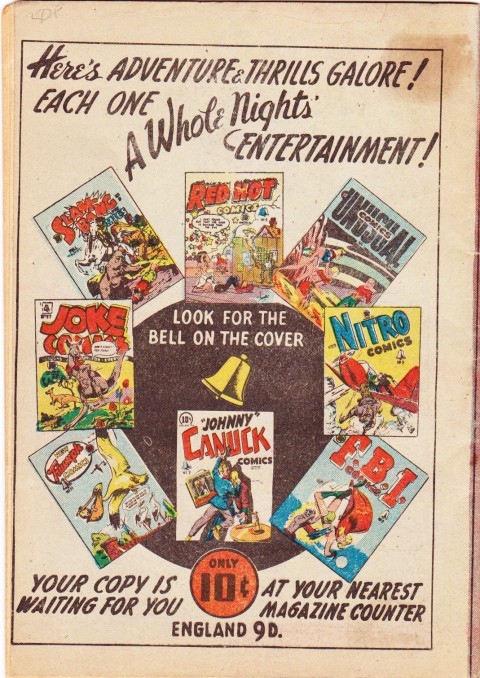

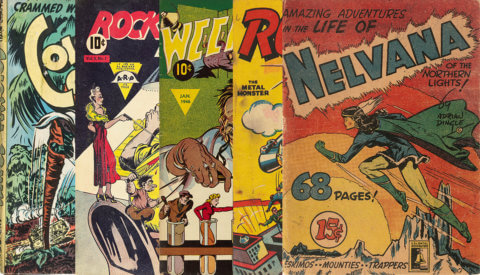

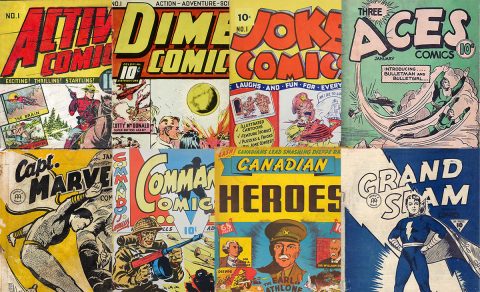

The good discussion generated by my last post needs to be seen through little. Besides, I had a busy week and have nothing up my sleeve for this week’s post. The comics in the main graphic all came out in 1946, the last WECA year, and almost all of them had American reprinted guts with most covers being re-treads from older original bell comics and a large percentage of the final product was intended for the UK market as you can see in the price indicator at the bottom. Are these books Canadian and are they less Canadian than the original WECA black-and-white books?

In last week’s post we brought up some of the important criteria for determining whether or not we could call a comic book our own (that is Canadian). Let me try to summarize the ones that come to mind in a list:

- The comic is published and printed by a Canadian company in Canada.

- The comic is assembled (writer, penciller, inker…) with a majority of creators who can justifiably be called Canadian at the time the book came out.

- The comic contains a main character that is identified as Canadian.

- The comic came about as a result of or response to a Canadian historical, cultural, or political event.

- The comic reaches out to a Canadian audience through letter pages, contests, and Canadian advertising.

That’s all I can come up with at the moment, maybe there are some others as well.

My question is this: how would you rank these in order of importance, and which of these are indispensable and which are of lesser importance?

Is a comic that has all of these criteria “more Canadian” than a comic that has just one? Can comics have a degree of “Canadian-ness?” If we can call an issue of Wolverine Canadian because the main character has revealed Canadian origins, is the book less Canadian than a Fuddle-Duddle comic or a WECA book?

I am very curious to see what thoughts everybody can share on this and it will give us some ammunition and anticipated direction for our panel at Niagara Con in a month.

I’d go with the following by importance:

#2 – created by Canadians

#1 – published by Canadians

And then completely discount the rest (3, 4, 5, 6) as not being Canadian unless they were either created by (#2) or published by (#1) Canadians.

For example, in my mind, (#3) an American publisher’s comic featuring a Canadian by American creators is still an American comic. (#4) An American publisher’s comic about a Canadian event by American creators is still an American comic. (#5) An American publisher’s comic by American creators that reaches out to Canadians to participate, advertise or promote to is still an American comic.

I’m with Kevin. #2 is the only one that’s crucial to the definition of Canadianness; #1 is a nice-to-have, but not essential. The rest are beside the point, though it’s worth examining the use of Canadian characters, the literary treatment of our history and how books are marketed to Canadian audiences; those things aren’t helpful in defining what Canadian content is, but they illustrate the world in which it exists.

“Degrees of Canadianness” is a risky path to go down, especially when it comes to the content of the work, because then you get bogged down in questions of which stories are or aren’t Canadian. Canada Reads had this problem two years ago in picking Carmen Aguirre’s Something Fierce; the author is a Canadian citizen, sure, but it’s a book about her experiences in Bolivia and Chile, and the judges dwelt a little too long on questions of whether it was Canadian “enough” to merit winning. Some of the judges argued, rightly I think, that immigrant and exilic narratives are so important to what makes Canada what it is that Aguirre’s story counts as a Canadian story, or at least Canadian “enough.”

Another example, this time from comics: Anthony Woodward’s This Town, which is a journal comic about how the author and his wife decided to pack up their life in Ballarat, Australia, and move to Winnipeg. The book ends with the Woodwards getting their visas, so it was published (in Australia, by Sure Shot Comics) after they became Canadians, but written before. Is it a Canadian comic? I’d say so, but it’s equally an Australian comic. More interestingly: would it still be a Canadian comic if they didn’t get the visas and went back to Australia?

Great comments and ideas Kevin and Evan. Using only #2 and dropping the rest we would have to consider Todd McFarlane’s Spawn for Image Comics a Canadian comic and those Bell Features titles in the graphic at the top of the page could not be considered Canadian comics.

If I posit the problem of choosing the best “Canadian” comic of the year I guess I would be using different criteria for the qualifier than I would be if I said, “I collect Canadian comics.” I know collectors (as probably you do as well) who collect both the American originals for Dell titles such as Tarzan, Roy Rogers, Gene Autrey, etc. along with the Canadian versions published at the same time. As you know, some collectors specialize in Canadian price variants and say that they collect Canadian comics. I like to pick up Canadian hybrids, repacks and reprints from that post-WECA period 1947 to 1953 and like to say that I collect these Canadian comics. Where does all this kind of stuff take us?

I don’t consider those to be Canadian comics, but rather Canadian Variants. Something repackaged or labelled slightly different from their American counterparts for sale in our neck of the woods. To me the term “Canadian comics” = comics by Canadians.

I like number 5. I really like number 5 but with an adjustment: I think if the message of the comic (or any other medium) was created with the intention of reaching out to it’s audience familiar with and can appreciate the unique themes, tropes, values and mores that a Canadian can identify with and appreciate, then it is Canadian.

But this presents another problem. In order to ask, ‘What is a Canadian Comic?” we have to be able to answer the question, “What does it mean to be a Canadian”.

I can’t answer that.

I know a lot of people who can’t. Can you? I have a hard time thinking of unique values and themes that help define who we are as a people. A part of me thinks that’s why we have such a difficult time identifying what it means to be Canadian without resorting to saying, ‘beer and hockey’. They’re the most familiar symbols that we identify with and why people get defensive when they’re critiqued and I think it’s because we have so few of them. (Funny scene in a bad movie, Canadian Bacon. John Candy plays an American who’s in Canada watching a hockey game at an arena with friends. They’re both complaining about how much they don’t like Canada when John Candy says, “I’ll tell you another thing, their beer sucks.” The entire arena, hockey players too, stop and just stare at John Candy. Hockey players begin jumping the glass and a fight breaks out. It made me laugh because my American cousin said that to me once and I wanted to react in the same way.)

So this brings me to my next point, can Canadian Bacon, a movie with so much Canadiana, made by an American (Michael Moore) who loves Canada and released his film in America be considered Canadian? There are tons of familiar themes and images that any Canadian would identify with and although there are lots of stereotypes, they’re not condescending but rather poke fun at the American identity by juxtaposing our cultures. This is why I would say ‘no’ to Canadian Bacon being considered Canadian. The message is meant for American consumption. (I’ll come back to this in a second but trust me I’m going somewhere with it).

Back to comics, Wolverine, with all of it’s Canadian back story and Canadian history and good intentions by Marvel for creating the character as a ‘thank-you’ for Canadian fans aside, is NOT Canadian. He is meant for American consumption. Even the whole ‘Weapon X/Super Soldier/clandestine government agency ‘ concept is distinctly American. (When was the last time you saw an American movie that didn’t glorify the military in some way). So let’s take it one step further, is Alpha Flight Canadian? They were created by a (mostly) Canadian. The comic frequently takes place in Canadian locations and even dealt with Canadian issues. Early on, I would say Alpha Flight was Canadian – but not because of where John Byrne grew up, but because issues like separatism and the FLQ would creep up from time to time and even play an important part of the story. When Byrne left Alpha Flight and Bill Mantlo took over, it ceased being a Canadian comic book because it ceased to explore unique Canadian themes on some level. For the most part, the creative team plays an important part in defining what a Canadian Comic book is, but it’s not the only part.

Spawn is NOT Canadian. Although the general themes are universal the main characters are American with American hopes and dreams, live and take place in American cities and deal with atypical American problems. Is this something that would appeal to a Canadian audience? In the broadest sense, maybe but I think that’s where it ends. Can Americans or non-Canadians create Canadian art? Sure, but often it’s about their experiences in Canada from their perspective and how it reflects on their lives and vice-verse as well.

Now let’s take an opposite look at Canadian Bacon. What if a Canadian writer and artist team created an American patriotic super hero. Would that be Canadian or American? Again, it would come down to the message presented to the target audience. What if it were an American Super soldier whose values were what Canadians stereotypically believe to be American and was used to help define who we are as a culture? I think that’s just as valid as any other piece of Canadian art (my only problem with that would be that we as Canadians tend to focus too much of our identity on who we aren’t rather than who we are). This is ultimately why I don’t agree with just the birth origin of the creative team as a definition for ‘What is a Canadian Comic Book’. There’s more to it than that. Much more.

So back to the question, ‘What does it mean to be Canadian?’ I still can’t answer that, but it’s always worth examining and I think one of the best ways is to take broad general themes and narrow and explore them through unique viewpoints. In that regards, I can’t think of a better way than through comics. I really do believe that. I think the best is yet to come for Canadian comics and I think a better question for creators and fans to ask would be, ‘What Can Comics Tell Me About What it Means to be A Canadian.”

Walking around TCAF yesterday and looking at the exhibits and side events, that event’s attempt to connect with consulates around the globe to bring an international flavour to the event – there are spotlights on Japanese comics, Norwegian comics, French Comics, etc. and all that did was reinforce my opinion that it’s that when you are discussing national comics, it’s their origin that is the defining factor.

When I walk into a room of displays featuring examples of work by Norwegian comics creators or look at a book entitled Norwegian Comics 2012, the defining element is that the comics are by Norwegian creators, not that they are displaying Norwegian elements. As an outsider observing those comics I might draw conclusions based on those examples about the comics creators from Norway when their work is displayed side-by-side, and you can see common elements used in their comics. I saw nothing in the examples presented that seemed distinctly Norwegian element-wise (i.e. no Norwegian equivalents to beavers, maple syrup and maple leaves). Yet I accept them to be Norwegian Comics.

Many of our problems with identifying Canadian work is that we generally work in or around the American comics industry because comics, let’s face it, are a commercial art form, although few people make a lot of money from them.

It’s our choices in how to express those universal themes within the work — they are the mirror’s reflection back on what we as Canadians feel to be important. That’s where the Canadian-ness of our morality, values, social conscience, et al. come out to play.

What’s your take on The Tabloid Press Spirit and Gamut magazine issues published by Sheridan College?

It’s worth bearing in mind that Will Eisner had some art instruction from renknowned Canadian artist/ instructor George Bridgman (whose books on drawing are still available).

jim b.

Thanks for your well-thought out and considered responses Nelson and Kevin. Maybe we’ll never come up with a final answer but it’s teaching me to listen more closely to what every body else thinks about it.

Nelson your final point about taking into account what the book itself might tell us about ourselves and what it means to be Canadian seems to me to be a valid sixth point that could be added to the list of five criteria I’ve mentioned.

When I lived in India a few decades ago, I remember that there were a few Americans in the city who told the local population that they were Canadian in order to receive a more favourable reception from that local population. Whenever I’ve lived or travelled abroad people seem to like Canadians and authorities will urge to make it known or visible that you are Canadian. The irony is that even though we ourselves can’t define our Canadian-ness, others seem to clearly perceive it and appreciate it.

Also, In order to qualify for the Giller Book Prize for example the entry must be written by a Canadian citizen or permanent resident AND the book must be published in Canada. To me this is a set of criteria that is analogous to those that would define what qualifies to be called a Canadian comic. The comic must be created by Canadians AND it must be published in Canada. Spawn, for example, was created by a Canadian but not published in Canada and so is not a Canadian comic. This is a case where publication takes priority over creation in defining Canadian-ness.

For me both initial criteria are fundamental to saying whether or not a comic is truly Canadian. It must be published in Canada AND its creators must be Canadian. Canadian editions of American comics, such as the Dell reprints and the Superior Publications comics whose creators were from American studios are partly Canadian (and collectors treasure them as such).

The “Canadian” in the Joe Shuster Canadian Comic Book Hall of Fame seems to stand for the fact that the creator whom the award is named after or the inductee is Canadian, not necessarily that they ever produced a Canadian comic book. To my knowledge, Hal Foster, Win Mortimer, Todd McFarlane and even Joe Shuster himself never produced a “Canadian” comic book and they are all in the Hall of Fame.

The question of defining what a Canadian comic book is or what makes a comic book Canadian can take on strange spirals. I’m happy that it has some traction because I’m very curious about it and all the responses so far have helped make what is involved in this designation a little clearer.

HI Jim, nice to hear from you with your always informative responses. I own a copy of this Eisner book that came out of Sheridan and it occupies a proud place in the Canadian section of my collection even though its creator was not a Canadian. I believe its content is unique to this publication and was never intended to appear outside of Canada.

It’s one of my prized books as well Ivan. I can only imagine what actually being in the cartooning class for this would have been like.

Wow, this must be one of the few posts with a number of the responses that are longer than the original post itself??!!

I’d accept that a 100% Canadian comic book has to have all of the elements originate in Canada.

However, the nature of the funnybook and strip cartooning business (WECA era excluded) up until about 1970 was that if you wanted to be a successful cartoonist you had to move somewhere near the syndicates, which were based in the US. There are exceptions – the wonderful Jimmy Frise from Port Perry, ON for example, with his Birdseye Central and Juniper Junction strips produced for the Toronto Star.

Shuster aside, who moved to Cleveland with his family, Foster, Mortimer, Byrne and even Albert Chartier and Gene Day for a time, all ended up in or within commuting distance to NYC or Chicago because that’s where the work was being assigned and the comics produced — and in those days we didn’t have FedEx or the internet to send speedy delivery of the work to the publisher so you needed to be nearby. Todd’s a case of someone who was in the US for school (on a baseball scholarship) and married an American, so he stayed in the US as he made the shift from baseball to cartooning.

Anyway, the Shusters are “the Canadian Comic Book Creator Awards” and not the “Canadian Comic Book Awards” for that very specific reason — we felt that we should recognize the many people who are Canadian working in comics (at home and abroad) and that a Giller Prize 100% Canadian model did not work for Canada since so many of our talented folks end up having their work published by American and European publishers.