other words, comic fans integrate the subculture of comic book fandom into their lifestyles and the fandom and those other members of it become an important reference group – or a group of individuals who have a “significant relevance upon an individual’s evaluations, aspirations, or behaviour” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 311), especially when it comes to purchasing decisions.

The figurative transformation that a non-fan undertakes to become a fan is similar to the three stages detailed by Solomon, Zaichkowsky, and Polegato (2008). First, the non-fan must separate him/herself from non-fans. For example, the individual first encounters comic books and decides to learn more about the medium and its narratives. The second stage finds the non-fan in between his/her fan status and non-fan status. In other words, he/she is not yet a fan. During this stage, the individual has accumulated some knowledge of comic books but does not know enough to be considered a true fan. The individual might participate in online fan communities and discussion but has not transitioned this social interaction into his/her off-line life. The third and final stage occurs once the rite of passage is complete and the individual has transitioned successfully into a fan. This occurs when he/she adopts an identity as a comic book fan and integrates that identity into his/her life (pp. 474-475; see also Jenkins, 1992). In other words, fans and “collectors devote a great deal of time and energy to maintaining and explaining and expanding their collections, so for many this activity becomes a central component of their expanded self” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 478). In other words, comic fans integrate the subculture of comic book fandom into their lifestyles and the fandom and those other members of it become an important reference group – or a group of individuals who have a “significant relevance upon an individual’s evaluations, aspirations, or behaviour” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 311), especially when it comes to purchasing decisions.

The Comics’ Code Authority and Changing Distribution Channels

During the 1940s, the comic book industry saw an increase in both the production and sales of comic books. Primarily produced for adults, comic books encompassed a wide-variety of genres, including war, romance, science fiction, fantasy, horror, and crime stories. However, the popularity of this medium would fade during the 1950s as, what started as a small grass-roots movement, successfully incited a moral panic against the form. These anti-comics crusaders condemned the medium for threatening the moral foundation and social order of society. Fredric Wertham’s (1954) polemical, Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comics on Today’s Youth, blamed comic books for juvenile delinquency, illiteracy, damaging children’s vision, and “promot[ing] a fantasy world” (Lopes, 2006, p. 401; Wright, 2001).

The constant juxtaposition of comics and the harm that they cause children created within the public a correlation between the two. This connection was further reinforced when – in order to allay the fears of the anti-comics crusaders – publishers in the comics industry voluntarily developed and enacted the Comics Code of America (CCA) in 1954. Similar to the Hayes or Motion Picture Production Code, the CCA was a self-censoring regulatory body within the industry; an action preventing any outside or government regulation (a senate sub-committee had been convened in order to determine how dangerous comic books were to children) over the industry. Simply stated, the purpose of the CCA was to police content contained within comic books to ensure that they were safe for children to read. As a result of these strict regulations, all of the major firms in the industry – especially Marvel, EC, and DC – stopped publishing any comics with adult content (especially horror and crime stories) and most adult fans of the medium abandoned it and sales declined. As sales declined, a number of genres were eliminated – publishers chose to focus on the superhero genre almost exclusively – creating another barrier to attract or retain an on-going adult readership. By 1970, most of the comic books that were published were of the superhero variety and were aimed exclusively towards children and adolescents (Nyberg, 1998; Wright, 2001).

When combined with a new generic and audience focus, the changing network channels through which comic books were distributed also resulted in a declining adult readership. Before the 1970s, comic books were sold in a wide variety of retailers and their popularity was due, in part, to the relative ease with which they were available for purchase. During the 1970s, however, the comic book industry shifted to direct market distribution; comics were sold directly by a centralized distributor to specialty or comic book shops. The largest comic book distributor in North America is Diamond Comic Distributors, Inc. Founded in 1982, they are responsible for shipping comics and comic-related merchandise from the publishers to retailers. Furthermore, as retailers were not allowed to return unsold comics for a refund, they began to actively police their ordering to save money. In other words, retailers ordered just enough comic books to meet their customers’ demand as a cost-saving measure – if they ordered too many comics, for instance, they would be left with product that would be unsellable and unreturnable to the distributor.

The industry was able to survive the downturn that accompanied the infantalization and sanitation of the form but its growth and ability to recruit new comic book readers was severely diminished as the access to the product moved outside of the mainstream. Consumers could no longer go to the local newsstand and purchase a comic book because the cover caught their eye. Consumers now had to travel to specialty retailers and impulse purchases diminished. While occasional impulse purchases never comprised a large percentage of sales, the industry also lost those individuals who could not travel the extra distance to a specialty retailer. Furthermore, one could argue that the first step in making an individual a regular purchaser of a product is to get them to purchase it once and then to keep them coming back. Therefore, while some retail sales were assured, the recruitment of future comic book readers and the retention of current readers stagnated; the larger companies simply continued to sell to a small market of fans that had remained loyal to comics (Nyberg, 1998).

During the 1980s and early 1990s, the collectability of comics as an investment created a boom in comic book sales. Special incentive and collector’s edition covers promised consumers an easy investment product and this drove both the quantity of the books sold but also the price at which speculative buyers purchased them at. The collector’s market was a direct result of the profits made from selling old comic books from the 1930s and 1940s – especially the first appearances of Superman (Action Comics #1 (June 1938)) and Batman (Detective Comics #27 (May 1939)). However, the high prices of these old, first-appearance comics reflected the scarcity of both the quality and quantity of surviving copies. Before the collector’s market exploded in the 1980s, comics were disposable products – to be read once and thrown away. As a result, there were not many surviving copies of these books and those that existed were bought and sold for higher and higher prices as demand for them increased. In the 1980s and 1990s, the sheer volume of high quality copies of the same comic guaranteed that prices would remain low (Wright, 2001). By 1993, however, the speculative market had reached its peak at $850 million, before crashing (McAllister, 2001). When the speculative collector’s market finally crashed in the mid-1990s, the industry was faced with the consequences of a flooded market. Prices dropped and there was a significant downturn in the market as the number of purchases declined. Marvel Comics – which was at the time (and still is) one of the two largest and most powerful comic book publishers in the industry (the other being DC) – filed for bankruptcy protection in 1996 (Wright, 2001).

While the market has recovered from the 1990s slump – a result of publishers adapting their products into film rather than an increase in sales of comic books – the market is still a shadow to what it once was in its prime. For example, in comic book market of the 1940s, 125 different titles collectively sold 25 million issues. Overall, “annual sales [were calculated] at nearly 30 million dollars” (Lopes, 2006, p. 400). Reflecting the changes brought about by the CCA, a popular title in the 1970s sales of about 300,000 an issue (Mackey, 2007). However, less than 30 years later, these titles only sold around 40,000-60,000 a month (Lopes, 2006). For example, in the 1940s, sales of “the most popular book, Superman, reached average sales of $1,250,000 per issue” (Lopes, 2006 p. 400). In 1995, per issue sales of the most popular comic book, Amazing Spider-Man, was only $234,000 (Lopes, 2006). Taking inflation and price increases into account, there was a drop in readership of 81.28% from the 1940s to 1997.

Despite the overall drop in sales from the 1940s, Anderman (2009), states that comic books – unlike the rest of the publishing industry – have shown remarkable resilience during the downturn of 2008 and 2009. Furthermore, “More people are reading comics than at any time during the past two decades” (Anderman, 2009). The success of comic books can be attributed both to the die-hard comic book fan and to the popularity of film adaptations which “have been catapulting comic book characters into the mainstream cultural consciousness” (Anderman, 2009). In order to capitalize on their vast collection of comic book characters, Disney Company’s 2009 purchase of Marvel Entertainment for $4 billion demonstrates that the future of comic books is more likely to be on the film or television screen rather than on the page (Phegley, 2009). Similarly, in September 2009, DC Comics’ parent company – Warner Brothers Entertainment – also formed a new company in order to adapt DC-owned characters more successfully into other forms of media (Paul Levitz, 2009).

Despite the overall drop in sales from the 1940s, Anderman (2009), states that comic books – unlike the rest of the publishing industry – have shown remarkable resilience during the downturn of 2008 and 2009. Furthermore, “More people are reading comics than at any time during the past two decades” (Anderman, 2009). The success of comic books can be attributed both to the die-hard comic book fan and to the popularity of film adaptations which “have been catapulting comic book characters into the mainstream cultural consciousness” (Anderman, 2009). In order to capitalize on their vast collection of comic book characters, Disney Company’s 2009 purchase of Marvel Entertainment for $4 billion demonstrates that the future of comic books is more likely to be on the film or television screen rather than on the page (Phegley, 2009). Similarly, in September 2009, DC Comics’ parent company – Warner Brothers Entertainment – also formed a new company in order to adapt DC-owned characters more successfully into other forms of media (Paul Levitz, 2009).

Demographics and Diminishing Sales

Based on demographic figures released between 1991 and 2009, industry insiders state that the small group of female readers has remained more or less constant during that almost twenty year period and comprises less than 10% of the total readership of superhero comic books. In other words, male fans represent over 90% of total superhero comic readership (D’Orazio, 2009; Draper Carlson 2009; Fost, 1991; Nyberg, 1998). Whether this gendered split is a function of content or form has long been debated by those both inside and outside of the industry:

For decades comic book creators had presumed that the audience for superheroes was overwhelmingly male. There had been many female superheroes over the years, but most of these seemed targeted more at adolescent male lusts than at discerning female readers. And very few successful series featured women on their own. Acknowledging that most superheroes and most comic book readers were male, Stan Lee wondered, ‘do less females read comic books because they seem to be aimed at a male audience, or are they aimed at a male audience because less females read them?’ (Wright, 2001, p. 250)

Citing an “extremely competitive nature of the comics industry” (Brown, 1997, p. 14), neither distributors nor comic books publishers rarely share their data on sales figures or the demographic composition of its customer base. Most of the information that is currently available is found in reports by bloggers who used to work in the industry and who were privy to sales and demographic information. As mentioned previously, the overall market for superhero comic books is male. It is estimated that over 90% of superhero comic book readers are male. This rate has remained fairly static over almost two decades (D’Orazio, 2009; Draper Carlson 2009; Fost, 1991; Nyberg, 1998). While comics have been positioned for children and young boys, many of those boys have grown up and still continue to collect comics. D’Orazio (2009) identifies the typical comic book consumer: “male, 20-25, video-game player, disposable income, ‘techie’, [and] single.” Similarly, Fost (1991) notes that, while adolescents still comprise a vital market, older comic fans – those who read and/or collected comics since childhood – currently make up “the core group of comic collectors” (p. 16).

In 2008, “comic books were a $715 million business in the US and Canada” (MacMillian, 2010), with the strongest increase in sales found in non-superhero graphic novels aimed at adult audiences and sold in mainstream bookstores. Over that same time, there was a decrease in demand for superhero comics. Furthermore, in the United States, there are only currently 3,000 specialty comic book retailers. This is a decline of about 68% from the some 10,000 stores in the 1990s. The decline in the number of stores has resulted in a number of places where consumers have no retail outlet to purchase comics without travelling to another city or purchasing their comics online (MacMillian, 2010).

In 2008, “comic books were a $715 million business in the US and Canada” (MacMillian, 2010), with the strongest increase in sales found in non-superhero graphic novels aimed at adult audiences and sold in mainstream bookstores. Over that same time, there was a decrease in demand for superhero comics. Furthermore, in the United States, there are only currently 3,000 specialty comic book retailers. This is a decline of about 68% from the some 10,000 stores in the 1990s. The decline in the number of stores has resulted in a number of places where consumers have no retail outlet to purchase comics without travelling to another city or purchasing their comics online (MacMillian, 2010).

Psychosocial and Mythic Functions of Comic Books

Comics serve both a psychosocial and mythic function in modern society. Witek (1999) argues that comics have a psychosocial function: the “realms of fantasy, of wish fulfilment, of projections of power, and in the ritual repetition of generic formulas” within the narrative offer a space where power fantasies can be explored safely (p. 13). The entire form and function work toward this aim; that is, identification with the superhero on the page. The need for the (assumed male) audience to identify with the superhero on the page in order to experience and engage in imaginary power plays could also be the reason why, despite our diverse and multicultural society, superheroes are regularly figured as white and male. Non-white heroes and female superheroes exist within the comic book continuum, but they are few and far between when compared with superheroes who are male and Caucasian (Mackey, 2007).

The psychosocial function of comic books is closely connected to their mythic function. George (2010), asserts that “comic books and superheroes are likely to be some of the key cultural and literary contributions made to modern society.” Solomon, Zaichkowsky, and Polegato (2008) describe myth as “a story containing symbolic elements that expresses the shared emotions and ideals of a culture” (p. 464). It is through these myths that a culture can communicate and maintain its social order in addition to prescribing ways of behaving within the world to the reader.

The psychosocial function of comic books is closely connected to their mythic function. George (2010), asserts that “comic books and superheroes are likely to be some of the key cultural and literary contributions made to modern society.” Solomon, Zaichkowsky, and Polegato (2008) describe myth as “a story containing symbolic elements that expresses the shared emotions and ideals of a culture” (p. 464). It is through these myths that a culture can communicate and maintain its social order in addition to prescribing ways of behaving within the world to the reader.

Some theorists locate the inability of the industry in attracting new readers as the result of comic books occupying a nebulous time warp where they “are heavily vested in catering to nostalgia for a fan base” (Jeet Heer, qtd. in Mackey, 2007). Instead of attracting new readers they simply pander to the same old kind of readers, refusing to grow and change as the market does. It is notable that many of those who are currently in positions of power within the industry started out as comic book fans. Are these industry leaders simply unable to respond to market demands? Peter Birkemoe (2007) argues that they may not be able to: “Companies run by fans with comics drawn by fans rarely think of catering to anyone but themselves, which unfortunately means [that] comics [are] aimed primarily at adult men who still want to read comics featuring characters suited to children’s entertainment” (qtd. in Mackey, 2007).

Comic Book Fandom: Increasing Diversity of Readership

Fandom refers to the organized set of fan activities and the social network that comprises a subculture. Fans come together based on their shared love of a popular culture text or object, in this case, their love for graphic narratives. As Brown (1997) asserts:

Rather than blind devotion, fandom is a means of expressing one’s sense of self and one’s communal relation with others within our complex society. Individual fans and entire fan communities develop intimate attachments to certain forms of mass-produced entertainments that, for whatever reason, satisfy personal needs (p. 13).

As the majority of comic book consumers are male then, it follows that, the majority of those who participate in fandom are male. However, the less than 10% of female readers of superhero comics have found a space and a voice online. Many of these female fans – most of whom self-identify as feminists – have congregated online and have formed fan communities. This demonstrates that online fan communities can be used to increase the diversity of the demographics targeted by marketing initiatives by comic book publishers. Using blog and message board postings, these female superhero comic book fans, some of whom who also work or have worked in the industry, have begun to build their own websites (such as Girl Wonder, Sequential Tart, the Occasional Superheroine, and Comics worth Reading). They are vocal, actively calling on the comic book industry to recognize them as fans, encouraging them to hire more female writers and artists, and challenging what they see as sexist and often misogynist representations of women within the pages of superhero comics. The most famous – and one of the earliest – examples of this feminist activism and call-to-action is Gail Simone’s Women in Refrigerators (War) list. A lifelong comic book fan – and now comic book author – Simone (2007) composed the list after identifying a alarming trend in superhero comic books: “that strong women in comics were to be depowered, that kind of women were to be humiliated and that loving woman were to be stuck in a woodchipper” (qtd. in Garrity, 2007, p. 74).

However, the emergence of online comic book fan communities is of no surprise. Numerous studies examining science fiction, fantasy, and cult film and television series finds that the majority of fans are women (Jenkins, 1992; see also Bacon-Smith, 1992, 2000; Harris and Alexander, 1998; and Hills, 2002). Internet fan communities transcend distance and enable female fans to connect with like-minded individuals who share similar interests. Given the small number of women who read superhero comic books, this sense of connection is especially important and ensures continued consumption of superhero comic books. Furthermore, female fans adopt these texts because – as with female manga readers – they feel a connection between the text and their own experiences. As Jenkins (1992) asserts:

For the female reader, there could be no simple, clearly defined boundary between fiction and experience since their metatextual inferences relied on personal experience as a means of expanding upon the information provided and (…) character identification be[comes] a means of self-analysis. (p. 109)

In other words, these women identify are able to find aspects of the text to identify with, demonstrating that – within superhero narratives – there is something more than just a place to engage with male adolescent power fantasies. What do these women engage with and is it possible to extend this experience outward so that other readers can get the same pleasure out of engaging with the text that these female fans do?

Participation in fan communities is a similar rite of passage process as there is in offline fandom. Individuals first enter online communities as lurkers, “asocial information gathering” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 327). During this time, they simply watch but do not participate in online fan activities. As they move into a more active and participatory role in the online fan community “the intensity of identification with a virtual communication” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 327) is dependent on how much of the individual’s self-concept is related being a fan – for example, whether or not the individual has adopted the lifestyle and identity of a fan – and whether or not the individual has formed close relationships within that community. In other words, if a fan has adopted the identity of a fan and have formed close strong bonds with other members of the community, his/her involvement will be high with the community. These individuals are known as insiders and they typically have great influence over the group. For those individuals who have adopted the identity of the fan but have fairly weak social ties are known as devotees. Minglers, on the other hand, have not adopted the identity of a fan but have made close relationships with other fans in the community. Finally, tourists do not identify with fandom and they have few, fairly shallow social ties (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 327).

Participation in fan communities is a similar rite of passage process as there is in offline fandom. Individuals first enter online communities as lurkers, “asocial information gathering” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 327). During this time, they simply watch but do not participate in online fan activities. As they move into a more active and participatory role in the online fan community “the intensity of identification with a virtual communication” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 327) is dependent on how much of the individual’s self-concept is related being a fan – for example, whether or not the individual has adopted the lifestyle and identity of a fan – and whether or not the individual has formed close relationships within that community. In other words, if a fan has adopted the identity of a fan and have formed close strong bonds with other members of the community, his/her involvement will be high with the community. These individuals are known as insiders and they typically have great influence over the group. For those individuals who have adopted the identity of the fan but have fairly weak social ties are known as devotees. Minglers, on the other hand, have not adopted the identity of a fan but have made close relationships with other fans in the community. Finally, tourists do not identify with fandom and they have few, fairly shallow social ties (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 327).

The number of women who participate in the industry and within comic book fandom has increased since the late 1970s. As mentioned earlier, female fans have become particularly vocal online, forming communities of like-minded individuals to interrogate and evaluate comic book content. Furthermore, an analysis of sales data demonstrates that women are purchasing the bound collections of monthly issues that comprise story arcs (trade paperbacks) as well as original narratives (graphic novels). In 2006, for example, North American sales of graphic novels increased by 13.27% – an increase ascribed to the increase of female consumers purchasing them (MacDonald, 2007). In fact, when sales data is closely examined, female readership of comic books and graphic novels have increased across the board – except in the genre of superheroes. Most notably, “the popularity of Japanese manga and DC comics’ edgy, sophisticated Vertigo imprint, which features mystical and fantasy series” are two specific examples of products that have been successful with women (Anderman, 2009). The increase in female readership has coincided with a change in distribution channels for trade paperbacks and manga from comic book stores and comic book conventions, both of which have been accused of being unfriendly and unwelcoming to women, and into more mainstream book retailers (DiBello, 2008). In other words, comic book stores and comic book conventions are both barriers to entry into comic book fandom. By removing these obstacles by changing distribution channels with a concomitant increase in participation in online fandom, there has been an increase in women consumers for graphic narratives.

References and General Bibliography

Allen, R. J. (2006, July 21). From comic book to graphic novel: Why are graphic novels so popular?

Anderman, J. (2009, November 14). All new adventures! The Boston Globe.

Bacon-Smith, C. (1992). Enterprising women: Television fandom and the creation of popular myth. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bacon-Smith, C. (Ed.) (2000). Science fiction culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Baig, E. C. (2010, April 1). Verdict is in on Apple iPad: It’s a winner.

Betancourt, L. (2010, February 18). Can e-readers and tablets save the news?

Bongco, M. (2000). Reading comics: Language, culture, and the concept of the superhero in comic books. New York, NY: Garland Publishing, Inc.

Brown, J. A. (1997, Spring). Comic book fandom and cultural capital. Journal of Popular Culture, 30(4), 13-31.

Bullas, J. (2010, March 14). What 3 industries is the Apple iPad threatening to decimate?

Chen, B. X. (2010a, February 19). Apple removes porn Apps from App Store.

Chen, B. X. (2010b, February 25). iPad Apps could put Apple in charge of the news.

Chen, B. X. (2010c, April 26). A call for transparency in Apple’s App Store.

Constantinides, E., & Fountain, S. J. (2008, January). Web 2.0: Conceptual foundations and marketing issues. Journal of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice, 9(3), 231-244.

Davies, C. (2009, November 5). Apple App Store stuffed with over 100,000 applications.

DiBello, J. (2008, August 15). A serious note.

D’Orazio, V. (2008, January 24). The demographics of the mainstream comic book reader [Blog posting].

Draper Carlson, J. (2008, January 24). Superhero comic readers still mostly male [Blog posting].

Dumenco, S. (2010, April 5). Just how much saving of the media does the iPad need to do, actually?

Fost, D. (1991, May). Comics age with the Baby Boom: Marketing comic books to members of the Baby-Boom generation. American Demographics, 13(5), 16.

Fusanosuke, N. (2003). Japanese manga: Its expression and popularity. Asian/Pacific Book Development (ABD) Magazine, 34(1), 3-5.

Garrity, S. (2007, November). The Gail Simone interview. The Comics Journal, 296, 68-91.

George, R. (2010, April 7). How the iPad can change the comics industry.

Griffin, M. (2010, February 8). Business publishers see iPad potential. B to B, 95(2), 1-24.

Ha, P. (2010, February 10). A comic pundit’s thoughts on the iPad and digital comics.

Hebdige, D. (1984) Subculture: The meaning of style. New York, NY: Methuen and Company, Ltd.

Hesseldahl, A. (2010, February 5). Apple’s hard iPad sell.

Harris, C. & Alexander, A. (Eds.) (1998). Theorizing fandom: Fans, subculture, and identity. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, Inc.

Hills, M. (2002). Fan cultures. London, UK: Routledge.

Ives, N. (2010, April 5). Publishers experiment with iPad ad models. Advertising Age, 81(14), 2-17.

Jaroslovsky, R. (2010, February 4). An iPad in your pad? It’s up to the Apps.

Jenkins, H. (1992). Textual poachers: Television fans and participatory culture. New York, NY: Routledge.

Klaassen, A., & Lakin, M.. (2008, July). We get it: The iPhone’s big. App Store will make it bigger. Advertising Age, 79(27), 3,24.

Kuehlein, J. P. (2010, April 4). iPad to let comics turn page? Graphic stories haven’t been altered by digital culture so far. That may be about to change.

Lopes, P. (2006, September). Culture and stigma: Popular culture and the case of comic books. Sociological Forum, 27(3), 387-414.

Lowe, S. (2010, April 7). How the iPad can change the comics industry: The tech perspective.

McAllister, M. (2001). Ownership concentration in the U.S. comic book industry. In M. P. McAllister, E. H. Sewell Jr., and I. Gordan (Eds.) Comics and Ideology, pp. 15-38. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

MacDonald, H. (2007, February 23). Graphic novel sales hit $330 million in 2006.

Mackay, B. (2007, March 18). Hero deficit: Comic books in decline. The Toronto Star.

MacMillan, D. (2010, April 5). Comic book publishers plot comeback via Apple iPad.

Martinelli, N. (2010, February 3). Holy heart failure! Comics await the iPad.

Masters, C. (2006, August 10). America is drawn to manga. Time.

McClellan, R. (2010, March 16). iPad, EPUB, Apps, and comics – Oh, my!

Meadows, C. (2010, April 12). Will the iPad save comics, destroy comic book shops, or increase comic book piracy?

Melrose, K. (2010, March 29). Superman back on top as Action Comics #1 sells for record $1.5 million.

(2010, March). Mobile apps on rise. Health Management Technology, 31(3), 8.

Morrissey, B. (2010, April 5). iPad changes everything?. Adweek, 51(14), 6.

Nyberg, A. K. (1998). Seal of approval: The history of the Comics Code. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

(2009, September 9). Paul Levitz no longer Publisher and President of DC Comics [Press release].

Patel, K. (2010, March 22). Little love for the mobile web in app-adoring world.

Phegley, K. (2009, December 31). Marvel and Disney: A done deal.

Phegley, K. (2010, January 27). The iPad and comics: What’s next?

Reid, C., & Milliot, J. (2010, February 1). Apple’s iPad invades Digital Book World. Publishers Weekly, 257(5), 4-5.

Sadighi, L. (2010, January 27). Apple’s iPad: Kindle killer?

Schiller, K. (2010, April 8). iPad already impacting.

Snell, J. (2010, January 28). iPad: Perfect for digital comics?

Solomon, M. R., Zaichkowsky, J. L., and Polegato, R. (2008). Consumer behaviour: Buying, having, and being (Custom edition for Ryerson University). Toronto, ON: Pearson Custom Publishing.

St. Louis, H. (2009, October 28). iPhone apps for comics are stupid.

St. Louis, H. (2009, October 31). Web comics: Rumoured Apple iTablet is second coming for comic book industry.

Thornton, S. (1996). Club cultures: Music, media, and subcultural capital. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Thorpe, V. (2009, March 22). Why women read more than men. The Observer.

Warren, K. (2010, January 28). The Apple iPad, comics, and you.

Witek, J. (1999). Comic books as history: The narrative art of Jack Johnson, Art Spiegelmen, and Harvey Pekar. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Wright, B. W. (2001). Comic book nation: The transformation of youth culture in America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Shelley Smarz is a comic book and business scholar. When she’s not discussing the behaviour of consumers of comic books, you can find her enjoying a cuppa hot tea. As much as she wishes that she could say that she takes it “as it comes”, she actually takes it with a splash of cream and two sugars.