Many of us ‘oldsters’ got punted into the world of Canadian war time comic books by Patrick Loubert and Michael Hirsh’s 1971 book, The Great Canadian Comic Books. Clive Smith was the British ex-pat behind the design and assembly of that book. It was a wonderful opportunity to have a chance to speak with Clive Smith about his background and career. This snaps another piece in place in the great jig-saw puzzle of our Canadian comic books.

With Michael Hirsh and Patrick Loubert, Clive Smith went on to found Nelvana, Canada’s first and largest animation company. In fact, Nelvana became the largest independent animation company in the world. Through Nelvana, Clive Smith produced and directed hundreds of projects including Rock & Rule, Devil and Daniel Mouse, and the first two Star Wars cartoon series: Star Wars: Droids and Star Wars: Ewoks in 1985-86 not to mention animated TV series such as Babar, Tin Tin, Rupert, and Beetlejuice.

Clive Smith Interview by Ivan Kocmarek, Feb. 21, 2018

IK: Thanks for giving me a chance to speak with you, Clive. Can you start right at the beginning.

CS: I was born in Edgeware, which is north of London, but I grew up in Willesden, which is in northwest London. What happened was that my mother won the football pools in 1952, I believe. She won £808 which is probably the equivalent of a couple of hundred thousand Canadian dollars today—enough to change your life drastically, especially just after the war. I mean, you know what London was like after the war. It was pretty desolate… horrible, dirty… and dangerous.

Her winning the pools coincided with other members of the family moving to Africa. Those members of the family lived in the family house in Ealing, which is in west London and, after they moved to Africa, we took over their flat in the family house. My mother had 14 brothers and sisters and the family house was owned by one of my mother’s sisters. Some of them didn’t make it through the war, but I grew up with a lot of aunts and uncles. It was a big, big family. So, when we moved into this house, we moved in with two aunts and an uncle. It also had a massive garden, which was very cool. That’s where I had my formative years. The Willesden years were formative as well, but I am thinking of from when we moved to the Ealing house, which would have been when I was eight or nine, till I was 17 when I moved off with my girlfriend to live in The Angel, Islington on Liverpool Road and went to art school. I went to Ealing Art School for five years doing fine art, fine art printing, kinetic art… a whole bunch of things… and music, of course, because everybody who goes to art school also plays rock and roll or jazz.

IK: Now I know you play the piano. Did you get formal training or just pick it up by ear?

CS: The piano thing was interesting, because when I was very, very young, my mother’s parents lived outside of London in Welling, which then was totally country—now it’s a built-up suburb of London. They lived in this farm house and reared chickens and turkeys, and there was this little outdoor building and in it were steps going up to this room, and in this room was a piano. Whenever we visited, I would always find myself in this room bashing away on the piano. When we moved to Ealing, to the family house, guess what was in one of the rooms, that very same piano—so I continued my bashing. I loved it and I begged my parents for lessons, but they said they couldn’t possibly afford it. But the piano was so old and beat up that it probably sounded awful to anybody but me, and I think that’s what maybe prompted two things, it prompted my father to say—‘Alright, you can have piano lessons, if you promise that you will practise and that you will take it seriously because it’s two shillings a lesson and we really can’t afford that.’ I said that I’d promise to take it seriously and practise and then I started piano lessons. Soon after that, the old, beat-up piano disappeared an a newer, used piano, that my parents bought on the instalment plan, appeared. That was when I was around nine, but I stuck the lessons out till I went to art school and it was at art school that I met people who could play other instruments and we could play the same tunes together. It was quite a revelation. That set me off on a course of playing in bands. So the whole five years of art school I played with different bands. Pete Townsend was in my same art school. So many musicians had the start at art school.

IK: I remember that you did an number of gigs with the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band

CS: Roger Spear of Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band was in art school with me and we formed a quite a few early bands. We played a lot together. When the Bonzos did a reunion gig in London about ten years ago, Melleny [Clive’s wife, actress and singer Melleny Melody] and I were on stage doing some of the background stuff. It was hilarious. What happened was that I called up Roger and said, “Roger, Roger, I’ve got to get out to this!” He told me that there were no tickets left. I was disappointed, but he called me back about an hour later and said, “I’ve got a better idea. If you come backstage, I’ve got a couple of things that you have to do. There’s ‘the Rawlinsons on trombone’ [from the Bonzo’s “Intro/Outro”]. One of the instruments that Roger has is a leg with a theremin in it and on stage he strokes the leg to play it. He wanted Melleny to hold the leg out while he played it. There were a couple of other things we had to do, like wheel a dead body out and tip it over… it was hilarious. It was in one of the big theatres in the West End and it was a lot of fun.

IK: Those three things—music, art, and just performing—have always been a huge, huge part of your life.

CS: Yeah, yeah!

IK: You also worked in England on the 1965 The Beatles cartoon show.

CS: I was at loose ends and I needed a proper job because all I was doing was playing piano in pubs and painting designs on boutiques. I looked in the paper and I saw this ad for an animator and, at that time, I didn’t fully comprehend what animation was. I thought it was like pixilation or stop-motion moving of little pieces of plasticine around. I went for an interview in this small boutique animation house called ‘Group 2’ in Richmond, West London. They were sub-contracting work from a larger company [TVC Animation] in South London, who was sub-contracting work from King Features in America. So I got a job with them and we were right in the trenches at the bottom of the line animating on “The Lone Ranger” cartoon series and “The Beatles” cartoon series.

That was my intro into animation. But, once those contracts expired, the place closed down because there was really no animation industry in London. There was Halas & Batchelor, TVC Animation, and, of course, Richard Williams which was probably the primo animation company to work for. I went to interview there but had nothing really to show and so I was back on the streets.

Then I got a call from somebody who had worked with me at Group 2… either he was Canadian, or he was English and had had experience in Canada… and he said that there was a company looking for animators to work on a series in Toronto. He asked if I was interested and I said, “Absolutely not! Why would I be? Why would I leave London for—where did you say… Toronto?” It took a few more phone calls to convince me to at least have a few drinks at talk about it. It turns out this guy was Vladimir Goetzeleman who was Al Guest’s sort of Art Director or Creative Director for the company. We ended up drinking beers all afternoon and having quite an interesting conversation. I left that meeting thinking how easy it would be just to say no and carry on doing nothing really. I was very excited about animation, but I’d only worked in animation for less than two years because the work ended and the company had dissolved. Animation was all hand-drawn, hand-inked, and painted… everything was very mechanical and photographic in those days. It was the painting, and the colour, and the plastic that was sooo cool and I agreed to try out Toronto for one year. I had a return ticket and a hotel for as long as I needed it and a salary I couldn’t even believe. I had been making £4 a week and this would pay me $150 a week which, at that time, would have been the equivalent of £70 a week. I thought for one year, what is there to lose. You go to a new place, do what you want to do, and get some more experience.

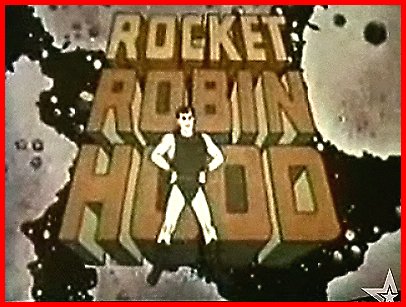

But, before the series (this was “Rocket Robin Hood”) actually got underway, Vlad got in contact with me and asked if I could come right away because there was this commercial that needed editing. So I dropped everything. I gave my animation disk to somebody to look after for a year… my piano, my books, my records I gave to people to look after for a year with the full intention of coming back. Well, the year went by in about 15 minutes. Toronto was a new place with big American cars and new things to see and do. I essentially became my own director, and this was a new experience. The limited amount of animation experience I had in England was working for a subcontractor and everything was formulaic and set out already and really just filling things in. But here, I was thrown in the deep end. That’s how it sort of all really started.

“Rocket Robin Hood” didn’t last that long. Its budget was limited, and the American funders weren’t happy with the result, so Al Guest went under. However, I was also working under Vlad in the commercials division and we had a lot of work and carried on. So, this three-storey building that was buzzing with 150 animators from all over the world all of a sudden is empty except for one half a floor and this was where the commercial people were working which were myself and about a dozen others. So we carried on until we finished our contracts and then Vlad started up a new company called Cinera and invited myself and two or three other people who were the core of the commercial division to start Cinera with him. That went on for about two years and I left because I wanted to have more control over my life and do illustration and be my own boss.

That didn’t last that long because I ran into Patrick [Loubert] and Michael [Hirsh]. Michael contacted me to do some design work. He was really looking for somebody else we both knew, but I knew that that person had returned to England. I asked Michael what he needed that person for and he told me that he had a few designs he needed. I told him that I could easily do that and that’s how we connected.

IK: Wasn’t there some connection with Carole Pope as well?

CS: Carole Pope worked for Al Guest as a painter. She painted cels. That’s where I met her and I actually went out with her… for quite a while. Then she and I and Kevin Staples started a band called “O” as in the novel, The Story of “O”. That went on and became Rough Trade. By that time I realized I was going along a different path and that I was committed to animation.

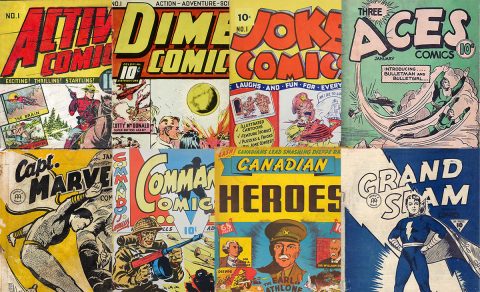

IK: Then Patrick and Michael purchase the cache of original Bell Features art pages and comic books from John Ezrin and, with your help, a book and a short documentary and a travelling art show come about—not to mention an animation company.

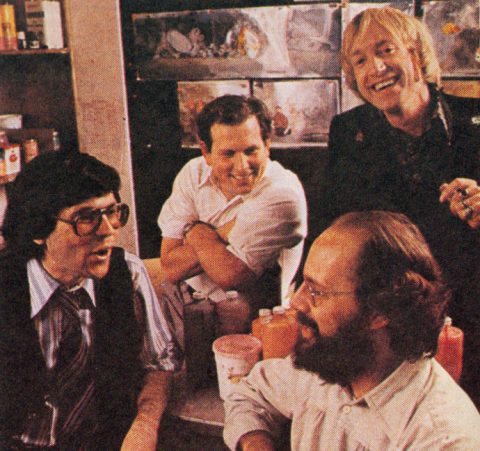

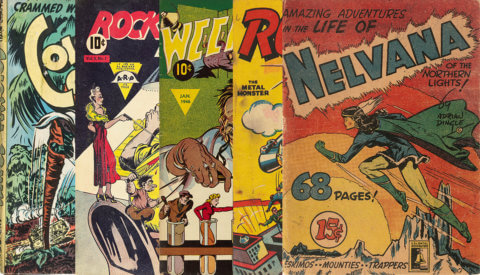

CS: Well, a lot of this stuff happened at the same time… me meeting Michael and Patrick and doing work with them and me doing other stuff on my own because I was still independent. So, they were just sort of friends and it wasn’t until we had enough common work that we were doing that we decided to form a company and to call it Nelvana. We had already bought the rights to the Bell comics and decided to call the company after one of the chief characters although an earlier choice was ‘Northern Lights’ but a jewellery company or something like that already had it and we couldn’t get it.

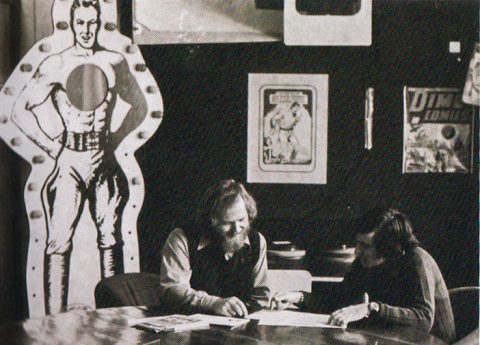

IK: What can you remember about the production The Great Canadian Comic Books?

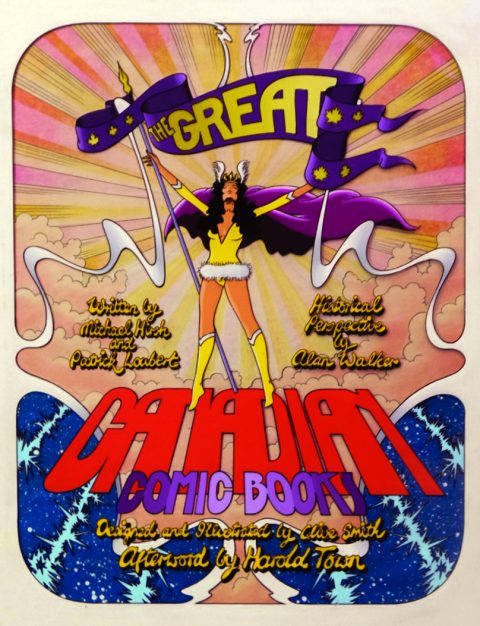

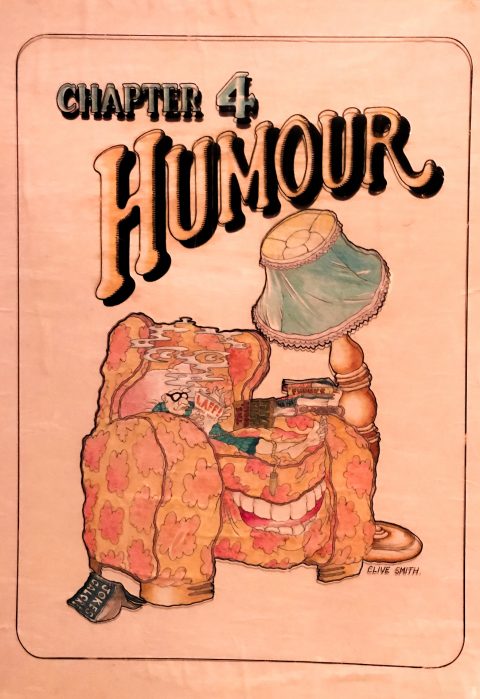

CS: We approached Peter Martin and Peter Martin being a small, local, Canadian publisher really liked the idea. Patrick and Michael wrote the copy for the book. I did illustrations for all the chapters. I remember spending hours and hours and hours at Peter Martin’s company just off Yonge and Wellesley and pasting all the pages of the book up. It wouldn’t have been done with metal type. I think it was done with a typewriter and then cut up. I would lay the cut-up chunks of copy and paste them up with pictures for every page. I remember we used wax rather than glue because I thought that was so cool. It’s a wax you put down because wax holds the piece of copy down and then they would photograph the page.

IK: You’ve got the original cover for The Great Canadian Comic Books over here on the table. It’s in remarkably good condition. Can you tell me a little about it?

CS: Yes, I can. This is actually an acetate. It’s a cel and it’s all hand drawn and hand inked. The illustration is painted on the back of a piece of acetate in the same way that we did animation cels. Then it’s layered over this background on paper which is all magic marker and coloured pencil and some paper cut-out. The title-section illustrations for the book were all don on paper. I know I have them in storage somewhere.

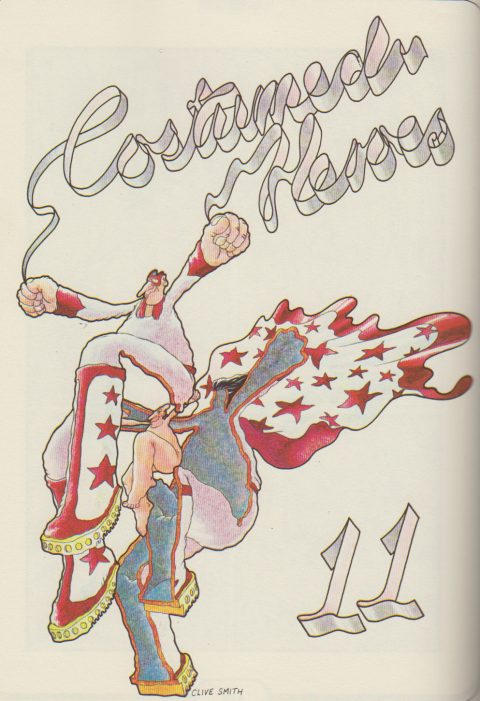

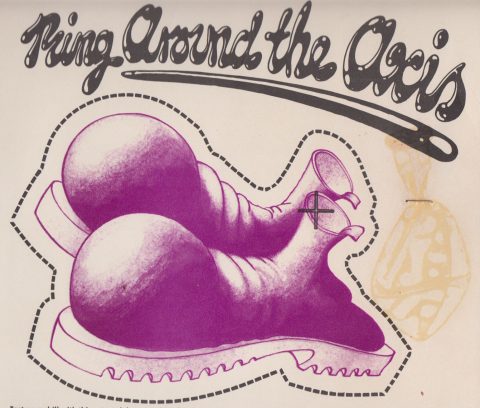

IK: What was you vision for the book. You did some wonderful illustrations for each of the sections of the book.

CS: I thought it was going to be a wonderful, coffee table book. I was very excited about it. I have to tell you, I wasn’t that very excited about the comics themselves. I thought they of really low quality.

IK: But the important thing to me was that they were Canadian. Even though part of being Canadian is faltering, but you still get it done and work on improving it.

CS: Yeah, often against all odds.

IK: Was it the original artwork you reproduced in the book or was it the actual comic book pages?

CS: I think there may have been some original art but I remember it as being mostly comic book pages.

IK: There were a couple of spin-offs from the book. The first was the Telescope documentary and then, about a year later there was the nationally travelling art show.

CS: Well, I really didn’t have much to do with the short documentary. That was all Michael and Patrick but I may have done a couple of fill-in or transition drawings. As for the art show, there were a number of framed pieces from the book and there were some original pieces that the National Gallery had loaned us.

I designed most of it and did the accompanying programme which was contained in a plastic pouch that also had a number of goodies in it such as a Speed Savage patch, a Johnny Canuck cut-out and assemble figure, and a balloon with instructions to play a game that was originally in one of the Bell comics. You would take the balloon, blow it up, paint Hitler’ face on it, cut out some oversized paper boots from the comic, paste them on the bottom of the balloon and stand it up somewhere in a corner. You’d then get some hoops, stand a little distance away, and try to toss them over the Hitler balloon ensnaring him with the hoops.

I made a giant version of this. I got a weather balloon and weather balloons you can inflate to about 10 or 12 feet in diameter. When you buy them, they’re flat and quite a small size. I had Hitler’s face printed on it and then I made up a pair of boots in paper mache. They were huge boots and I painted them black and put laces on them and everything. We would blow up the balloon and fit it to the boots and we also made a giant hoop that you could throw over the balloon and that was one of the things in the show. So, I brought this set up with me to the Kitchener-Waterloo show and, of course, when you travel with one of these balloons, you travel with it uninflated. When I got there, I’m helping set this thing up and I asked one of the supervisors at the museum if there was a garage with an air pump around and he told me that there was one about two blocks away. Now, think of this, I’m in Kitchener-Waterloo, perhaps the heaviest German population in the country. I’ve inflated this balloon with Hitler’s face on it to about 10 ft. diameter and I have to walk two blocks back in downtown Kitchener-Waterloo. I got some pretty strange looks.

I mean, we didn’t travel with the show but I volunteered to do a little introduction if the places were not too far away.

IK: It’s been over 45 years since that time what still stands out for you from that period?

CS: It was a very busy active time for the three of us and eventually for the thousand of us. We grew the company from three to over a thousand employees worldwide. The three of us started in a little third floor walk up on King Street.

I had a couple of assistants early on, but I was basically doing all the animation, painting, inking, and the shooting. I had a wind-up Bolex 16mm camera. We had two washrooms. One was used as a washroom and the other became the Camera Room. We used the toilet bowl as a light box to back-light some of the artwork. We had no money and would shoot at night because the electricity was more stable then with no industry going on. We did everything ourselves.

We had some very good friends at CBC and they would purchase fillers from us. They needed something for the spaces when a show would run short and these were called “fillers” and they were 2 or 3 min. of basically nothing. Now this was a very hard thing to do, to make short films about nothing. We also made 15 min. children’s films and the CBC would buy these for about $150 each, but for each children’s film they would buy maybe a dozen fillers and pay more altogether for the fillers than the short film. This way, we actually started to get a bit of a salary. We actually marketed them under the title Small Star Cinema. One film was called “Mr. Rubbish and the Conductor’s Guided Tour of the City.” And this came out of an incident where it was Halloween and I’d just got home from the studio, working late, and my wife at the time was all ready and dressed to go to a Halloween party and I had nothing to wear. So, I grabbed a green garbage bag and made holes in it for my head and arms, painted my face green and we were a big success at the party. That gave us the idea for the Mr. Rubbish film. Patrick was the conductor and Jock Brandis was the cameraman and we shot around town.

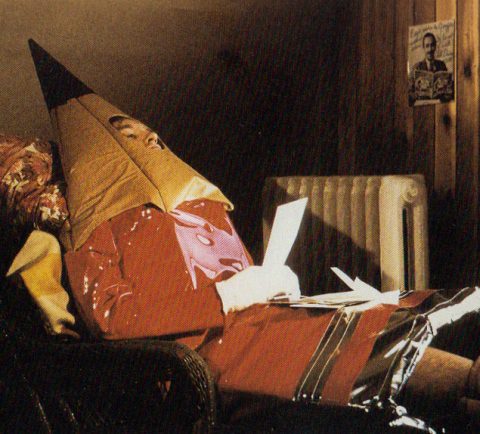

“Mr. Pencil Draws a Line” was another one. That was funny. We really didn’t have a camera crew… there were only two or three of us… and there was one long shot we needed to do where Mr. Pencil… and I was Mr. Pencil… had to run across one of those raised paths around Nathan Phillips Square. So, I’m running across that on my own in my pencil costume and the camera is on Queen St. It’s a long, big, wide shot and there’s nothing around me to show that we’re filming and this guy comes up to me and says, “Oi! Oi! Whad’ya think you’re doing? Whad’ya think you look like” and he threatens to beat me up. There must be some film of this somewhere. We had great costumes made for these films. I don’t know where they are now, but they’ve got to be somewhere.

IK: Your company now is Musta Costa Fortune. How did that come about?

CS: There was a point during the Nelvana days, before we were public, probably in the early ‘90s where it became necessary for each of us to incorporate personally. It was all to do with taxes and how the money was budgeted. Our financial advisors strongly suggested we do this. So we each (Michael, Patrick, and myself) incorporated. That’s where Ho Ho Holdings came from which is my umbrella company which owns all the other things including Musta Costa which is my production company which came about after we sold to Corus.

IK: What is something that you are working on now?

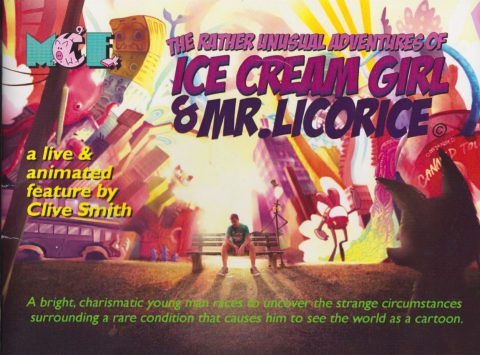

CS: I’ve been writing a script for a live action film with a lot of animation in it. It’s about a young man who has a ‘condition’ that causes him to see the world as a cartoon. It’s a bit of a metaphor for mental illness and that gives a serious thread to a film that’d very entertaining, funny, colourful, and musical. So, what this young man is struggling with could be quite funny and entertaining to us as an audience, but to him, it’s not. It’s called The Rather Unusual Adventures of Ice Cream Girl & Mr. Licorice.

I started writing it part-time about ten years ago, just putting down ideas when I got them. The seed for the idea actually came to me during that half-waking, half-sleeping state you get into at night or in the morning and I just started jotting down notes. We’re at a point now where we’re looking for funding.

IK: Clive, you’re an old school, hands on animator with flip books and hand-drawn cels. How are you responding to digital technology that is taking over animation?

CS: It’s tough. I have a hard time keeping up, quite frankly. I love it and I’m fascinated with it. There are so many new technologies developing with VR, machine intelligence, deep learning… but you’re not required to draw any more. You can sample an element or use a program to animate something or make something 3D but you still need creativity and imagination. It’s just that the tools are different.

IK: Clive, thanks for giving me this time to talk with you and allowing me to share some of your background with my readers. Thank you, along with Patrick and Michael, for contributing to our Canadian cultural identity with Nelvana Ltd., which, at the time became the largest independent animation studio in the world.

1

Fascinating…even all the non-comics diversions were fun to read. What a creative guy. Now I can look back into the Canadian Heroes book with new appreciation. Those Chapter drawings of Clive’s are classic psychedelic era artwork. Makes me think of The Yellow Submarine and the Illustrated Beatles books. Always more to learn.

Funny Bud, Clive actually worked some on The Yellow Submarine movie and you can see how those Peter Max flourishing cartoon drawings filled up our culture at the time. Oh, the Heroes of the Home Front pdf has just been completed and fine-tuned to our satisfaction. Just waiting for the cover template from the printer so that we know how wide the spine should be and then off it goes to the Orient.

Re: The Great Canadian Comic Books .This is the way i remember it anyway. There must have been some article about Canadian comic books in the newspaper because by the time the Telescope documentary aired in September i was ready with a pen and paper to write down where the book could be ordered prior to publication. My mother ordered a copy for both my brother and me (its a sibling thing) and they were delivered before Christmas . A little Johnny Canuck poster was tucked into each book along with a reverse side that had ordering info as well . When the touring exhibition made it to London my friends and i went on opening night but i don’t remember there being any supporting material aside from a really lame pamphlet on comic books in general that seems to have been prepared by some librarian at the local level.

Great to hear from you Robin. I was late to the game with The Great Canadian Comic Books and got it out of our local city library here in Hamilton in the spring of 1972. My research shows that the Telescope doc was aired on Oct. 8 in 1971 and the book came out in late November. Maybe the package wasn’t available in every one of the 13 venues it appeared at across the country in 1972-73. Hope we get a chance to sit down and talk Canadian comics sometime this year, Robin. Thanks for chiming in.

Okay. It wasn’t September that I saw the Telescope documentary on Canadian comics. It must have been October 8. Otherwise, I think I have the time line down pretty well. Not bad for 45 years later.

5