It’s one of those weeks. Three assignments due in seven days and I have a cold. But it’s not one of those awesome colds where you’re so sick you can’t get out of bed. It’s one of those colds where I can function (even though I have enough cold meds flowing through my veins to make me legally inebriated) but it’s only at 30%. The Head of my Department paid me the ultimate in complements when he said that “You at 30%, is like other people at 60%. So, don’t worry about getting back up to 100%, all you need is 50%.” (You know, businessmen and their numbers.) Still, I dread the feedback I’m going to get on the preliminary literature review since I wrote it while hallucinating zombie unicorns eating the brains of a pantsless hobo.

It’s a beautiful evening. I’m down in the city (where I go to school). And it’s late. Softly raining. Warm enough (finally) that I don’t really need a coat. I love the city on nights like this. It’s almost too quiet. Until the silence and serenity is shattered when a drunken hobo drops his pants and shouts.

So, until I get a cache of articles under my belt for this specific eventuality (when a column is due and I’m too busy to write a new one), I’ve decided to modify (read: heavily edit) and serialize parts of my MA in Popular Culture’s major research paper (MRP). So, ladies and gentlemen, without further ado, I give you part one of the MRP of DOOM!

I haven’t managed to put together a references/bibliography page yet. I’ll get on that as soon as I can and there will be a standing page of everything I referenced/used/read for those of you who happen to be engaging in some comic book scholarship.

Just think. Once this MRP has been serialized and once I’m finished researching and writing my MBA MRP (how to get more chicks reading superhero comic books), I’ll probably cut that up and post it. Hey, at least I recycle.

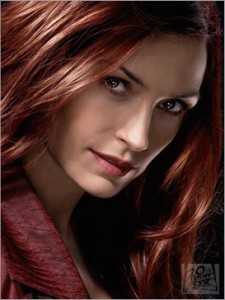

“With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility, But Absolute Power Corrupts Absolutely” A Feminist Analysis of Jean Grey/Phoenix/Dark Phoenix in Comics and Film. (A MRP in many Parts)

“We’ve always been ready for female superheroes. Because women want to be them and men want to do them.” – Famke Janssen (Jean Grey/Phoenix in the X-Men film franchise)

Texts that are created and disseminated by popular culture industries – like comic books, videogames, television, and film – are communicate the values and mores of the culture that produced them. Fingeroth argues, “Popular culture is by definition made up of the stories and myths with which most people in a society are familiar. In the sense that every piece of fiction has an agenda – even if that agenda is that the status quo is good – then every piece of fiction has a propaganda element” (94). In other words, popular culture texts have a transmissive function. Whether these texts reproduce the dominant ideology or whether the cultural hegemony is challenged by them is determined both by the producers and consumers of culture. Regardless of its position to the dominant ideology, popular culture texts – such as the ones discussed in this paper – have a profound influence on society.

According to Will Eisner, both film and comic books are graphic narratives. That is, they are a form of “narration that employs image to transmit an idea” (Graphic 6). Superhero comics, much like big budget action films, are usually dismissed as a symbol of masculinist youth and entertainment culture; seen as having very little cultural value and have, until recently, received very little scholarly attention (though action films have received more attention from scholars than comic books have). However, the purpose of comic books is not just entertainment. Rather, they serve as a mythological repository through which ideology is reproduced and naturalized. Tasker connects the larger-than-life body types that are found in big-budget action films as symbolic, referring to shared cultural tales found in myth and fantasy. Further, she notes that these symbols – especially when you look at film adaptations of comic book narratives such as Conan (John Milius, 1982) and Red Sonja (Richard Fleischer, 1985) – are also closely related their comic book progenitors: “Accompanying boldly drawn physical characteristics of the heroes and heroines are clear judgements between good and evil – there are few moral grey areas” (Tasker, Spectacular 28). Expanding this to the comic book origins of these action characters, you see similar differentiations between good and evil. As a result, mainstream comics are morality plays. They offer no place for ambiguity or negotiation, especially in the early days of the medium, simply reflecting how things should be rather than how things are.

However, in the 1960s, Marvel Comics, challenged the black and white morality of earlier comics by introducing ambiguity and spaces of negotiation within the text to create a more realistic narrative world. The idealized, higher morals of the superhero were revealed for the fiction that they are. Marvel superheroes, rather being paragons of virtue, were human beings who often battled with the powers that were bestowed upon them. Marvel created rich narrative worlds where fallible superheroes sought to reject their powers and where socio-political changes in society were reflected in the comic book narratives. For example, in the earliest Amazing Spider-Man stories Peter Parker often struggles with his role as a superhero and contemplates retirement a number of times (the earliest of which occurs in Amazing Spider-Man #3 (July 1963)). Furthermore, by adding increasing layers of complexity and social commentary onto the comic book narratives, Marvel was able to maintain their readership well into adulthood.

Just as superheroes changed, so too did the filmic representations of women, especially in the last forty years. In early feminist film analyses, scholars identified women’s role in film to be an object of desire, “as (passive) raw material for the (active) gaze of man” (Mulvey, Visual 493). Overall, cinematic representations have improved, due to the influence of second wave feminism and the powerful “action babe heroines” from movies in the late 1970s and the early 1980s. Examples from film include both Sarah Connor (The Terminator series of films (James Cameron, 1984)) and Ripley (Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979); Aliens (James Cameron, 1986)). These filmic action heroines soon transitioned onto the smaller television screen in the characters of Buffy (1997), Xena (1995), and Nikita (1997) (O’Day 208). However, these representations are often contradictory as they:

depict women as strong, independent, and capable fighters, [but] they continue to embed such images of women within a context that defines femininity in terms of physical beauty and sexual attractiveness to men, and [narratives] that draws on traditional misogynist stereotypes that reduce femininity to a figure of “fascinating and threatening alterity.” (Arons 27)

In other words, despite these examples of powerful heroines in film, the majority of powerful women in films are reduced to nothing more than a pretty face and a sexually available body. In short, these women represent the dangerous other who must be contained at all costs, lest she threaten men’s gendered power positions in society.

Ultimately, the role of feminist film theorists is the same as the one that Lillian Robinson explicitly states is the aim of feminist comic book scholarship is to create “an understanding of how the representation of an icon derives from and serves as well as challenges – the dominant social forces” in society (6). Therefore, as popular culture texts, comic books are contradictory: they are both in service of and a challenge to hegemonic social forces. One of the central figures that explicate these contradictions is the female superhero whose role in comic books has been ambiguous since it medium’s inceptions. On the one hand, the superheroine is celebrated as a feminist icon. In this instance, comic books provide a place where gendered power relations can be negotiated both inside and outside of the narrative. On the other hand, comic books have a long history of victimizing its superheroines, usually in the most vicious and violent ways possible and only if it propels a male superhero to take action in response. I argue that the truth lies somewhere in between the two.

Ultimately, the role of feminist film theorists is the same as the one that Lillian Robinson explicitly states is the aim of feminist comic book scholarship is to create “an understanding of how the representation of an icon derives from and serves as well as challenges – the dominant social forces” in society (6). Therefore, as popular culture texts, comic books are contradictory: they are both in service of and a challenge to hegemonic social forces. One of the central figures that explicate these contradictions is the female superhero whose role in comic books has been ambiguous since it medium’s inceptions. On the one hand, the superheroine is celebrated as a feminist icon. In this instance, comic books provide a place where gendered power relations can be negotiated both inside and outside of the narrative. On the other hand, comic books have a long history of victimizing its superheroines, usually in the most vicious and violent ways possible and only if it propels a male superhero to take action in response. I argue that the truth lies somewhere in between the two.

Reflecting gains made through the feminist movement, Marvel Comics superheroines underwent drastic changes in the 1970s, and the women of The X-Men – or X-Women – were no different. Both the number of female characters and their power levels both increased. However, as with other female comic book characters during this time, the images of these women in comics were contradictory and have, to a large extent, remained contradictory. These superheroes were powerful women but this power was also often negated through a number of narrative and structural mechanisms within the stories – such as portraying them as hypersexualized objects of desire, infantilizing them, or relegating them to smaller support roles. However, looking closely at the X-Women, specifically, these characters fared better in terms of how they were represented than other women in comic books. By no means am I suggesting that The X-Men comic books are free of sexism (or any other –ism, for that matter) and it would be naïve to assume that “all representations of superheroes promote the equal-opportunity perspective on heroism” (O’Reilly 273). As long-time comic book fan, I believe that there are a number of comic book storylines that are not just sexist but come very close to being outright misogynist. For example, when Alan Moore was writing Batman: The Killing Joke (1988), a one-shot issue where Barbara Gordon – who was also currently Batgirl – was shot (and paralyzed) by the Joker. The Joker then takes photographs of her, in various states of undress, writhing in pain in an attempt to drive her father, Commissioner Jim Gordon, insane. (The Joker’s running theory was that all that stood between a good man and insanity was a single bad day). The narrative ends with Gordon rescued, his daughter paralyzed from the waist down, and the Batman and the Joker sharing a joke.

When Moore phoned his editor, Len Wein, to ask for permission to cripple the current Batgirl, Wein went to check with Dick Giordano, who was DC Comics Executive Editorial Director at the time. Moore was put on hold and then “Len [Wein] got back onto the phone and said, ‘Yeah, okay, cripple the bitch’” (Moore, qtd. in Cochran).

However, it is not just the female X-Men who are literally and figuratively othered within the narrative discourse. Both the men and women of the X-Men are others in that they are mutants. In both the films and the comic books, most mutants are physically similar to humans – the difference between the two is that mutants carry an extra gene, the X-Gene, which is responsible for their mutation. Within the X-Men universe, those mutants who are physically indistinguishable from humans can pass as human and are, thus, symbolically or figuratively othered. Those mutants who cannot pass as human, on the other hand, are literally othered – and can experience discrimination. By doubly othering these female superheroes, the authors can not only engage in gendered play but also provide a space in which to interrogate and deconstruct gender issues and the politics of representation. This negates the dangers to male subjectivity. This connects back to comics’ mythological or folkloric function, the medium “takes on a psychoanalytic quality . . . project[ing] our fears and anxieties” and negotiating with them in order to negate their threat to the construction of the self. (Otero 284).

My aim in this analysis is to investigate the divergent ways in which a powerful female character is portrayed in both the comic book source material and in the film adaptation. Specifically, I examined the representations of Jean Grey/Marvel Girl/Phoenix/Dark Phoenix in The X-Men comic books from her first appearance in X-Men #1 (Lee and Kirby, September 1963) to the end of The Dark Phoenix Saga (Claremont and Bryne, September 1980). I then examined the cinematic adaptations of Jean Grey/Phoenix in all three of the X-Men (Bryan Singer, 2000; Bryan Singer 2003; Brett Ratner, 2006) movies in order to see how the narratives overlapped and what was omitted or changed during the adaptation process. The final analysis that is contained within this paper, however, focuses only on The Dark Phoenix Saga – Uncanny X-Men #129-137 (Claremont and Bryne, January 1980 – September 1980) – and X-Men 3: The Last Stand (Brett Ratner, 2006). I have included relevant information about each character’s background in order to contextualize my analysis within the larger intertextual framework through which comic readers construct meaning. This analysis will demonstrate that the 1980s comic book source text offers a more positive representation of Jean’s character than does the 2006 film adaptation.

Shelley Smarz is a life long comic book fan. She’s currently attending the presdigious Ryerson University and has a TPB of Birds of Prey (Perfect Pitch) on her bedside table. She’s now at 40% and has stopped the cold meds that make her hallucinate evil zombie clowns eating the brains of the zombie unicorns.