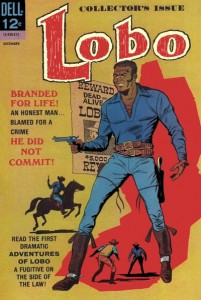

Almost 4 years ago I posted Undervalued Spotlight #44 featuring Lobo #1 published by Dell Comics in December 1965. Spotlight #44 has always been one of my favorite posts, the weight and importance of that comic had not yet translated into value and I knew it was just a matter of education.

Almost 4 years ago I posted Undervalued Spotlight #44 featuring Lobo #1 published by Dell Comics in December 1965. Spotlight #44 has always been one of my favorite posts, the weight and importance of that comic had not yet translated into value and I knew it was just a matter of education.

Back then the book carried an Overstreet Guide value of $55; today the 9.2 Overstreet value is $100, an improvement yes but still nowhere near where it should be.

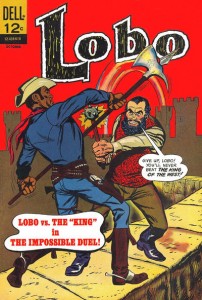

A couple of weeks ago I received and email from D.J. Arneson, yes that D.J. Arneson, editor of Dell Comics and writer of the Lobo comic. Needless to say I was thrilled. Mr. Arneson had happened upon my post in  his search for a copy of Lobo #1. I had a personal copy and was honored to send him mine. He is still looking for a copy of Lobo #2 so if anyone is sitting on a Lobo #2 please contact me, we need to get it to Mr. Arneson!

his search for a copy of Lobo #1. I had a personal copy and was honored to send him mine. He is still looking for a copy of Lobo #2 so if anyone is sitting on a Lobo #2 please contact me, we need to get it to Mr. Arneson!

This was Mr. Arneson’s email reply upon receiving the Lobo #1 in the mail:

Hi Walter,

LOBO arrived today and what a treat to read it again…after 50 years!! The first thing that struck me was how much unchanged my attitudes are insofar as justice, guns, killing and the other issues suggested in LOBO. That’s comforting.

I could not pass up an opportunity to ask Mr. Arneson a few questions: I asked him if he’d grant comicbookdaily.com an interview and he graciously agreed.

Below is part 1 of my interview with D.J. Arneson. Part 2, dealing more With Dell Comics and their 1960’s superhero line will be posted later. (Please note that I emailed Mr. Arneson the questions in advance, at a few points partial answers to the next question are found in the previous one, apologies).

——–

CBD: You created Lobo during a time of tremendous social change in the United States. Hind sight is 20/20 but in 1965 did you have a sense that a dramatic societal transformation was under way?

DJ: My perception of the underlying social foment of the time, though heartfelt and personal, was not profound. I did not read into the contemporary accounts of unrest and confrontation that surfaced, irregularly at first, in newspapers, news magazines, television and radio of cohesive forces we’d now call “movements” as in a civil rights movement or an anti-war movement, though both were underway. Though undeniably there, the unrest was too fragmented to recognize as such from my perspective.

I was certainly familiar with news accounts of lunch counter sit-ins, anti-Viet Nam demonstrations and other social issues reported in The New York Times, for example. The events were scattered both geographically and intellectually. The historical cohesion came much later when the disparate elements gathered momentum and public recognition. At the time, however, I did not perceive the bigger picture. I responded to events from a personal perspective. I believed it was wrong to go to war. I believed it was wrong to discriminate racially or any other way for that matter. But I did not identify my beliefs with larger social forces by participating in movements of any kind. I felt but did not act.

So, no, I did not foresee what history might now suggest was foreseeable.

CBD: What specific social, philosophical and/or literary influences helped you to create the character? How did he pop into your head?

DJ: One of my responsibilities as the editor of Dell Comics was to come up with new ideas for comics. Lobo was one. As I’ve described elsewhere*, my initial concept for Lobo developed from a book I’d recently read, The Negro Cowboys, by Philip Durham and Everett L. Jones, Dodd, Mead & Company, 1965. It’s still on my bookshelf.

The “pop”, if you will, was to recognize the potential for a new comic book character based on the historical record. It required more than that, of course, to capture the attention of comic book readers. Such a character would have to be bigger than life. Two classic examples came to mind; Robin Hood and The Lone Ranger. I incorporated elements of each into Lobo, who, incidentally, I originally named Black Lobo. The name was changed to simply, Lobo, by Helen Meyer, the president of Dell.

The broader implications of a black comic book character were not paramount for me in the sense that I believed Lobo would inspire social change. My intention was to create and develop a strong character. He was black because the historical basis for Lobo was derived from the Buffalo Soldiers, who were black, former Civil War soldiers stationed in the American west, who later became the “negro cowboys” of whom Lobo was one.

I was personally aware of the social circumstances of the mid-60’s as I described above and I knew a black character would get attention. But again, it was not to generate an activist social awareness but rather to create a viable comic book character who, by being black, would garner readers.

To that point I’ll add that when I was confronted by anyone who challenged what I was doing…producing comic books…as somehow irrelevant or anti-intellectual, my response and firm belief was that if reading a comic book could stimulate interest in more reading of any kind, particularly among kids who might otherwise be “non-readers”, a great good was accomplished. Much of my writing career after leaving Dell was to write books for young readers with limited reading ability or had no interest to read anything at all.

CBD: Dell publisher Helen Meyer ultimately approved the comic, this is now historically seen as a very bold and progressive move for that time. Was the matter discussed at the time in a “we must do this for society” aspect? (Note to Walter: Helen Meyer was president of Dell)

DJ: No. As I’ve indicated, even though the creation and publication of Lobo was within the social context of that time, Lobo was not a contrived effort to inspire activism of any kind. My intention was to generate an awareness in comic book readers of unfamiliar, quite interesting historical characters and events, as in, “Gee, I didn’t know that.” By inference one might imagine those readers looking for more information, but that was secondary.

CBD: Though race was an obvious topic in the comic it was not the central theme. Were the Lobo stories written to purposely stay away from the race issue?

DJ: Not at all. When you read Lobo, without reference to the illustrations, you cannot know or even figure out what his race is. There is nothing in the copy or the dialogue that identifies Lobo racially one way or the other. He was intended to be a strong character with dramatic overtones and nothing more. His race was not the issue; his historicity was.

Clearly, Lobo was black. But that was because the Buffalo Soldiers were black. He was a natural consequence of real events; a black cowboy. That’s quite different from making an historical figure black in order to make some kind of social statement. Readers could only know Lobo was black when they saw him.

Now, was it important that Lobo was black? Of course. That’s what made him so interesting. For even though he came from the same tradition that all cowboys come from, the mystique of the American west, he was different. Had he been white he’d have been just another cowboy. For young readers the blend of the familiar with the mysterious was perfect. So I thought.

There was no need to avoid the race issue because in Lobo, the issue of race was transparent. Not invisible. Transparent.

A further point regarding the ‘philosophical’ content of Lobo is that a single theme pervades the character and storyline; justice. Justice is introduced very early, developed from the mis-judgment of an incident in which Lobo, though yet unnamed, is believed to have killed someone. He hadn’t, of course, but others who came upon the scene presumed he had. It was then that he became a fugitive, wrongly accused yet determined to prove his innocence.

Now, one might read into the concept of “justice” more than criminal innocence. It could be argued that racial justice is implied. Perhaps it was. That would have been for the reader to determine and perhaps to act upon. Inasmuch as I created the character, storyline and episodes, the overarching sense of justice, both of portraying criminal and social innocence was deliberate.

CBD: Now the title was cancelled after 2 issues due to poor sales, well actually poor distribution as many sellers did not even unpack then. Was Dell aware at the time that shop owners were not putting the books out for sale? Was Dell attempting to remedy the situation somehow?

DJ: I’ve heard the assertion that Lobo failed as a consequence of distribution issues; a couple of which you mention. I do not know where that explanation for Lobo’s failure originated nor on what information it is presumably based. I have never heard, then or now, the implication that distributors returned copies of Lobo because of content, that is, that the racial implications were unacceptable.

When a projected comic book series was cancelled, the decision was solely on the basis of poor sales. I can’t presume to know why sales of a given title were poor as we did not do any sales analyses beyond what the figures, that is, how many copies of a run were sold revealed. If many, many more were returned than printed, clearly sales did not meet expectations and so further issues would not make economic sense.

CBD: I’m assuming you had more Lobo stories in the works, could you tell us if there were scripts written or art produced for later unpublished issues?

DJ: Dell’s comic book publishing timeline was quarterly. That is, titles were published on a quarterly basis; four issues a year. However, titles were not produced far in advance of quarterly publication. They were scheduled for production month by month. By produced I mean the storyline was generated, the script was written and then the illustration was done. So, even though the expectation may have been to publish the next issue of a series, the actual work on that issue was held off until the actual decision to publish was made. The decision not to publish another issue of Lobo would have been made before work on it was begun as sales figures of the preceding issue would already be available.

Unlike a television series today, we did not have X number of issues specifically planned, outlined, scripted or illustrated in advance of projected quarterly release. There was nothing “on the shelf” ready to print and distribute when the time came.

CBD: What direction were you considering taking Lobo had the series continued? Ultimately what did you want the Lobo stories to tell us?

DJ: I had no specific goals beyond what the character and storyline implied for, as I’ve described, no issues were pre-planned far in advance. Each subsequent issue would have built on the foundation established in the first two issues, though, of course, further refinements would have been normal in the development and fulfillment of those initial goals.

Thanks to Mr. Arneson for this interview.

What a great interview (so far). Thanks for this Walt! DJ Arneson is a champion and it’s great to hear that his attitude hasn’t changed much at all in the last 50 years – I certainly hope I can do the same in 50 years.

Great piece. Lobo 1 was how I found this website as well. I now proudly own two copies. Anyone interested in collecting comics for historical reasons owes it to themselves to get this issue, not just because it’s about a ‘black cowboy’ but really because it is such a fantastic read.

Hi, KiwiDan,

Thank you for your enthusiasm and kind comments. As for your attitudes, that is, beliefs, take the next 50 years in small doses, say, a year at a time. It’s OK to change your thinking…my feeling is that if core beliefs still reflect who you think you are and who you want to be, hang on to them. However, if new information and understanding open the possibility for change, go for it. There’s nothing less satisfactory, I would hold, than being the exact same person at 50 plus as one is at the start of that 50 year climb. Keep climbing.

Sincerely,

DJ Arneson

Hi, Nelson,

What a great compliment! Thanks so much. I had no thought when I wrote Lobo that it would continue to generate interest a half century later. As I told Walter, my goal was to create an authentic character that young readers at that time could recognize, perhaps not so much because he was black, but because he represented something of value in a person. I’m delighted that you see in Lobo today what I intended then.

Sincerely,

DJ Arneson

5