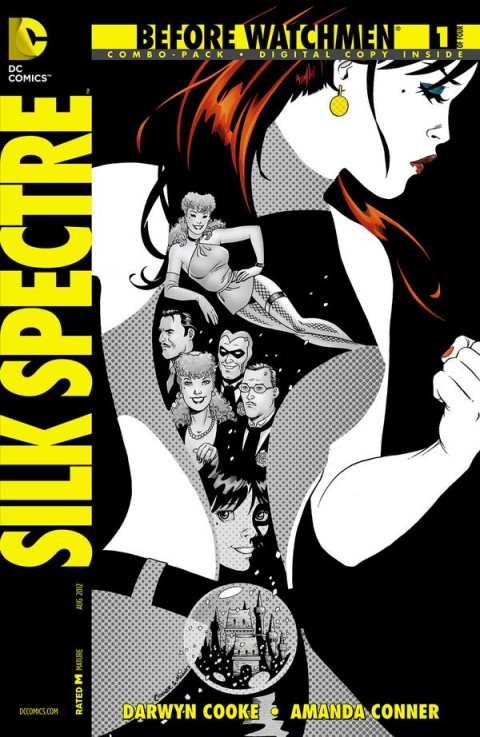

Writers: Darwyn Cooke and Amanda Conner

Artist: Amanda Conner

Colourist: Paul Mounts

Letterer: Carlos M. Mangual

Cover: Amanda Conner and Paul Mounts; Dave Johnson, Jim Lee, Scott Williams and Alex Sinclair (variants)

Publisher: DC Comics

The doomsday clock has finally struck midnight and the Watchmen prequels are finally upon us. From general observations it would seem nuclear war didn’t accompany the release of the first issue of Cooke’s Minute Men mini-series, nor has a similar catastrophic event occurred upon the release of Silk Spectre #1. Aimed to expand the past leading up to Alan Moore’s seminal Watchmen, a number of creators have thrown their names into the figurative, perhaps literal, fire of fan’s scorn upon attaching themselves to these projects, including Watchmen editor Len Wein who provides the Curse of the Crimson Corsair back-up story.

At least after two issues, the prequels are off to a solid beginning aided by Cooke’s guidance across Minute Men and Silk Spectre. While the former title focused more on the development of the team coupled with Hollis Mason’s narration and recollections about why he and his eventual teammates came to decide their calling, Silk Spectre scales the scope back exponentially and acts as a more direct tie to the original work. Laurie, the daughter of Sally Jupiter, had always alluded to the troubled relationship with her mother, especially as it relates to her deciding to become a costumed hero. The original work treated it very much in a way that paints Sally as a pushy mother who desperately wished her daughter to continue her legacy as Silk Spectre. Laurie obliged, not necessarily for any particular personal reason, rather just to please her mother. This was a theme which played out during Watchmen until their conversation at the end of the book. In this series, we find a teenage Laurie living a life as most people her age would between juggling school obligations and commitments, her love life and a vain attempt to meet the approval of her mother. Throughout the book we see flashes of Moore’s allusions, which Cooke expands and hones in on relating to the drives of both characters. It’s here we begin to understand both a little better and can find similarities between their relationship and the one between any parent and child. Where Sally imposes a set of expectations upon her daughter, we find a rebellious Laurie casting them aside despite her acceptance of the strange Batman-Robin dynamic in how Sally trains Laurie to fight.

Two thoughts come to mind upon how Cooke characterizes this relationship. Foremost it’s not a very original element to inject into the story. It’s one we could have assumed based on their previous interactions, however with its inclusion we find a mirror for our own lives which touches upon the very real, human elements of what Moore’s work accomplished. Superheroes are people in the end and subject themselves to not only public scrutiny, but they make mistakes and have expectations thrust upon them just as often as any individual would. Cooke’s execution of this aspect makes this book worthwhile as it colours a reality for all teenaged people who face expectations from their own parents. In this issue we see that relationship develop and can perhaps see a piece of the Laurie-Sally relationship in ourselves. For this book, this is its grand success, to bring us as readers into the mindset of a teenager trying to find their voice.

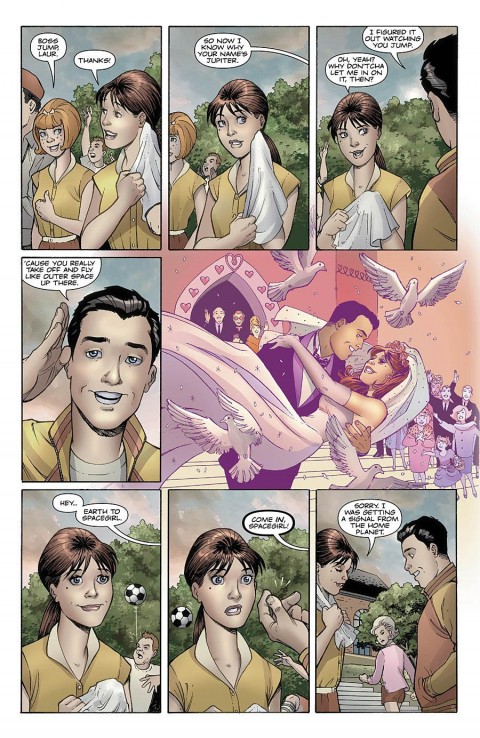

Coupled with the success of Cooke and Conner’s script is Conner’s own artwork accompanying the issue. Conner did well in capturing nuanced interactions between the characters combined with slight alterations in movement between panels. In early pages after Sally’s snow globe shatters, Conner pencils a great sequence of panels which visualizes their conversation from the perspective of the listener, off-setting these by two panels featuring both Sally and Laurie, which is later pulled back in the final panel as we see only Laurie and a teary eyed Sally sitting on their couch embracing each other. Speaking back to Laurie’s relationship to her mother, we find Conner’s talents again taking centre stage as Laurie stands next to a mirror in her room wearing her mother’s costume, almost as though she wishes to fulfill her mother’s expectations despite her obvious defiance of her legacy.

In part it’s clear she’s hesitant to embrace who her mother was and accept that reality and legacy, while also evident she has yet to grow into the person who would eventually assume the Silk Spectre mantle. The entire sequence of panels continue an earlier theme, delicately displaying shifts in the environment; Laurie moves from her room, down the stairs, into the couch and then leans to one side while reading a magazine. It all works together and tells a complete story without the need for text. The innocence and melancholy of the page is contrasted against the following page, transitioned to nicely with the inclusion of the shadowy figure in the previous page’s panel, followed by a fight between Laurie and a black-clad burglar, revealed later to be Sally. Despite their “training,” we still find the mother-daughter dynamic and inherent love that lays therein when Sally treats Laurie’s wounds. It’s touches such as this which really help push the story forward and accentuate parts of the plot that dialogue simply could not. Beyond these well detailed pages, Conner adds a touch of personal style differentiated from the rest of the art to emphasize the internal thought processes of Laurie as she reacts to moments in her life. Upon her first conversation with Greg, we see her reaction in imagining her wedding day; as her mother picks her up from school and takes her home, she imagines riding in the passenger side of her mother’s Rob Zombie Dragula styled demon car; when Greg first kisses Laurie’s bruise on her shoulder she feels as though she’s dancing among the stars; when she and Greg sit in the diner and she’s being verbally abused by Betsy, she imagines herself walking into a bottomless pit. These diversions from the main art help add an element of cartoonish humour to the story, but accurately reflects Laurie’s feelings and it works for the story being told.

This first issue was successful on most points in encouraging story development of the principal character. Where there is still murkiness regarding how the Watchmen prequels can be used to expand the message of the original work, this first issue did its job in establishing a basis for the mini-series while paying homage to the original Moore story. Between the two books released thus far, Silk Spectre is the better vehicle for that story’s communication, as Minute Men functions much in the same as Watchmen did in explaining, albeit more explicitly, the reasoning for entrance into the field of costumed-heroism. This makes it feel like more of a JSA type of story where a legacy between the two generations of crusaders is causally established. While both were solid outings, it’s difficult to forecast the success of the books nor their story’s plots, much less whether in the end these will be viewed as worthwhile contributions to the Watchmen mythology. On their own they are good comics, but the shadow of Moore’s work is ultimately going to eclipse these prequel stories regardless of their quality.

I think the biggest problem these books are going to have is in deciding whether to go out on there own and add to the original or to elaborate on the hints of the back story from the original. This one seems, in the first issue anyway to be taking the elaborate on the back story route and in the end doesn’t seem to really add anything we didn’t already know. I’m sure we all saw most of this issue in our heads while reading Watchmen the first time.

As for the art, this is surprisingly my first run in with Amanda Connors work despite her reputation and while its obviously highly skilled it comes off being a bit too cartooned compared to the source. It feels oddly out of sync with the darker, more realistic tone we’ve come to know in the Watchmen books. It’s unfortunate too since this could be an interesting book if had the freedom it needs and wasn’t tied to the Watchmen myth.

I agree with your point to a degree, but as is the case with “The Comedian,” taking liberties with the story can be equally destructive. This is really a no-win, alienating series of projects.