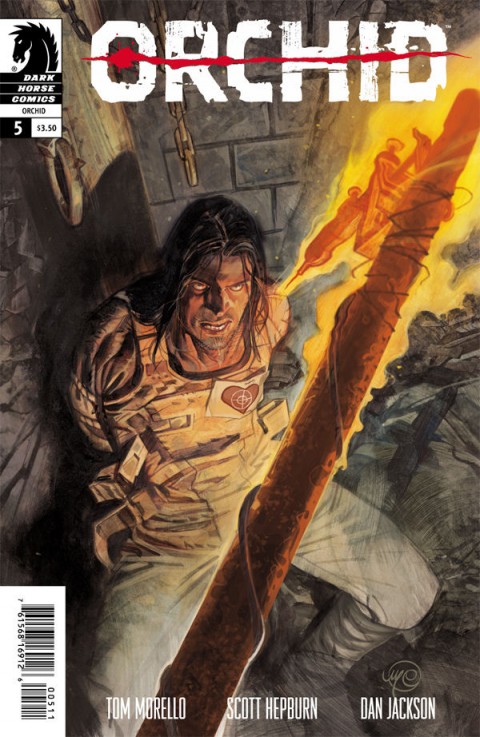

Writer: Tom Morello

Artist: Scott Hepburn

Colourist: Dan Jackson

Letterer: Nate Piekos

Cover: Massimo Carnevale

Publisher: Dark Horse Comics

Books such as the revered Ex Machina series by Brian K. Vaughan and more recently Brian Bendis’ Scarlet immediately spring to mind when considering series which are overtly political in their tone. The series have a distinct message to communicate to its readership whether as a commentary of the contemporary political arena or as a mobilizing rallying call against corruption. For well over 20 years, Tom Morello has presented his politics both as a member of rock bands Rage Against the Machine and Audioslave, as well through his work as a solo artist. Last year Morello turned his attentions towards comic books as an avenue to explore his political side, scripting what would become Dark Horse’s 12-issue maxi-series, Orchid.

The series, Morello’s first foray into the craft, is set within a post-apocalyptic dystopian world where the wealthier echelon of society exploits the lower economic classes, leaving them to scrape by and survive (all too literally) in the wild. The story itself is a tale about a young prostitute named Orchid who, like her social circle, is branded with the tattoos “property” across her chest and “know your role” across her forearms. Beginning as more of an isolated individual caring only for her mother and brother, their deaths hasten her hatred for the societal powers, unexpectedly driving her towards the tutelage of an old revolutionary named Opal. Joining together with a young rebel named Simon, the three trek across the land in search of the rebels’ leader Anzio who had previously been captured.

Issue five picks up with the trio preparing to lay siege to Fortress Penuel with the intent of rescuing Anzio. Using a barely covered yet topless Orchid as bait, Simon rides in to knock two would-be sexual assaulters to the ground, executing the first phase of Opal’s plan to enter the fortress. The pages early in the issue work in contrast to Orchid’s former calling, using her sexuality to the advantage of the trio’s cause; it feels like an empowering act comparatively to her past subjugation at the hands of her pimp. The story takes a slight comedic turn as the socially awkward and bashful Simon implores Orchid to put her shirt back on. This return to the town also depicts a measure of closure for Orchid as she comes face to face with her former pimp and his cohorts for the first time since the death of her mother. In a vain attempt to impose his will and perceived social dominance, he has some choice words for Orchid, comments which prompts Opal to quickly behead two of the pimp’s henchmen with her sword before slicing off his genitals and forcing them down his throat. The act functions as a significant turn for Orchid, whom thanks Opal for freeing her from his clutches. In response, Opal replies that Orchid was free the moment she decided to defy him. Morello summarizes the political message of his work here, indicating freedom of self to be evident at first action in revolt against an antagonism.

His politics come to the fore once more towards the middle of the issue during Opal’s monologue about the rise of a conscious people and their inherent invincibility against oppression; we additionally find Morello trying to convey a philosophical message. He writes that in order to win a war, one must first conquer themselves. He then adds that Orchid’s danger stems from the reality that her passion is born from anger, while Morello writes rebellion stems from love. He concludes his narrative with two points, writing that two mistakes one can make are “not going all the way,” and “not starting at all.” His politics are ripe throughout the book, which despite functioning as the heart of the work, also detracts from the total experience of the story. The storytelling itself, although strong and competent, is over-powered by Morello’s narrative voice, a trend strung throughout the opening five issues. As each panel is read, Morello’s distinct voice takes precedence rather than that of the characters themselves. This is less the case throughout the actual dialogue between the characters, however the characters feel as though they lack defining personality traits. Morello’s writing is strong considering his dearth of previous experience, and although the book is enjoyable, it’s not hard to imagine a reader feeling as though they’re being clubbed over the head with Morello’s point of view.

Canadian artist Scott Hepburn helms the book’s artistic duties and turns in some fantastic work to complement Morello’s story. Hepburn hits his mark in this issue, notably during the town square two-page spread in the early pages featuring Orchid’s latest encounter with her former pimp, a meeting which results in some of the most outright gruesome artwork in comics. He completes the work with finesse, artfully piecing together fantastic beheadings, stabbings and an act that would make all males squeamish. In some of the book’s later pages, we find the trio of travellers with their new companions for hire attempting to avoid the beasts and the “bridge dwellers” living on the fringes of civilization. In one panel where they narrowly avoid detection, we find the trackers further off in the background, while Orchid and her companions are in the foreground; the treat here however is the angling of Hepburn’s pencils which puts the two parties on a diagonal from each other creating tremendous environmental depth on the page. Hepburn’s landscapes later in the issue are nicely drawn as well, enhanced by the perfectly suitable talents of colourist Dan Jackson who is as equally skilled at colouring the inherent violence the book presents as he is colouring the beauty of a moutainside.

Orchid is a deeply political story, one which evokes strong emotions from its characters and attempts to encourage similar emotions from its readers. However, the politics of the book and of Morello overwhelm the plot and its characters leading to the book being perhaps over-politicized. The world these characters reside in is designed to reflect the political conditions of contemporary society, characters which are in turn used to convey the principle of arousing class consciousness among the poorer economic classes. It’s here where Morello’s work could lose readers. Orchid is not an accessible book by any means, rooting itself in the politics of the writer and left-wing symbolism such as the mask worn by General China which has a red star stitched into it. References to the star or class consciousness may be misunderstood in the absence of context, while the story feels heavy-handed in its presentation. The book is quite good and could stand on its own merits, but you shouldn’t require a background in political science to understand a comic book.