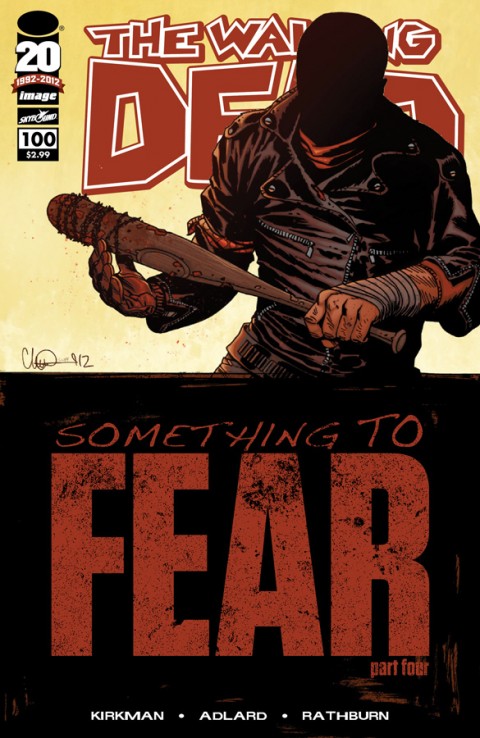

Writer/Co-Creator: Robert Kirkman

Penciller/Inker: Charlie Adlard

Grey Tones: Cliff Rathburn

Letterer: Rus Wooton

Covers: Charlie Adlard and Cliff Rathburn (A), Marc Silvestri and Sunny Gho (B), Frank Quitely (C), Todd McFarlane and John Rauch (D), Sean Phillips (E), Bryan Hitch and John Rauch (F), Ryan Ottley and John Rauch (G), Charlie Adlard and Cliff Rathburn (H), Charlie Adlard (I)

Publisher: Image Comics

When any book hits a milestone, it’s routinely momentous and deserving of a measured amount of fanfare. With its 100th issue The Walking Dead, co-created by Robert Kirkman and Tony Moore, the title hit such a milestone with its July 11th release. It was accompanied by a wealth of media hype, fan hype and more covers than can possibly be necessary. Yet in a case like this, what matters is the comic itself, as regardless, in the end, a book needs to stand on its own.

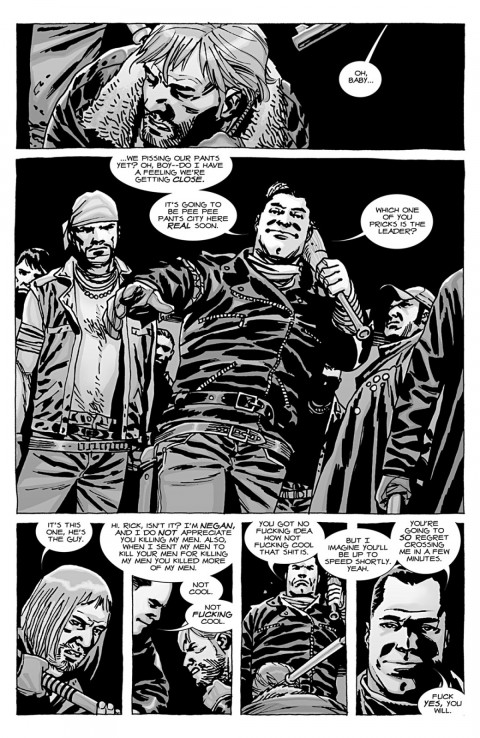

In that respect the issue played up to its strengths. This zombie-romp turned quest for survival finds humankind competing against itself for the basic means of subsistence, often engaging each other violently in order to obtain those means for survival. Such an encounter occurs in this issue where the antagonistic Negan and his band of followers attack and subdue Rick and his group, making the point repeatedly that Rick’s grip on the apex of the social hierarchy has loosened and that he –Negan– is now the alpha-figure in the zombie-killing hegemony. To emphasize this point, Kirkman’s script includes an all-too-vicious fatal beating of one of Rick’s party, a gruesome death not out of place in this setting. Considering the zeal with which Negan commits the violent act, using a baseball bat covered in barbwire, the end result is a pulped mass of what was formerly a young man’s cranium, and is arguably a step too far.

It’s clear at this point however that zombies are simply the scenery of this comic, the focus very much placed on the degenerating state of human empathy and compassion combined with the worst features of humankind and it’s self-centered fixation with the need for its own survival by any means. The title of this book becomes ironic in this respect, as the people in The Walking Dead, for all intents and purposes, are the walking dead without realizing it. Perhaps that’s the underlying conceptual beauty of the plot, with the zombies themselves functioning as little more than a mirror for humankind’s current state.

While the plot is conceptually high-handed and well thought out, the writing in the issue is poor upon Negan’s appearance through to the end. Where the opening pages are well-paced with dialogue suitable to the conversation between the characters — Rick’s defeatism, anger and apathy healthily apparent throughout — Negan’s speech is contrived, redundant and forced. Negan, who’s very much an over-bearing jerk, repeatedly emphasizes that things are changing in this landscape he now wishes to rule; a point he highlights both before and after the violent beating. The dialogue’s redundancy gives Negan a very single note personality, as though he has nothing else relevant to say or that Kirkman didn’t have enough script to fill the final pages of the issue. While the first offering works on its own, the second helping of Negan and Rick’s conversation is forced and adds nothing more than reinforcement of the principle of the societal order’s shift. This makes the final pages tedious to read, creating an underwhelming ending to what at least conceptually should have been a defining shift in the book’s direction.

Adlard’s art is a central pillar of this series, animating the horror-bound nature of Kirkman’s script with gasp-worthy, stomach churning visuals. Glenn’s death offers a particular case where the artwork works on two fronts to emphasize the reality of humankind’s capability to be innately violent towards its number, while being dually horrific for its own sake. His death plays out over several pages where his demise inches incrementally closer to reality as his friends can only watch on, while the physical toll caused by Negan and his weapon are demonstrated visually with each head-splitting crack. Accompanying Glenn’s death is an equally chilling expression of glee on Negan’s face as he horizontally swings the bat across Glenn’s face, shattering his jaw without batting a lash. The act is then finished in a series of silhouetted panels where Negan repeatedly pummels and pounds Glenn until there’s nothing left of his head but mush. As a whole, the art works well in its black and white presentation, combining with Rathburn’s greying tones to add a classic horror feel to the book. The Walking Dead wouldn’t be as appealing had it any colour, making the artwork functional for the story. Adlard provides more than these horror elements mind you; in several instances throughout he combines with Wooten to manufacture seamless reading for the eye. Early in the issue as Rick and Glenn share a conversation, Glenn’s speech carries over from one panel in which he is sitting upright to the next as he lays down in the back of the car, ending with his head resting upon the backseat. Another example of Adlard’s work is demonstrated upon the arrival of Negan’s crew when they use a snare to drag Rick from the roof of his group’s car to the ground, transitioning to two panels of Rick gasping for air and thrashing his head from side to side in an attempt to break free. His strained facial features are presented with precision with each fighting, vain attempt to breathe. It’s a continually welcome addition to the greater presentation, communicating the anger, sadness, violence, smugness and arrogance of each member of the book’s cast. Another intuitive piece of the art is Wooten’s sound effects lettering, especially during Glenn’s final moments where the lettering effects become visually less defined with each decisive, head-splattering blow, ending with a gooey mass of letters synonymous with the remnants of Glenn’s skull.

While The Walking Dead is a highly conceptual comic, illuminating humankind’s capability for violence in a survive-or-die situation, the execution of this issue is unbecoming of its reputation as an Eisner-winning series. The portrayed hegemonic shift of control from Rick to Negan is muddled and forced, dragged down by Negan’s own redundant, contradictory and profanity laden dialogue. As the central piece of the issue, it fails to hold any measure of gravity for the reader, hampered by the delivery of its own message. While pushed as a defining shift, Kirkman’s decision to re-emphasize the point drags the book down, while the repetitive dialogue during the final pages worsens the experience. This is a book that has a home in its niche, but as an introductory issue for any coming aboard amid the book and television show’s combined hype, The Walking Dead #100 does little to impress.